Socially responsible investing (SRI) is the practice of choosing stocks, bonds or mutual funds based on political, religious or social values. This investment strategy can be hazardous to an individual's portfolio, and if followed by state and local employee pension funds can adversely affect thousands of people's retirement incomes.

Investment Strategies. According to Kelly Ford of the Motley Fool, there are three basic SRI strategies.

Avoidance investing is the most prevalent SRI strategy. It involves avoiding purchasing stock in corporations with certain products – typically tobacco, alcohol or gambling, but also nuclear power, fossil fuels and other products considered environmentally unfriendly. While excluding certain companies from a fund's portfolio does not have a major impact on the practices of the avoided industries, a screen that is too broad can leave little in which to invest.

Activist investing involves acquiring shares in companies whose policies one wishes to influence. This may require buying stock in companies that would not pass a social screen in order to influence corporate decisions – for instance, by voicing concerns at annual shareholder meetings. An advantage is that a shareholder reaps any gains and dividends from the company's success while working to change its policies. The main disadvantages are that it requires a large time commitment and significant stock holdings in order to have any affect.

Socially focused investing involves depositing funds or buying stock in community banks and credit unions that serve local minority communities or environmental causes. Investors tend to focus on positive community screens such as happy workforces, quality products, healthy community relations, sustainability practices and good balance sheets.

Size and Scope of Social Investing. SRI funds account for a relatively small portion of total investment. However, they have grown rapidly in recent years due to shifting public perceptions of corporate social responsibility. According to the trade association Social Investment Forum:

Size and Scope of Social Investing. SRI funds account for a relatively small portion of total investment. However, they have grown rapidly in recent years due to shifting public perceptions of corporate social responsibility. According to the trade association Social Investment Forum:

- Of $25.1 trillion in U.S. equities, an estimated $2.71 trillion is invested by individuals or mutual funds using one or more of the three core socially responsible investing strategies.

- The number of socially-screened mutual funds has grown from 55 in 1995 to 260 in 2007.

- Socially-screened mutual funds have $208.1 billion in assets.

Rate of Return on SRI Funds. The screens used by SRI mutual funds and individual investors are largely ideological. They can also be illogical. For example, a socially responsible mutual fund may have holdings in a company that would normally be eliminated on a negative social screen, but that still has positive business practices. Conversely, it can mean an investor might eliminate renewable energy companies because of inadequate employee benefits, or invest in airlines that have progressive hiring practices but also have huge carbon footprints.

SRIs also generally have lower rates of return due to their investment makeup. According to Consumer Reports, from 2003 to 2008:

- SRI funds returned 11.1 percent annually while all domestic equity funds (stocks) returned an average of 14.5 percent.

- Only 15 percent of SRI funds with five-year track records returned over 11.1 percent.

- Moreover, SRI funds usually have higher fees and expenses than typical mutual funds.

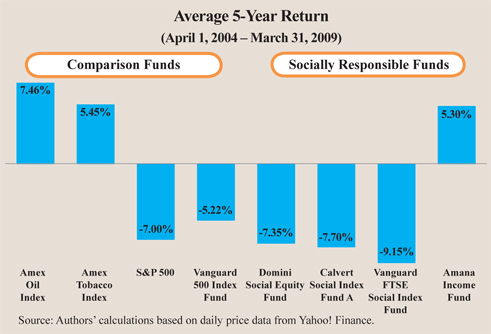

Take the five-year average return of four typical investments that are usually screened out by SRI funds, compared to four of the largest socially responsible mutual funds [see the figure]:

- Over a five-year period, the four regular funds outperformed the four SRI funds.

- The Amex Oil index topped the charts with a five-year return of 7.46 percent, and the worst performing fund was the Vanguard FTSE Social Index Fund at -9.15 percent.

- Amana, with a return of 5.30 percent, was the only SRI fund whose performance approached those of the regular funds.

- Even the worst performing regular fund, the S&P 500 Index, did better than three of the SRI funds.

SRI Funds and State Pensions. In the United States, state and local governments control more than one-third of the $6.7 trillion in aggregate pension fund assets. The investment of these assets can be driven by social and political motivations that reduce returns.

State Pension Funds and Tobacco Companies. Some state pension funds have completely divested their portfolios of tobacco company stocks. In 2000, the California Public Employees Retirement System and the California State Teachers Retirement System sold all $800 million of their tobacco shares. As a result, they lost an estimated $1 billion over eight years.

State Pension Funds and Labor Practices. In 2005, a group of Massachusetts shareholders and activists pressured the state's education pension system to divest from Wal-Mart and Coca-Cola, citing alleged mistreatment of workers, particularly in other countries. The Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association – College Retirement Equities Fund (TIAA-CREF) has not yet divested, but activists are pressuring it to engage in dialogue with the CEOs of Wal-Mart, Coca-Cola and Nike to change their policies.

State Pension Funds and Developing Countries. Since the days of divestment from South Africa over apartheid, socially conscious investors have targeted firms that invest in countries where human rights are abused. For example:

- Currently, 22 states have enacted laws that divest pension funds from Sudan.

- Eleven cities and 54 colleges have also divested funds from Sudan.

- California has gone a step further by divesting funds from emerging market countries for limiting worker freedoms, including Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand.

However, with so many firms operating internationally, it can be difficult to screen out those that operate in countries engaging in questionable human rights practices. Moreover, emerging market countries tend to offer higher investment returns.

Conclusion. The fiduciary responsibility of state pension funds requires that they base their decisions on maximizing the value of employees' investments, rather than making moral or political judgments. Conflicts between this responsibility and individual scruples could be avoided by allowing individuals to choose their own investment vehicles, as in 401(k)s or Individual Retirement Accounts.

Allison Hughey is a research assistant and Pamela Villarreal is a senior policy analyst with the National Center for Policy Analysis.