Since its inception in 1970, the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has been criticized for imposing large costs on businesses while producing only minimal improvements in workplace safety. OSHA is now required to show that the benefits of a proposed regulation outweigh the costs of complying with it. However, OSHA's cost-benefit analysis is often flawed.

For example, OSHA recently proposed legislation to regulate construction work in confined spaces, such as sewer and ventilation systems, underground vaults and silos. The rule would apply to construction firms, electrical and other utility contractors and water supply/irrigation companies. It requires contractors to classify and document all confined spaces on a construction site, distribute and collect entry permits, provide safety evaluations to employees entering confined spaces and maintain air quality data from the site for 30 years. Further, general contractors would be required to coordinate the activities of multiple sub-contractors with respect to their work in confined spaces.

OSHA estimates the annual cost of complying with the rule will be $77 million in 2002 dollars, and the benefits from improved safety will be $85 million, for a net benefit of $8 million per year. However, an examination of the data and assumptions underlying these estimates show they are deeply flawed. Estimates based on data updated to 2008 dollars indicate that the compliance costs will be much greater and the benefits much smaller than OSHA claims.

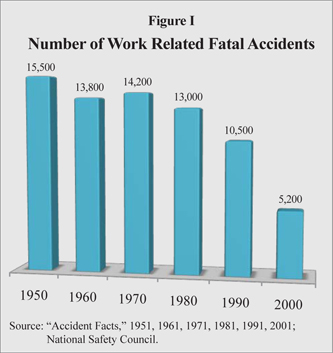

Workplace Safety Has Improved. Workplace injuries and fatalities fell steadily over the past half-century as employers improved safety practices and training [see Figure I]. OSHA's estimates of the reductions in nonfatal injuries and fatalities due to the proposed regulation are based on assumptions, not actual data. If OSHA had considered the downward trend in construction injury rates, the estimated regulatory benefits would have been less:

- From 1997 to 2006, the overall rate of construction injuries declined from 4.4 percent to 3.2 percent for every 100 full-time employees, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

- Injuries in confined spaces occur infrequently. In a survey of 2005 to 2007 construction industry accidents, the Associated General Contractors of America (AGC) reported no fatalities in confined spaces.

Because the industry has already achieved low rates of confined space injuries, it is highly unlikely that the new OSHA regulation will be able to lower the incidence further. Thus, the improvement in workplace safety will likely be less than OSHA claims.

Injury Costs Are Low. OSHA overstates the monetary value of the benefits of improved safety. It relied on decade-old data on construction industry characteristics; data from 2000 on entries into confined spaces, employee wages and benefits; and equipment prices from 2002. As a result, it overstates the monetary benefits of accident prevention.

Workers' compensation insurance funded by employer premiums pays for medical costs and wage replacement for individuals injured or killed in workplace accidents. But OSHA assumes the monetary cost of a fatality or serious injury is far higher than the actual costs of workers' compensation claims. The monetary value of increasing workplace safety would be considerably lower had OSHA used actual costs. Based on payouts from workers' compensation policies in 2000 and 2001, updated to 2008 prices to account for medical prices and general wage inflation:

- The average actual costs for a fatality were $262,580, not the $6.8 million OSHA estimates.

- The average cost in lost wages from a workplace injury was $35,578, in contrast to OSHA's $50,000 per case.

Regulatory Costs Outweigh Benefits. A study sponsored by the Associated General Contractors of America (AGC) shows that OSHA understates the cost of complying with the proposed rule, including the recordkeeping requirements, and the numbers of establishments, employees and industries affected. A survey of AGC members conducted for the study indicated that:

- For a typical employer, paperwork will consume 420 hours of employee time and safety training will require 62 hours, for a total cost of 482 hours annually.

- The time cost includes 240 additional hours per year from safety professionals and 104 hours from management employees.

- Given that safety professionals and management employees earn the highest wages in the industry (averaging $42.6/hour and $57.9/hour, respectively), the 482 hours of additional work represents about one fourth of a high-wage employee's annual hours and salary.

Additionally, in the first year, businesses would incur labor costs to modify existing training materials and to develop new procedures.

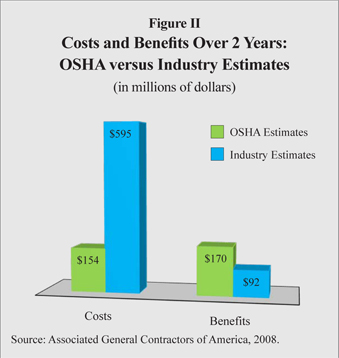

With updated information, the compliance costs are much larger and economic benefits much smaller than OSHA's estimates:

- The compliance costs would be $364 million in the first year of the rule's implementation and $231 million per year thereafter compared to OSHA's estimate of $77 million.

- The monetary value of the benefits would be $46 million per year in comparison to OSHA's estimated $85 million [see Figure II].

Furthermore, in the future, the monetary benefits of the rule will likely increase at a slower rate than the compliance costs because the projected injury rate reductions will not materialize.

Conclusion. Since the early 20th century, employers have had incentives to increase workplace safety. In fact, the financial liability of employers for workplace accidents – as reflected in their worker's compensation premiums – is the greatest incentive for employers to improve safety. Furthermore, increased workplace safety reduces employers' costs due to injuries and lost productivity. OSHA regulations, on the other hand, increase regulatory compliance costs, but don't necessarily improve safety. OSHA is supposed to justify proposed regulations with estimates of the expected costs and benefits, but using flawed analyses subverts the purpose of the requirement.

N. Mike Helvacian, Ph.D., is a senior fellow with the National Center for Policy Analysis.