Over the last decade, the Social Security Administration has evaluated numerous reform proposals. Recently, when evaluating reforms that involve investments in the stock market, the Social Security Administration assumed the historical average annual real stock return of 6.5 percent will persist into the future. The Social Security Administration also projects the future status of the program. These projections are summarized in the annual Trustees Reports and form the basis for scoring the reform proposals. The most recent Trustees Report assumes the real annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate will be about 1.9 percent over the 75 year horizon. This assumption is lower than the actual experience of the past 75 years, a period in which the economy grew at a real rate of 3.4 percent a year, on average.

Some critics of personal accounts argue that a 6.5 percent stock return is inconsistent with the slower economic growth. Is this criticism valid?

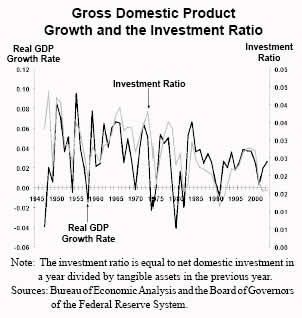

What Determines Economic Growth? Economic growth, as measured by the growth rate of GDP, is fundamentally determined by investment. [See the figure.] Historical data shows a steady decline in net investment as a share of GDP. Net domestic investment averaged more than 10 percent of net national output in the 1960s and 1970s, but declined to 9 percent in the 1980s and 7.4 percent in the 1990s. Based on this trend, it is reasonable to assume that the future GDP growth rate will be lower than in the past. However, slower GDP growth does not mean that stock returns will necessarily be lower.

What Determines Stock Returns? Stock returns vary considerably from year to year and could easily be negative. But in the long run they are fundamentally determined by the rate of return on capital. The return on capital has been relatively stable over time and has been estimated to be concentrated in the range of 7 to 10 percent per year in real terms (after adjusting for inflation). Therefore, relative to this historical return on capital, assuming a 6.5 percent annual rate for long-run stock returns is actually rather conservative.

What Determines the Rate of Return on Capital? The rate of return on capital is the rate required to induce investors to hold the nation's capital stock. This rate differs from country to country because of differences in institutions, which produce different risk premiums. For example, countries that have insecure property rights tend to see low (or even negative) growth rates, and the rate of return on capital tends to be relatively high (because investment in these countries is viewed as very risky). Countries with strong property rights, by contrast, see higher growth rates, and the rate of return on capital tends to be relatively low (because investment in these countries is safer).

The rate of return on capital in the United States is generally set by the world capital market. Since an investment here is an alternative to an investment somewhere else in the world, worldwide investment opportunities determine how much capital earns in the United States. Also, many U.S. corporations are multinational, with investments all over the world. So when one invests in U.S. companies, one is often investing in the world capital market.

The Critique. The critics of personal accounts have, however, taken a different approach. [For a discussion of the critics' concerns, see Dean Baker and Mark Weisbrot, Social Security: The Phony Crisis (The University of Chicago Press, 1999), pp. 88-104.] They note that the return on stocks can be divided into two main components: 1) dividends paid to shareholders and 2) capital gains resulting from increases in the stock price. The dividend-price ratio (the dividend distributed to stockholders divided by the market price per share) has averaged 3.6 percent since 1949. If the dividend-price ratio remains at 3.6 percent, the annual growth rate of stock prices would have to be 2.9 percent in order to produce the overall 6.5 percent return projected by the Trustees.

Assuming that capital earnings are a constant share of GDP, then capital earnings would grow at the same rate as GDP, which is estimated by the Social Security Trustees to be 1.9 percent. However, the critics contend that if the assumed future GDP growth rate is 1.9 percent, then the annual stock price increase would also be 1.9 percent to maintain a constant price-earnings ratio. Combined with an annual 3.6 percent dividend-price ratio, the return on stocks would thus be 5.4 percent. To arrive at a 6.5 percent return under the lower GDP growth assumption, the price-earnings ratio (the market price of a share of stock divided by earnings per share), which is currently about 23:1, would have to rise to 48:1 by 2080, which is considered an implausible outcome.

Thus, the critics say, low rates of projected economic growth are incompatible with a 6.5 percent return on stocks.

Addressing the Critics' Concerns. However, within this framework it is possible to reconcile the critics' paradox in two ways. First, one of their primary assumptions is that the dividend-price ratio will stay at its historical average while GDP growth is assumed to be lower than its historical average. However, since lower projected GDP growth means lower investment, a larger share of earnings will be paid out in the form of dividends. As a result, the dividend-price ratio will rise corresponding to the lower GDP growth.

Second, note that earnings growth is not solely determined domestically. Limiting the extent of earnings growth to domestic GDP growth ignores the international nature of the firms represented in the stock market and the ability of workers to invest in the global economy. Earnings growth of multinational and international firms will reflect international GDP growth, which may well exceed the growth in domestic GDP, particularly if developing countries like China and India are considered in the equation.

Conclusion. Some critics of personal retirement accounts have argued that the projected earnings on stock returns are too high, given the projected GDP growth rate. They suggest that for consistency, the assumed stock return should be lower. A lower return would make reforms that include stock market investments less appealing. The apparent paradox identified by these critics can be reconciled by a higher dividend-price ratio. Also, the earnings growth in the stock market may exceed the domestic GDP growth rate due to the international nature of investment.

Liqun Liu is an associate research scientist with, and Andrew J. Rettenmaier is executive associate director of, the Private Enterprise Research Center at Texas A&M University. Rettenmaier is a senior fellow with the National Center for Policy Analysis.