The marriage penalty is a quirk in the tax code that pushes married couples into a higher tax bracket than two unmarried single earners living together and earning the same combined income. The 2001 Bush tax cuts all but eliminated the marriage penalty by lowering tax rates and simplifying other elements of the tax code. However, these Bush tax cuts expire in 2010, and American families face steep marginal tax increases if Congress fails to renew them.

How Did Marriage Get Penalized in the First Place? Prior to 1968, single filers paid more in taxes than married filers with the same combined income. For example, a single earner with an income of $15,000 a year in 1968 paid 32 percent of his income in taxes, while a married couple paid 25 percent. In essence, because of this “marriage bonus,” a single person could pay up to 40 percent more in taxes than a married couple with the same income.

Because it penalized singles, the tax code was changed in 1969 to eliminate the marriage bonus for couples who filed jointly. Income brackets for married couples were reduced to less than twice the amount for single filers. But, as a result, married couples with rising incomes reached the higher tax-rate thresholds sooner than single people with similar incomes. For example, in 2000:

- Before the Bush tax cuts, a single filer with a taxable income of $25,000 paid taxes at the 15 percent rate.

- But if that person married someone who also earned a taxable income of $25,000, both parties were pushed into a higher tax bracket, with a marginal rate of 28 percent.

That is the same marginal rate at which a married couple with one earner making $100,000 would be taxed!

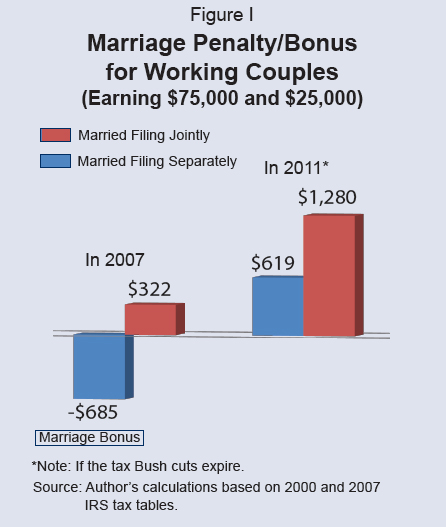

The Present-Day Marriage Penalty. Prior to the Bush tax cuts, an estimated 25 million couples paid a penalty for being married in 1999, amounting to about $1,141 per couple. However, the Bush tax cuts of 2001 made the income bracket for married couples twice that of single filers for incomes up to the 25 percent tax bracket. That virtually eliminated the marriage penalty for low- to moderate- income workers, and mitigated it for higher-income earners. (There is still a small penalty for high-income couples filing separately.) However, the marriage penalty will return if the Bush tax cuts are allowed to expire [see Figure I]:

- In 2007, a married couple filing jointly with taxable income of $25,000 and $75,000 actually paid about $685 less than if they were single.

- If the couple filed separate returns, they paid about $322 more in taxes than if they were single.

- If the Bush tax cuts expire, a married couple filing jointly in 2011 will pay about $619 more than the two singles; if the couple files separately, the penalty will be $1,280!

The Cost of the Marriage Penalty. Due to the dramatic shift of women into the labor force over the past 50 years, these penalties affect many more families. In 1970, only 40.5 percent of married women worked, while today 68.8 percent do. Two-earner families now comprise more than half of all families.

Spouses who enter the labor force as a second-earner (usually the woman) are at a particular disadvantage. They are taxed at their spouse's rate even if they only earn the minimum wage. This aspect of the tax system particularly burdens women — who are more likely to take time out from work to raise the family, either by taking lower-paying jobs with flexible schedules or by staying at home.

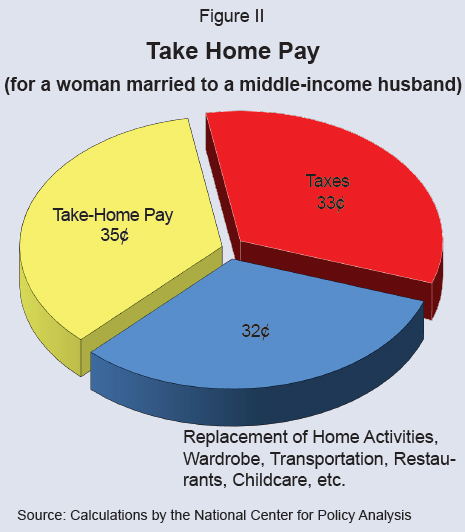

Adding to the high marginal tax rate on labor are other costs associated with working, such as child care:

- Child care costs range from $3,803 to $13,480 a year, according to the National Association of Child Care Resource and Referral Agencies.

- A two-parent family can expect to spend up to 10 percent of their income on these services.

- Adding taxes and child care costs to the cost of other services provided by a homemaker, a working mother can expect to keep about 35 cents of every dollar earned! [See Figure II.]

In this sense, the marriage penalty is more of a penalty on working than on marriage itself. If the marriage penalty returns and couples face higher tax rates, second-earner spouses will have less incentive to work.

Other Penalties on Working Couples. Despite the improvements in the tax code over the past seven years, the second-earner spouse is still taxed at the higher-earner's rate. Married couples are allowed to file separately, although they very rarely do so because they lose many other tax advantages, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit, Child and Dependent Care credits, education credits, and adoption exemptions and credits.

Other Penalties on Working Couples. Despite the improvements in the tax code over the past seven years, the second-earner spouse is still taxed at the higher-earner's rate. Married couples are allowed to file separately, although they very rarely do so because they lose many other tax advantages, such as the Earned Income Tax Credit, Child and Dependent Care credits, education credits, and adoption exemptions and credits.

Many of these credits and exemptions are granted mainly to low-income households. Even with two modest incomes, a couple can face high effective marginal rates because these tax credits are rapidly withdrawn as incomes rise. Thus, in order to make the tax system fairer to two-earner couples, the income qualification for some of these tax benefits was doubled over the past few years. If these higher income ranges are allowed to expire, married couples will face additional penalties. For example:

- The standard deduction of $10,700 for joint filers will revert to less than twice the deduction for single filers (currently $5,350).

- The tax credit for taxpayers with children will fall 50 percent, from $1,000 to $500.

Low- and middle-income families will be struck the hardest by these changes in 2011.

Conclusion. With nearly 70 percent of women providing a second income for their family today, they face the decision to either bear a greater share of the tax burden for their choice to pursue a career or stay at home as a homemaker. The current tax laws need to be renewed before 2011 and updated to allow married couples to file individually without losing the tax benefits associated with marriage.

Daniel Wityk is a research assistant with the National Center for Policy Analysis.