Many people assume Medicare will cover most of their health care costs when they retire, and that Medicaid, the health care program for the poor, will cover them if they need nursing home care. However, neither program guarantees a low-cost ride through retirement.

Research has shown that seniors can expect Medicare to cover only about half of their medical expenses, on average. According to Fidelity Investments, the average senior retiring at age 65 this year will need $240,000 to pay the out-of-pocket costs of health care for the rest of his or her life.

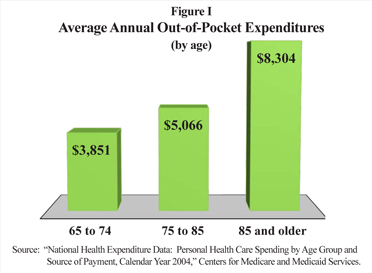

Seniors and Out-of-Pocket Expenses. Seniors spend more per capita on out-of-pocket health care expenses than any other age group. The 2004 National Health Expenditure Survey found that:

- Seniors age 65 and over spent an average of $4,888 per capita annually out of pocket for deductibles, copayments, premiums and other health care expenses not covered by insurance.

- Their spending is more than twice as high as the average nonelderly adult.

- The largest expenditures occurred among those 85 and older, who spent an average of $8,304, compared to $5,066 for seniors ages 75 to 84, and $3,851 for those 65 to 74. [See Figure I.]

Seniors and Medicare. There are three potential cost components to the Medicare program for seniors. Part A, which covers inpatient hospital stays and rehabilitation, is paid for through all employees' payroll taxes, but seniors still face copays and deductibles. Part B mainly covers physician services and is partially paid for through premiums deducted from seniors' Social Security benefits checks.

Seniors and Medicare. There are three potential cost components to the Medicare program for seniors. Part A, which covers inpatient hospital stays and rehabilitation, is paid for through all employees' payroll taxes, but seniors still face copays and deductibles. Part B mainly covers physician services and is partially paid for through premiums deducted from seniors' Social Security benefits checks.

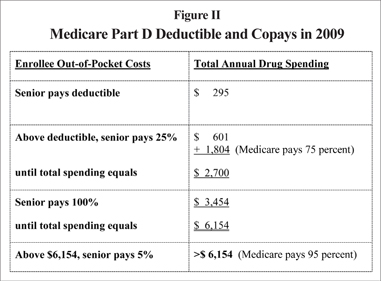

Part D, the prescription drug benefit enacted in 2006, is provided by private insurance plans approved by Medicare. Premiums vary by plan and geographic area, but the monthly average is about $24 and the average out-of-pocket deductible for 2009 is $295. However, there is a so-called "donut hole" in Part D plan benefits. Once seniors have used $2,700 in drug benefits, they pay the full cost of drugs until they spend a total of $4,350 out of pocket. [See Figure II.]

In addition, there are potentially expensive "Medigap" plans available to fill the coverage gaps in Parts A and B. Many lower-income seniors turn to Medicare Advantage plans offered by private insurers. The coverage is more comprehensive than traditional Medicare, but enrollees pay only a single, government-subsidized premium.

Seniors and Medicaid. Since Medicare does not cover long-term nursing home care, many seniors depend on Medicaid. In fact, Medicaid picks up the tab for about 42 percent of aggregate nursing home costs. However, seniors must meet income and asset requirements, which vary by state. Many seniors deplete their assets to qualify. For instance:

- Seniors eligible for Medicaid long-term care benefits can keep a house and a car – but their home equity cannot exceed $500,000.

- Their financial assets cannot exceed $2,000 for singles and $3,000 for couples.

- They cannot have transferred assets to other family members within five years of applying for Medicaid.

To discourage beneficiaries from hiding assets, new federal laws have expanded the assets counted in determining eligibility. However, at-home spouses are allowed a monthly income of 200 percent to 300 percent of the poverty level.

To discourage beneficiaries from hiding assets, new federal laws have expanded the assets counted in determining eligibility. However, at-home spouses are allowed a monthly income of 200 percent to 300 percent of the poverty level.

Some states have implemented private-public long-term care partnership programs. Seniors purchase a minimum level of private long-term care insurance. If their private coverage runs out, Medicaid will cover their long-term care costs without requiring them to spend down all of their assets.

Private Long-Term Care Insurance. Medicaid nursing home care is not for those who want to maintain a higher standard of living or leave some assets to their heirs. However, there is little incentive for individuals to purchase private long-term care insurance, and few benefit from the current tax deduction:

- At the federal level, private long-term insurance premiums are only partially tax deductible, and only if out-of-pocket health expenses exceed 7.5 percent of the filer's adjusted gross income.

- IRS rules allow a larger portion of the premium to be deducted as the age of the senior increases, limited to $3,980 annually after age 70.

Meeting Retirement Health Care Costs. In general, retirees are not eligible for Medicare until they reach age 65, even if they apply to receive Social Security benefits earlier. Older, laid-off workers might consider COBRA [Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act] coverage. COBRA allows involuntarily terminated workers to stay in their employer's health plan for up to 18 months, provided they pay the premiums. Although COBRA is usually cheaper for this age group than individual health insurance, it still averages over $4,500 a year.

Seniors should look for ways to reduce their health care expenses. Many seniors can avoid the Part D coverage gap. Medicare.gov is a Web site seniors can use to estimate their monthly costs for drugs and premiums under different Part D plans. It also offers suggestions for therapeutic substitutes that may cost less than prescription drugs.

Public policy changes should be made. These include using health insurance retirement accounts to provide current workers with incentives to partially prepay future Medicare costs through savings. Seniors could also save for post-retirement medical expenses if they were allowed to continue funding a Health Savings Account after they reach age 65. Finally, premiums for private long-term care insurance should be tax-deductible, regardless of the purchaser's age, or how much of a household's adjusted gross income goes toward health care costs.

Pamela Villarreal is a senior policy analyst and Devon Herrick is a senior fellow with the National Center for Policy Analysis.