Just how big is the funding shortfall faced by Social Security? What is the cost of delay in implementing a solution? The magnitude of the problem can be quantified in two ways: 1) the funds required each year in addition to projected payroll tax revenues, or 2) the present value of the total additional funding required in all future years.

By either measure, the system currently needs reform and the sooner changes are enacted the better.

Annual Funding Requirements. Social Security has collected surplus revenues since the last major reform in 1983. However, the money itself was spent on other federal programs and debt reduction, and was credited to the Trust Fund in the form of special government bonds.

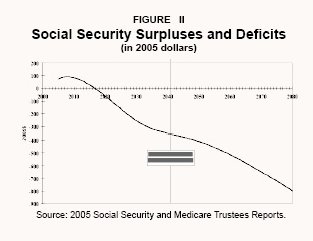

Social Security is expected to collect more revenues than it pays out in benefits until 2016. Every year after 2016, Social Security will run a deficit, which, at the current tax rate, will grow each year.

What will be the magnitude of these annual claims on federal resources? The largest source of general revenue for the federal government is personal and corporate income taxes. Thus, a natural way to quantify the Trust Fund's claims on general revenues is in terms of federal income tax revenues.

Prior to the Trust Fund's exhaustion in 2041, Social Security will make growing claims on Treasury funds:

- The largest previous transfer from the rest of the budget to Social Security amounted to 4.55 percent of federal income taxes in 1982, prior to the last major reforms in 1983.

- By 2022 – when only about half of the baby boomers born between 1945 and 1964 will have reached retirement age – the transfers are projected to be about 5.5 percent of income taxes, higher than any previous transfers.

- In 2041 alone, Social Security will claim $355 billion from the Treasury – 14.3 percent of federal income taxes.

If the past is any indication, Congress will likely reform the program in some way well before 2041. The drain on federal revenues begins in 2017 and, more importantly, Medicare will also impose mounting pressures on the budget in coming years. Thus it is unlikely that Congress will even wait until 2022 to make reforms.

Social Security's Unfunded Obligations. Social Security's financial position can also be expressed using a single number to represent all the annual shortfalls in future years. Historically, the Social Security Trustees have used 75-year projections to determine the funding required to meet the program's future obligations. The 75-year projection tallies the present value of scheduled benefit payments minus the present value of scheduled payroll and benefit taxes over the next 75 years, then subtracts the current value of the Trust Fund. The present value of the gap between benefits and taxes is $5.7 trillion; subtracting the Trust Fund balance of $1.7 trillion results in a 75-year unfunded obligation of $4 trillion.

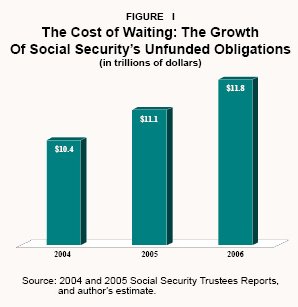

Moreover, at the end of the 75-year horizon there is a growing deficit, which is expected to continue indefinitely. To account for deficits beyond the 75-year window, a longer horizon is needed. One way to do this is to calculate the unfunded obligation into the infinite future. The present value of the gap between scheduled benefits and dedicated taxes in all future years is $12.8 trillion. Offsetting this amount with projected Trust Fund balances yields the $11.1 trillion perpetuity unfunded obligation reported by the Social Security Trustees (see Figure I).

Cost of Delay. But the problem is not the same next year – as with any unpaid debt, we owe more later if we do not pay today. The $11.1 trillion unfunded obligation grows each year at the government borrowing rate. Next year, the unfunded obligation will be $11.8 trillion ($11.1 trillion x 1.06), or $666 billion higher than this year, under identical assumptions and assuming a nominal interest rate of 6 percent.

Trust Fund. The surpluses have been credited to the Trust Fund and are credited interest at the government's borrowing rate. Under current law, the surpluses over the next 12 years will also be credited to the Trust Fund. Unless the law changes, when the Trust Fund's bonds are cashed in at the Treasury, taxes must be raised, programs cut, or funds borrowed, in order to pay promised Social Security benefits. Social Security will redeem the Trust Fund's bonds between 2017 and 2041 for cash from the U.S. Treasury. However, the Treasury must come up with the money. The annual cost of these redemptions is depicted in Figure II.

Social Security's Actuarial Deficit. The payroll tax increase necessary to bring the system into actuarial balance (Social Security's "actuarial deficit") is 3.5 percentof payroll. If the payroll tax rate were permanently increased from 12.4 percent to 15.9 percentnow – and the surpluses and current Trust Fund bonds were invested in stocks or bonds earning the government borrowing rate – the system would be solvent forever. A 3.5 percentage point payroll tax hike is a 28percent tax increase and would collect an additional $166 billion in taxes this year, with the amount growing every year with wages.

However, if we wait to raise the payroll tax rate (and to invest the current Trust Fund balance and future surpluses), the actuarial deficit will rise with time, and the tax increase necessary to close the gap also will rise. Next year, the actuarial deficit will rise from 3.5 percent of payroll to about 3.56 percent. Waiting until 2017 to initiate a reform would result in a 26 percent increase in the actuarial deficit.

Conclusion. So, what is the cost of waiting? Is it the $666 billion change in the size of the unfunded obligation between 2005 and 2006 or is it the growth in the actuarial deficit from 3.5 to 3.56 percent of taxable payroll? Either way we measure the cost of waiting, it is expensive.

By any accounting, Social Security's financing will soon be inadequate. Furthermore, Social Security's financing cannot be viewed in a vacuum. Medicare spending will exceed Social Security spending in 20 years, and its burden on the rest of the federal budget comes sooner. If one of the goals of reform is to reduce the tax burden the next generation must shoulder, then the current generation must make some hard choices today.

Andrew J. Rettenmaier is an NCPA senior fellow and the executive associate director of the Private Enterprise Research Center at Texas A&M University.