The United States has refused to ratify the 1997 Kyoto Protocol intended to limit and eventually reduce emissions of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. The treaty did not meet two requirements Congress deemed necessary for a worthwhile international climate change policy — that it: 1) do no harm to the U.S. economy and 2) include developing nations in emissions regulation. Congress should apply these criteria to proposed domestic climate change legislation.

Bills recently introduced in Congress would control emissions through cap-and-trade schemes. They would place an upper limit, or cap, on the overall level of greenhouse gas emissions, and then distribute or sell to companies or industries emissions credits — rights to emit specific amounts of greenhouse gases. The credits could then be sold in a greenhouse gas market. Companies capable of cutting emissions relatively cheaply or making deeper emission reductions than required could sell their excess emission allowances to companies unable to meet their goals. The idea is that industries would find the most efficient ways to reach the desired reductions. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) says the market value of emissions allowances (in 2007 dollars) could reach $50 billion to $300 billion per year by 2020, depending on the scheme adopted.

However, the cap-and-trade proposals unveiled so far would harm the U.S. economy, disproportionately hurt the poor and fail to produce the environmental benefits promised by proponents.

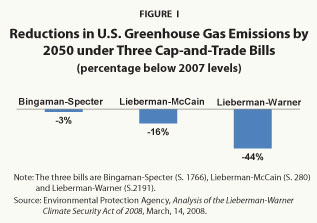

Economic Costs of Climate Change Legislation. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recently analyzed the three most prominent cap-and-trade Senate bills. The EPA found any of the three would reduce U.S. greenhouse gas emissions below current levels. For instance, using 2007 CO 2 emissions levels as a reference, by 2050 [see Figure I]:

Economic Costs of Climate Change Legislation. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recently analyzed the three most prominent cap-and-trade Senate bills. The EPA found any of the three would reduce U.S. greenhouse gas emissions below current levels. For instance, using 2007 CO 2 emissions levels as a reference, by 2050 [see Figure I]:

- Legislation sponsored by Senators Jeff Bingaman (D-N.M.) and Arlen Specter (R-Pa.) would trim U.S. emissions by less than 4 percent below current levels.

- A more stringent bill by Senators Joe Lieberman (I-Conn.) and John McCain (R-Ariz.), would reduce U.S. emissions nearly 16 percent.

- One of the most restrictive bills, introduced by Senators Joe Lieberman and John Warner (R-Va.), would cut emissions 44 percent.

Unfortunately, these bills would substantially raise energy prices and reduce economic growth.

Higher Energy Prices. The greatest impact of the cap-and-trade bills on consumers would be higher electricity and gasoline prices.

- An analysis from Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC) concludes Lieberman-Warner would increase gasoline prices 60 percent to 144 percent by 2030, and raise electricity prices 77 percent to 129 percent.

- The EPA estimates Lieberman-Warner would increase gasoline prices $0.53 per gallon in 2030 and $1.40 in 2050.

Economic Losses. The total economic cost of emissions reductions would rise over time. For example, the SAIC study found that Lieberman-Warner would reduce gross domestic product (GDP) in 2020 by 0.8 percent to 1.1 percent.

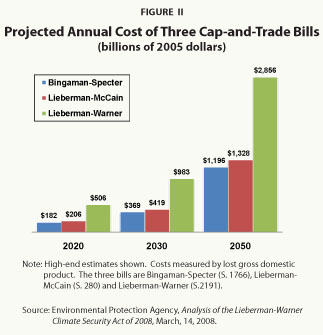

The EPA also compared the economic costs of the three Senate bills. As Figure II shows, by 2050, Bingaman-Specter could cost as much as $1.2 trillion annually (in 2005 dollars) in lost GDP; Lieberman-McCain could cost over $1.3 trillion and Lieberman-Warner could cost nearly three trillion dollars annually!

Lower Living Standards for the Poor. Increased energy prices hit the poorest Americans hardest, making regulations to restrict greenhouse gases highly regressive. Energy costs already consume 15 percent of the poorest households' income, compared to only 3 percent for average households. The CBO estimates that if emissions of CO 2 (the leading greenhouse gas) were cut 15 percent by 2010 through cap and trade, it would reduce the disposable income of the poor an additional 3.3 percent, compared to a 1.7 percent drop for the richest Americans.

Lower Living Standards for the Poor. Increased energy prices hit the poorest Americans hardest, making regulations to restrict greenhouse gases highly regressive. Energy costs already consume 15 percent of the poorest households' income, compared to only 3 percent for average households. The CBO estimates that if emissions of CO 2 (the leading greenhouse gas) were cut 15 percent by 2010 through cap and trade, it would reduce the disposable income of the poor an additional 3.3 percent, compared to a 1.7 percent drop for the richest Americans.

Ineffective Climate Change Legislation. Advocates of cap and trade argue that avoiding the cumulative environmental impacts of climate change — including higher sea levels, more powerful hurricanes and the spread of tropical diseases — far outweigh almost any economic costs. However, there is little reason to believe the emission reductions called for in these bills will stop or even substantially slow global warming. Thus, they will not prevent the harms warming is predicted to exacerbate.

For instance, research from the National Center for Atmospheric Research reveals that even if all the signatories of the Kyoto treaty met emissions targets by 2012, global temperatures would still be only 0.07 to 0.19 degrees Celsius cooler in 2100 than without Kyoto. This would not be enough to avoid the two to six degree increase in average global temperatures some scientists claim will irreparably harm the environment.

Of the three bills discussed above, only Lieberman-Warner would provide more emission reductions than those required of the United States under Kyoto — the others would fall far short. Yet, even Lieberman-Warner would be ineffective because it is unilateral. Developing countries — such as China, India, South Korea, Brazil and Indonesia — are exempt from current international climate change agreements and would not be covered by domestic legislation. Even if all developed countries stopped using energy entirely, there would be little impact on overall greenhouse gas emissions or atmospheric concentrations. Why? Because fast-growing developing countries are expected to account for 85 percent of emissions growth in the next two decades. China has already passed the United States as the world's largest CO 2 emitter and its economic growth rate is more than three times greater.

The EPA's own analysis indicates that just to significantly slow emissions growth (not even stabilize emissions), the United States would have to meet its emission reduction targets under Lieberman-Warner, other developed countries bound by Kyoto would have to slash their emissions by more than 50 percent below their 1990 levels, and developing countries would have to cut their emissions to 2000 levels by 2035.

Conclusion. The benefit promised by recently proposed cap-and-trade schemes — lower global temperature — is unlikely to materialize because they don't include developing nations. Moreover, every economic analysis to date indicates domestic legislation proposed to regulate greenhouse gas emissions will harm the U.S. economy and the most vulnerable in our society — the poor. Lawmakers should not adopt laws that sacrifice the economic well-being of those living in the United States for nonexistent environmental gains.

H. Sterling Burnett is a senior fellow and D. Sean Shurtleff is a graduate student fellow with the National Center for Policy Analysis.