A citizen who lives in any one state can buy a toaster produced in any other state. The same citizen can also buy a lawnmower, a sofa, an automobile or virtually any other product – regardless of the state where the product is made.

This same freedom does not exist in the market for health insurance, however. Take Texarkana, a city that straddles the Texas-Arkansas border. People who live on the Texas side of the city cannot buy insurance sold to people who live on the Arkansas side and vice versa – even though all Texarkansans can see the same doctors and get treated at the same hospitals.

Laws that keep people who live in one state from buying health insurance sold in other states balkanize the health insurance market and make it less competitive than it could be. As a result, people pay higher prices and have fewer choices than they would have if they could purchase insurance in a national marketplace.

Consumers will get some relief, however, if Congress passes a bill proposed by Rep. John Shadegg (R-Ariz.). It would allow insurers licensed in any one state to sell insurance (under the rules of that state) to individuals and small groups residing in any other state. What difference will the Shadegg bill make?

Avoiding Costly Mandated Benefits. Mandated health insurance benefits are state regulations that require insurers to cover specific services and specific providers. Currently, there are 1,823 state-mandated benefits among the 50 states, and an additional 295 mandates are now being debated in state legislatures.

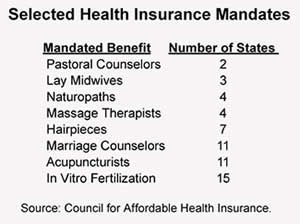

Mandates cover services ranging from acupuncture to in vitro fertilization. They cover providers ranging from chiropractors to naturopaths. They cover bone marrow transplants in New Jersey, hairpieces for chemotherapy patients in Minnesota, marriage counseling in Connecticut and pastoral counseling in Maine.

These laws mean that if people buy insurance at all, they must purchase a bloated and expensive package of benefits designed by politicians. They are forbidden to buy insurance that reflects their own preferences, tailored to individual and family needs. A family of teetotalers is thus forced to buy protection against alcoholism, even though they neither want nor need such protection. A couple well past child bearing years is forced to buy in vitro benefits they do not plan to use. Catholics are forced to buy contraceptive coverage they find morally objectionable.

As the Table shows, 11 states require insurers to cover marriage counselors, four mandate coverage for naturopaths, three cover midwives, 11 cover acupuncturists and four require coverage for massage therapists. Other states have mandated such procedures as in vitro fertilization (15 states), port-wine stain birthmark removal (two states), and treatments for morbid obesity (four states).

Compared to the costs of barebones insurance, these kinds of mandated benefits hike premiums considerably, thus pricing otherwise healthy people out of the market. In fact, studies estimate that as many as one of every four uninsured Americans has been priced out of the health insurance market by mandates.

If mandates do so much harm, then why do they exist? Very few mandates have been enacted because of patient pressure. Almost all are the result of the lobbying power of special interest providers. And once a state-mandated health benefit is enacted, it is almost impossible to get it repealed.

Not all states have been equally bad at limiting consumer choice and raising the cost of insurance. For example, people who live on the Arkansas side of Texarkana bear only 24 mandated benefits; whereas people on the Texas side must live with more than twice as many. Overall, there are as few as 13 mandated benefits in Idaho and as many as 58 in Maryland and 60 in Minnesota. Further, some states exempt small firms (with fewer than 50 employees) from these regulations.

Under the Shadegg bill, Minnesotans, at least in principle, would be able to purchase insurance licensed in Idaho. Of course, Idaho insurers would have to be willing to sell in Minnesota and premiums might not be the same in both states (because of other factors that influence health care costs). Still, the bill would allow Minnesota residents to avoid many of the cost-increasing regulations imposed by the Minnesota legislature.

Avoiding Other Cost-Increasing Regulations. Another problem is the proliferation of state laws that make it increasingly easy for people to obtain insurance after they get sick. Guaranteed issue regulations (requiring insurers to take all comers, regardless of health status) and community-rating regulations (requiring insurers to charge the same premium to all enrollees, regardless of health status) are a free rider's heaven. They encourage everyone to remain uninsured while healthy, confident that they will always be able to obtain insurance once they get sick.

Moreover, as healthy people respond to these incentives by staying uninsured, the premiums required to cover costs for those who remain in insurance pools rise significantly. These higher premiums, in turn, encourage even more healthy people to drop their coverage. In general, all such legislation prevents risk from being accurately priced in the marketplace -that is, people cannot purchase pure insurance against risk; rather, they must purchase a politically designed package of specified medical benefits.

Choosing Consumer Protections. Not all regulation is bad for consumers. For example, consumers have an interest in knowing that their insurer is solvent (that is, can pay the patient's medical bills as they come due). Regulators that oversee solvency requirements, therefore, can perform a valuable service. Additionally, consumers have an interest in making sure that insurance companies play fair (for example, that they don't cancel or raise rates for someone simply because he has the misfortune to get sick). Under the Shadegg bill, consumers will be more likely to get the benefits of these value-enhancing regulations without suffering the cost of value-reducing ones.

Creating A Market for Regulation. What can we expect as a result of the Shadegg bill? Currently we have 50 states with 50 different sets of regulations. If all insurers licensed in each of the 50 states were willing to sell their products in the other 49 states, the typical consumer would have an opportunity to choose among 50 regulatory regimes.

Defenders of mandated benefits and other forms of regulation frequently assert that these are "consumer protections." Insurance companies, on the other hand, deride them as "special interest" legislation whose costs exceed their benefits. The Shadagg bill will allow these competing claims to be put to the market test. Those regulations that enhance the value of insurance (for example, whose benefits exceed their costs) are likely to win out in competition with those that do not.

The law will also help better public policies replace inferior ones. A state that subsidizes risk pools for people who are uninsurable through no fault of their own will leave insurers free to charge lower and fairer prices to the healthy. Insurers in such a state are more likely to compete successfully in a national market than insurers in a state that attempts to help the uninsurable by legislating rules that raise everyone's premiums.

Conclusion. The Shadegg bill promises to usher in a new era in the evolving market for health insurance. Consumers will be able to shop in a national market, as opposed to 50 separate state markets. Regulatory regimes will compete against each other and those that survive will be those that add value to the product. Insurers will be able to offer products that meet individual and family needs without the cost-increasing burden of inefficient regulations.

Jack Strayer is a Washington, D.C., representative of the National Center for Policy Analysis.