The popularity of 401(k) plans has grown in recent years. According to the Employee Benefits Research Institute, almost two-thirds of employers offer such plans and millions of employees now contribute to them. These defined contribution plans allow workers to set aside part of their earnings in tax-deferred retirement accounts that are invested in stock and bond funds. A worker can begin to withdraw funds from the account without penalty at age 59 and one-half. All contributions, as well as accumulated dividends and interest, are subject to income tax when the funds are withdrawn.

Federal law allows companies to create 401(k) plans in which workers can borrow against their account balances; about 85 percent of plans have such provisions. An increasing number of account-holders are exercising this option as their balances rise. The average size of 401(k) accounts increased from $37,323 in 1996 to $61,346 in 2006. But many account-holders do not realize how much retirement savings they forgo when they borrow from their 401(k).

How Borrowing Against a 401(k) Works. Borrowing provisions vary among plans; many allow participants to borrow for almost any reason, whether to pay off credit card debt or make a down payment on a home. Plans with loan provisions generally allow an employee to borrow up to half of a vested account balance, but not more than $50,000. Federal law requires that the borrower be charged a “reasonable rate” of interest, which is normally fixed at the prime rate (what banks offer their best customers) plus 1 percentage point. In addition, some plan administrators charge a small fee. The loan must be repaid within five years, or 15 years if it is for the first-time purchase of a home.

The account-holder is both lender and borrower. All loan payments, including interest, are credited to the borrower's 401(k) account and deducted from his paycheck.

Advantages of Borrowing. The most obvious advantage of borrowing against a 401(k) plan is convenience:

Advantages of Borrowing. The most obvious advantage of borrowing against a 401(k) plan is convenience:

- Borrowers need only complete a short loan application, in some cases online or via telephone.

- No credit checks are required.

- In many cases there are no restrictions on the purpose of the loan.

Some plans allow employees to allocate part of their 401(k) balance to a high-yield money-market account and then withdraw the funds as a loan using a debit card. Additionally, the interest rate on the loan is typically lower than what an employee could obtain with a traditional bank loan.

The Opportunity Cost of Borrowing. The primary disadvantage of taking a 401(k) loan is the loss of compound interest and dividends that would have accrued if the money had not been borrowed. Moreover, the interest paid back into the account is unlikely to equal the interest earned by 401(k) investments.

“A $30,000 loan could cost a worker more than $600,000 in retirement income!”

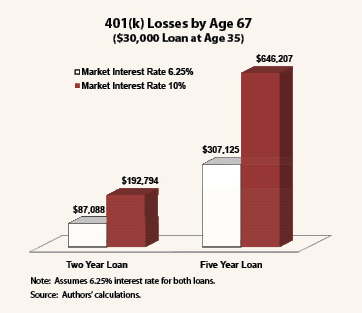

Consider what happens when a 35-year-old worker with a 401(k) account balance of $60,000 borrows $30,000 at an interest rate of 6.25 percent to be paid back over two years. Assume the worker normally contributes $500 a month to the account but cannot do so during the loan repayment period, either because the plan doesn't allow it or he cannot afford it. Instead, he makes after-tax monthly loan payments of $1,333 (including interest). As the figure shows:

- If the account were earning a market interest rate of 6.25 percent, the same as the loan interest rate, he would have more than $87,000 less at retirement (age 67) than if he had not borrowed.

- If the account were earning a market interest rate of 10 percent, he would have more than $307,000 less at retirement than if he had not borrowed.

Next, consider a scenario in which a worker borrows $30,000 over a five-year period, with monthly payments of $583. Assuming no pretax contributions are made during the loan repayment period: - If the account were earning a market interest rate of 6.25 percent, he would have $192,794 less at retirement (age 67) than if he had not borrowed.

- If his account were earning a market interest rate of 10 percent, he would have more than $646,200 less at retirement than if he had not borrowed!

Furthermore, if the worker had allowed the account to grow loan-free at 10 percent and had purchased an annuity upon retirement he would have an annual income of $158,000 for 30 years (until age 97). Borrowing for a five-year period reduces his annuitized annual income to $122,000. A one-time $30,000 loan costs the borrower more than $30,000 a year in retirement income for the rest of his life!

The Penalties for Default. In addition to the opportunity cost of borrowing, the consequences of defaulting on a 401(k) loan can be severe:

- If the borrower fails to repay the loan, the entire principal amount will be subject to both federal and state income taxes.

- If the borrower is younger than 59 and one-half years, the defaulted loan is counted as an early withdrawal, subjecting the borrower to a penalty of 10 percent on the entire principal amount.

- If the borrower quits working or changes jobs, the remaining loan balance must be paid back quickly (usually within 60 to 90 days) or the loan is considered to be in default.

While the loan itself is not taxed, payments on the loan are deducted from the worker's paycheck after taxes. Thus, a worker must use a greater portion of his income to repay a loan than if the same amount of money were a tax-deferred contribution. For example, someone in the 15 percent tax bracket would need to earn about $12,265 in pretax dollars to pay off a $10,000 loan, not including interest and administrative fees. Often the high cost of repaying a loan will cause the employee to stop making regular 401(k) contributions. And some plans do not allow tax-deferred contributions to the 401(k) until the loan is repaid.

Conclusion. The option of borrowing against a 401(k) is attractive; however, potential borrowers should be wary. Even in extreme situations, it is best for workers to seek other sources of capital before tapping their 401(k) accounts. Otherwise, borrowers are leaving much of their potential earnings on the table. A small loan now can equal a huge loss in future retirement security.

Robert Reeves is a research assistant and Pamela Villarreal is a policy analyst with the National Center for Policy Analysis.