The disability insurance component of the U.S. Social Security system is funded by a 1.8 percent payroll tax. It pays benefits to disabled adults who have earned a required number of credits based on previous years of work. The benefit amount is based on the wages taxed for Social Security. Most people do not realize that the system penalizes those who leave the workforce for a few years. The system often penalizes women, who are more likely to move in and out of the workforce.

How Workers Earn Disability Benefits. In 2007, workers earned one disability credit for each quarter of the year in which they received at least $1,000 in taxable wages or self-employment earnings. The minimum amount of wages needed for one credit increases annually with the rise in average pay. Thus, in 2008, workers will receive one credit for every quarter in which they earn at least $1,050 in wages.

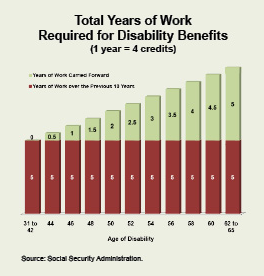

Workers can only earn 4 credits per year, and the minimum number of credits required rises with age. Thus, a 21-to-23-year-old worker needs only six credits, whereas a 27 year old must have 12 credits. Furthermore, older workers must have earned most of their credits within the recent past. For instance [see the figure]:

- A 31-year-old disabled worker can claim benefits if he or she has earned at least 20 credits since age 21.

- However, a 50-year-old worker must have 28 credits, 20 of which must have been earned in the 10 years immediately preceding the disability.

- Finally, a 62-year-old worker must earn 40 credits (the maximum required) — 20 in the 10 preceding years.

Eligibility for Social Security disability is all or nothing. There are no benefits for partial disability or partial benefits for a disabled worker who does not have the requisite number of credits. Disabled workers who do not have enough credits may be eligible for another program, Supplemental Security Income, but to qualify they cannot have more than $2,000 in assets ($3,000 per couple). Workers who become disabled at age 62 or older can claim early (reduced) retirement benefits.

Losing Disability Credits. Since eligibility is based on having earned credits in the years immediately before a worker becomes disabled, an individual who earned credits 20 years ago may find that not all of them count. For example, consider the case of a 42-year-old woman who worked full-time from age 21 to 31 and thus earned 40 credits. She has twice the number of credits required to receive benefits if she becomes disabled at age 32. However, if this woman exits the workforce at 32 to raise young children or attend school full-time:

- When she re-enters the job market as a full-time worker at, say, age 42, she has no qualifying credits, and will not receive benefits if she becomes disabled.

- As she ages, the bar becomes higher; thus, if she re-enters the workforce at 44, because she is older she would need 22 credits, meaning she would have to work at least 5 years more before regaining her eligibility.

- Any additional credits she needs can be drawn from the earlier years she worked, but the requirement for 20 credits in the 10 previous years does not change.

Furthermore, a woman entering the workforce for the first time as an older adult — as the result of a divorce, for instance — has to earn all her required credits in the current 10 year period. Thus, a 44-year-old woman who had not previously earned credits would not be eligible for disability until age 52.

A Private Alternative to Social Security Disability. In contrast to the United States, workers in Chile have individual accounts as part of the privatized Social Security system. Instead of payroll taxes, workers make deposits to accounts that are individually owned and invested in private equities. Because their benefits are funded from their accounts, workers do not lose any benefits if they cease to work, and their account balances continue to accumulate interest after they stop making contributions. If workers do not draw on their accounts for disability benefits, the funds continue to earn dividends and interest until the workers use the money for retirement benefits.

What would happen to the 42-year-old American worker in the previous example if both the employer and employee disability taxes were instead deposited into an individual disability account?

Assuming the woman began working full time at age 21, in 1985, with a salary of $30,000, and received a 3 percent annual increase in nominal pay, by 1995 she was earning $40,317. During that period, the combined employer-employee Social Security payroll (FICA) tax for disability increased from 1 percent to 1.88 percent, and her disability coverage cost a total of $4,872. If these funds had been put in a disability account:

- In 1985, the $300 paid into the disability system would go to a private account at a contribution rate of $25 a month.

- Assuming the money earned an average annual rate of return of 10.87 percent (the actual return of the S&P 500 stock index from 1985 to 2006), the worker would have about $26,000 by the time she returned to the workforce.

- With the accrued amount in her private account, she would have enough to purchase a long-term disability insurance policy through her employer, if one were offered, or in the private market.

These figures assume the private account continued to accumulate interest during the years she made no contribution, from 1996 to 2005.

Private Disability Insurance. Private disability insurance policies come in a variety of shapes and sizes. Monthly premiums vary based on the features of the policy. Some policies supplement public disability payments. Policies that have higher annual premiums than the annual amount paid for Social Security disability generally pay a higher percentage of a worker's salary (up to 80 percent) than Social Security disability, and cover a worker up to age 65 (although some policies are for shorter periods). Some policies are based on a worker's ability to perform the specific job he or she is trained to do. For example, a surgeon may be unable to perform surgery and must instead take a desk job, but could still qualify for private disability benefits.

To qualify for Social Security disability, on the other hand, a worker must be unable to perform any type of work. Because of this stipulation, it is more difficult to qualify for Social Security disability than it is for private disability insurance.

Conclusion. Under the current system, those who exit the workforce with the intention of re-entering it after some time risk losing their disability benefits. This may affect women to a greater degree because they often leave the workforce to care for children or pursue higher education. Private accounts for disability benefits would allow workers to provide their own benefits. This would also ensure that workers do not contribute to a system that may not support them if they become disabled.

Pamela Villarreal is a policy analyst and Alan Lin is an intern with the National Center for Policy Analysis.