Indiana Gov. Mitch Daniels has signed an agreement to outsource the administration of health, welfare and nutrition programs to a consortium led by the IBM Corporation and Affiliated Computer Services, Inc. Under the 10-year contract, these companies will receive and process applications for benefits received by one in six Indiana residents and provide technological support to the state's Family and Social Services Administration (FSSA).

The use of private contractors to administer government programs is controversial. However, experts believe that properly administered privatization programs can improve services and lower costs.

The Current System Is Inefficient. Like many other states, Indiana's social services have been bureaucratic and fragmented. As a result, they are not convenient for the state's welfare recipients and are costly to operate. Under the state's traditional system:

- Clients must apply for each social service in person at a state office during business hours, and each visit requires an average wait of two to three hours.

- In almost three out of four cases (72 percent), eligibility is not determined during the initial interview — requiring additional verification and often additional office visits.

- Almost every action in the eligibility process requires a different form and/or notice, and each of the state's 94 counties has had its own set of procedures.

A client's assigned caseworker is generally the only person who can handle his or her case, since records are kept manually and each caseworker holds the files on their clients. Caseworkers can only serve clients face-to-face and resolving problems often requires multiple trips.

The Current System Is Ineffective and Wasteful. The 1996 federal welfare reforms implemented a new cash assistance program, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), that time-limited benefits and required states to move clients to work. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Indiana has the worst welfare-to-work record in the country. Caseloads nationwide dropped an average of 58 percent from August 1996 to December 2005, but Indiana's caseload fell only 6.3 percent. In 1996, 51,437 Hoosier families received cash welfare benefits; in 2007, the number was still high at 48,213.

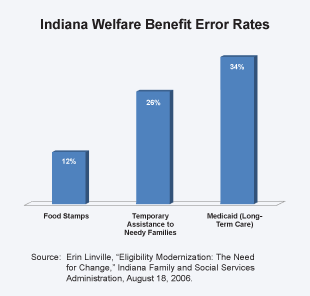

Furthermore, Indiana's existing system for administering welfare, Medicaid and food stamps has a high rate of errors in approving applicants who do not qualify, and/or providing too little or too much assistance to those who do qualify. As the figure shows:

- Thirty-five percent of eligibility determinations for Medicaid long-term care in 2003 contained errors, costing Indiana taxpayers an estimated $10 million to $50 million per year — and the federal government up to $100 million annually.

- Twenty-six percent of TANF benefit determinations contained errors.

- Twelve percent of food stamp benefit determinations were in error — and Indiana ranks 48th among the states in recouping food stamp overpayments.

Extending benefits to ineligible people costs Indiana taxpayers $100 million a year, not counting fraud. Furthermore, since TANF and food stamps are primarily funded by the federal government, taxpayers nationwide bear additional costs for Indiana's errors.

Features of the New System. In October 2007, Indiana began testing a new social services administrative system using private contractors in 12 counties. The new system will be implemented in the rest of the state in 2008.

The new system allows applicants to apply over the phone or at a Web site at any time of day and on weekends. Automated telephone services will walk callers through a menu of options, or, if callers prefer, connect them with a person who can answer their questions. Applicants can also use an interactive Web site that will ask them about their households, assets and needs, show the benefits for which they appear eligible and even fill out applications that can then be printed, signed and returned.

However, the state and private contractors will maintain offices in all 92 counties where clients can apply for all aid programs at one office. Indiana is privatizing intake and screening, but state employees will continue to provide case work. However, under the new system, records will be kept electronically and clients can talk to any caseworker, not just the ones they've worked with in the past. Caseworkers will be freed from time-consuming paperwork to deal directly with clients. The system will place greater emphasis on moving clients to self-sufficiency.

Successful streamlining efforts place a premium on retaining experienced staff who understand the rules and regulations. IBM offered employment to all existing state employees. Some 1,500 state workers went to work for IBM and ACS. Others will be employed by the state in other positions. The private contractors will build a call center and eligibility processing center in Marion, Ind., in addition to opening local offices. Incoming mail from applicants will be processed at the center, where documents such as birth certificates and utility bills will be converted into electronic client files.

In addition to their expertise in technology, the contractors will provide the capital to develop, install and maintain new computer hardware and software systems.

Expected Results and Economic Benefits. State officials expect to improve the timeliness of processing benefit applications. Furthermore, the new system is expected to help the state meet the new federal requirement that 50 percent of TANF recipients work or be engaged in job-related activities, such as job training or searching for a job, at least 30 hours a week. If this goal isn't reached, the state will face fines of over $10 million.

In terms of economic efficiency, officials say the $1.16 billion contract will result in $500 million in administrative savings over a decade. Additional substantial savings will occur as errors and fraud are reduced.

Initiatives in Other States. Many states are trying to deliver social services in new ways. According to the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), an investigative arm of Congress:

- Twenty-six states have either implemented or are developing systems to allow online applications for at least some benefits.

- Half of states are either using or developing call centers, which allow people to inquire about and apply for benefits by phone.

- Several states are using mass mailings, holding community meetings and disseminating information through community organizations to encourage welfare service clients to use alternative application processes.

Steps to increase the efficiency of services or contract out service delivery to private firms have met with resistance from public employees. There are reasons to be skeptical. Last year, Texas ended an ambitious privatization contract for welfare services with the global consulting firm Accenture.

In Texas, the contractor was beset with complaints of delays in enrollment and problems getting applications processed. Experts attribute the program's failure to undeveloped technology, unrealistic timelines, and untrained and inexperienced staff.

Texas is still struggling with slow processing times for social service benefits and overburdened phone lines. However, the failure in Texas offers many lessons to state social service reformers. These lessons are being taken to heart in the new Indiana plan.

Heidi Sommer is an intern at the National Center for Policy Analysis.