Recent health care reform proposals have largely focused on achieving universal coverage through a combination of private-sector mandates, regulation of insurance premiums and expansion of government insurance. Proponents argue that adding more regulations and spreading costs across a wider insurance pool will make coverage more affordable. Reality belies these myths.

Myth No. 1: Employer Mandates Would Make Coverage Affordable. Requiring employers to either offer employees health insurance or pay a percentage of wages in fines would encourage more coverage, and thus reduce the number of uninsured.

Reality: Workers bear the full cost of their health coverage, either directly through contributions or indirectly through lower wages. Thus, an employer mandate really means that workers must receive a portion of wages in health benefits. Furthermore, if employers are forced to provide coverage that workers do not value as much as wages, the mandate has the effect of a tax on labor, discouraging employment and raising production costs.

Myth No. 2: Insurance Costs Can Be Limited to 10 Percent of Income. Families should not be required to contribute more than 10 percent of their income toward their health coverage or out-of-pocket medical costs (5 percent for low-income families).

Reality: What individuals do not pay in the marketplace must be covered by government. In other words, taxes would substitute for out-of-pocket premiums. Americans currently spend about 17 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), or nearly 20 percent of personal income, on medical care. Limiting out-of-pocket health care spending to 10 percent of income would not reduce costs. Instead it would disguise the true cost of medical care to consumers. Since a lavish policy would cost no more than a frugal one, families would have an incentive to over-insure and over-spend at taxpayers' expense. Moreover, even if subsidies reduced the cost of coverage for a year or two, premiums would soon begin to grow again. Currently, health spending is rising at twice the rate of workers' income, and would continue to do so. Subsidies would increase and, eventually, health care would be rationed to control costs.

Myth No. 3: Guaranteed Issue and Community Rating of Premiums Protect Consumers. Insurers should not be allowed to base premiums for individual health insurance policies on expected health care costs. All sectors of the community should share costs through even premiums (community-rating), whether young, old, sick or healthy. Insurers should not be allowed to refuse coverage to people who have serious medical conditions (guaranteed issue).

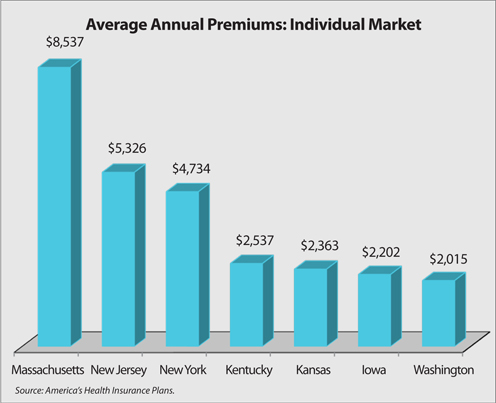

Reality: Regulations like guaranteed issue and community rating penalize the vast majority of consumers for the benefit of a small number of people. Although everyone pays a similar premium, healthy people pay more than they would otherwise so that sick people can be charged less. Thus, premiums rise for the majority of people. In every state with guaranteed issue and community rating, the cost of coverage is far higher than in states that do not have these regulations. New Jersey, New York and Massachusetts are good examples; a 2007 survey by America's Health Insurance Plans found that [see the figure]:

- An individual could purchase a policy for $2,537 a year in Kentucky but would pay about $5,326 in New Jersey.

- A similar policy, available for about $2,363 in Kansas, costs $4,734 in New York.

- A policy priced at $2,202 in Iowa costs $2,015 in Washington and $8,537 in Massachusetts.

Costly mandates make insurance a poor value for everyone except those with serious health conditions, and many people will wait until they become sick to buy coverage – just the opposite of the effect universal coverage advocates want!

Myth No. 4: Expanding Government Insurance Improves Access to Care. Expanding eligibility for Medicaid or the State Children's Health Insurance Program (S-CHIP) would improve access to care for lower-middle income families.

Reality: In practice, things are different. On paper, Medicaid coverage appears more generous than the benefits the vast majority of Americans receive through private health insurance. Potentially, Medicaid enrollees can see any doctor or enter any facility and pay nothing. In fact, the uninsured and Medicaid patients do tend to get their care at the same hospitals, clinics and emergency rooms. But the availability of other providers is limited: Nationally, one-third of doctors do not accept any Medicaid patients and, among those who do, many limit the number they will treat. Studies have shown that access to care at ambulatory (outpatient) clinics is also limited for Medicaid patients, as is access to specialist care.

Another problem is that expanding public coverage encourages people to drop their private health plan to take advantage of the free program – leading to a phenomenon known as "crowd-out." For instance:

- For every new dollar of spending on Medicaid expansions in the 1990s, between 49 and 74 cents went to people who had dropped private coverage.

- The crowd-out rate for S-CHIP averages is about 60 percent.

- Hawaii recently abandoned its universal child health care program after state officials discovered 85 percent of newly enrolled kids had dropped private coverage.

As income rises, so does the likelihood that families will be covered by private insurance. Thus, increasing eligibility for public coverage also increases the likelihood that a family will drop better quality private coverage.

Conclusion. Most health reform proposals designed to achieve universal coverage by making health insurance more affordable are based on myths about how health insurance should work. They would impose regulations that would increase the cost of coverage for most people and boost expenditures. As a result, consumers would have fewer choices and less control over their health care.

Devon Herrick, Ph.D., is a senior fellow with the National Center for Policy Analysis.