Many people displaced by Hurricanes Katrina and Rita are faced with the challenge of finding new housing with few resources and a lack of steady income, at least for now. The federal government spends billions of dollars a year on housing assistance and programs to provide low-cost housing for the poor. However, attempts to house homeless evacuees by expanding these programs would be a big mistake. Specifically, it would drive up demand for all low-income housing without increasing supply. The result: a large government expense with no reduction in need.

Avoiding Command and Control. In an attempt to address supply, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) may purchase up to 300,000 new travel trailers and manufactured houses. It is also creating mobile home parks to house evacuee families. Many politicians fear, and rightfully so, that the encampments will become "FEMA ghettos" that isolate the poor from communities and jobs. The problem is that rather than allowing the market to function, the government is paying too much and sopping up the available supply of RVs and modular homes, which will raise prices to individual buyers.

Enacting Enterprise Programs. A better approach is the NCPA's concept of "enterprise" programs. The idea is similar to "enterprise zones," economically distressed areas exempted from uneconomic regulations. Enterprise programs, however, would not be confined to a geographical area. On the supply side, a producer/seller/entrepreneur qualifies to participate in an enterprise program by providing housing opportunities to poor and distressed families. On the demand side, the program would give low-income families access to non-traditional housing markets with funds currently tied up in government provision.

The private sector has been a powerful and effective provider of affordable housing, and Katrina evacuees would likely benefit from a market-driven approach with a wider variety of choices, including non-traditional housing, sweat equity programs and enterprise programs.

Making Ownership Possible. The Federal Emergency Management Agency has announced an initiative to provide about 2,500 displaced families with vouchers good for three months of rental housing (valued at about $2,358 based on the national fair market value of a two-bedroom apartment), with extensions up to 18 months if needed. The Department of Housing and Urban Development is implementing a similar program for those who were previously receiving HUD assistance. The vouchers can be used anywhere in the country to rent housing in the private market.

However, these programs are limited to rental assistance, and the funds cannot be used to purchase a home. Hurricane Katrina evacuees would be best served by a voucher (based on family size) that could be used for rent, for lease-to-own or even for a down payment on a house. If other restrictions were eliminated (see below), families could have access to a wide array of housing alternatives in the private market.

Increasing Supply Through Manufactured Housing. Custom homes are the most expensive to build. Modular homes built in a factory and assembled on-site cost less than half the price of a site-built home. These less costly homes are almost entirely built in a factory on a permanent frame designed for over-the-road transportation. Modern manufactured homes are also durable, having a life expectancy of 30 to 55 years.

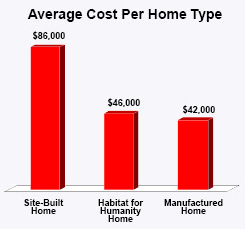

In 2002, manufactured homes accounted for 11 percent (168,000 units) of all new single family housing starts. The average cost to build a new manufactured home was about $42,000, excluding land and financing costs, compared to about $86,000 for a site-built home. Yet in many cities, modular homes have been barred from the market by zoning laws and building codes. However, such regulations are there to protect real estate interests, not consumers. Special interests have succeeded in raising the costs of these services so that the poor have been priced out of the market. So instead of buying housing in the real estate market, too many poor families have to rely on public housing.

Increasing Supply Through Sweat Equity Programs. Another initiative proposed by President Bush for Katrina evacuees is the Urban Homesteading Act, which would allow low-income families to obtain federal property on which to build through a lottery system. In return, families would build on the land with the help of a low-interest mortgage from a charitable organization such as Habitat for Humanity. Such privately run programs have been successful: Since 1976, Habitat has built nearly 200,000 homes. Habitat homes cost an average of $46,600 per unit – about half the per unit cost of a modern public housing unit. Habitat enjoys a foreclosure rate of less than 1 percent, significantly lower than that achieved in government home loan programs.

Habitat succeeds by putting conditions on potential beneficiaries. Would-be homeowners must demonstrate a history of responsible behavior (such as living in a stable family and taking care of property), take part in the construction of their home, and make a very modest down payment and meet a monthly mortgage payment.

Increasing Supply Through Single-Resident-Occupancy (SRO) Hotels. Most of the concern has been about housing displaced families, but many of the displaced are singles. SROs could provide these individuals with another source of inexpensive housing. They are typically very modest (single rooms with a bed, a small refrigerator, and a microwave) but are available to low-income renters without the usual barriers. Most do not require a security deposit, a background or credit check, or a deposit of the last month's rent.

"Cost-increasing regulations have priced poor families out of the market for private housing."

Most of the nation's SROs were demolished by urban renewal programs of the 1970s and 1980s, while local zoning laws and building codes prevented new ones from being built. Today, some cities have begun to cut red tape on SRO construction. We should encourage all cities in affected states to repeal local regulations that prevent the construction of SROs.

Conclusion. Housing considerations for hurricane evacuees should take into account long-term prospects for housing, not just government-dependent quick fixes. Manufactured homes, sweat equity mortgages, and SROs can increase the housing supply, but local zoning laws often restrict non-traditional housing. The federal government could require states to accommodate enterprise programs in return for reimbursement of hurricane-related expenditures.

Joe Barnett is director of publications and Pamela Villarreal is a research associate with the National Center for Policy Analysis.