Capitalism and democracy are both known to improve the well-being of women. But which is more important? The social welfare of both men and women can be measured by health, education and employment, and the well-being of women in particular by gender-specific indicators, such as control of fertility. Poor countries generally rank lower than developed countries on all these social metrics, but they can implement public policies to improve conditions. Two major strategies have been tried: 1) market-oriented economic reforms and 2) democratic political reforms. The evidence suggests that institutional reforms that move an economy closer to capitalism have a greater positive influence on the well-being of women than political reforms that increase women's participation in decision-making.

Measuring Sticks and Outcomes. A capitalistic, or economically free, society is one in which institutions are characterized by personal choice, voluntary exchange, freedom to compete and protection of person and property. It requires such public policies as open markets, limited government, stable monetary growth, free trade and a strong rule of law. Several indices exist for measuring the economic freedom of a society. One of the most popular is the Fraser Institute's Economic Freedom Index (EFI). It uses objective data to rate more than 120 countries, from 1975 to the present. Academic studies have shown that a country's economic freedom has positive effects on many measures of economic progress, including investment, growth and income.

Freedom House produces a political rights index (PRI), based on their Freedom of the World survey. The PRI aggregates several factors related to political rights on a single scale, including the right to organize political parties, the significance of the opposition vote, and the realistic possibility of the opposition increasing its support or gaining power through elections. Studies have found mixed support for positive effects of political freedom on measures of human welfare.

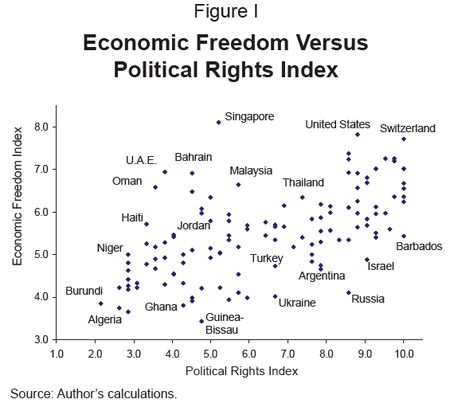

There are large discrepancies among countries in economic and political freedom scores as averaged over the last two decades [see Figure I]. The United States and Switzerland have relatively high levels of both economic freedoms and political rights, while Algeria and Burundi have relatively low levels of both types. On the other hand, Singapore and Bahrain have relatively higher levels of economic freedoms while allowing relatively fewer political rights. Argentina and Russia, until recently, had granted relatively more political rights while allowing relatively limited economic freedom.

Focusing on Specific Outcomes for Women. In order to determine the effects of economic freedom and political rights on women in particular, both the EFI and PRI were evaluated with respect to four outcomes: life expectancy, literacy rates, secondary education enrollment and labor force participation. In addition, many development studies point to the ability to determine family size and control the incidence of pregnancy as important aspects of the quality of life for women. Thus, fertility and use of contraceptives were also measured.

Where applicable, the outcomes were analyzed twice, once for the benefits of each freedom to women in an absolute sense, and once for the benefits women receive relative to the benefits to men. (Contraception use and fertility were only measured absolutely and secondary school enrollment and labor force participation were only measured relative to men.) All of these results were calculated after controlling for cross-country differences in per capita income.

In countries with comparatively high levels of both economic and political freedom:

- A one-point increase in a country's EFI score raises women's life expectancy by 1.2 years.

- A one-point increase in a country's EFI score raises women's literacy rate 3.9 percent.

- When compared to males, a one-point increase in a country's EFI score raises the proportion of female secondary school students by 2.4 percent, but has no significant effect on the labor force ratio.

Unlike the EFI scores, however, changes in PRI scores did not have a significant effect on any of the measures of well-being, with the exception of the female/male secondary school student ratio, where a one-point PRI increase raised the ratio 0.6 percent.

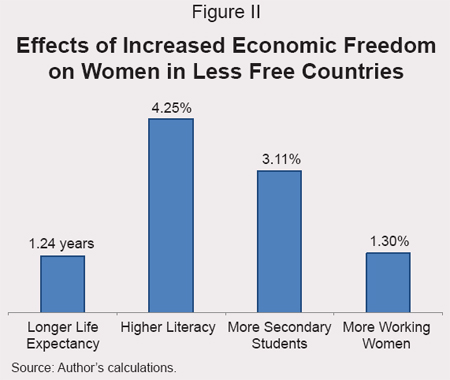

In countries with comparatively low levels of both economic and political freedom [see Figure II]:

- A one-point increase in a less-free country's EFI score raises women's life expectancy by 1.2 years (the same as in economically and politically freer countries), but an increase in the PRI score has no statistically significant effect.

- A one-point increase in a less-free country's EFI score has a greater effect on the literacy rate among women than it does in freer countries, increasing women's literacy 4.25 percent; but again the PRI score is not significant.

- In comparison to males, a one-point increase in a less-free country's EFI score raises the proportion of female secondary school students by 3.1 percent and the proportion of females in the labor force 1.3 percent.

For these countries, the only significant effect of the PRI score was that a one-point increase in political rights reduced fertility rates by 0.03 children and increased contraceptive use by 0.50 percent.

Conclusion. Economic freedom benefits women in additional ways. For example, multinational corporations competing for dependable, productive labor in developing countries implement nondiscrimination policies and training programs, on-site child care and other family-friendly policies that increase work opportunities for women.

Thus, contrary to the claims of some development economists, capitalism yields more than just greater economic efficiency. It also improves the well-being of women. The evidence implies that those societies that rely more heavily upon economic freedoms to promote women's well-being will be more successful than those societies that rely more heavily upon greater political rights to achieve social progress.

Conversely, if a country's government concentrates its efforts on increasing the efficacy of democratic policies in society, rather than on promoting greater economic freedom, it will likely produce smaller improvements in the quality of life for women. Additionally, it might be that governments pushing more political freedom — at the expense of economic freedom — are not quite as capable of generating public policies that effectively supply public goods and encourage social progress.

Michael D. Stroup is a professor of economics and associate dean of the Nelson Rusche College of Business at Stephen F. Austin State University.