Some members of Congress want to raise excise taxes to pay for health care reform and energy technology development. Federal excises on tobacco and alcohol are often called sin taxes; others designed to pay for specific government services, such as gas taxes that fund road building and maintenance, are often called user fees.

Proponents claim excise taxes are more efficient than other taxes. They are easier to collect, they are paid by those who benefit from a service, or they offset the costs individuals impose on society due to their bad habits. However, the evidence shows that these taxes are often inefficient, ineffective and unfair.

New Excise Taxes. In February 2009, President Obama signed legislation increasing the federal cigarette tax from 39 cents to $1.01 a pack to fund expansion of the State Children's Health Insurance Program (S-CHIP). The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates this and other tobacco tax increases will raise $72.1 billion over the 2009 to 2018 period.

Additionally, the Obama administration has considered imposing a soda tax on all sugary beverages to fund health care reform. A 2009 New England Journal of Medicine article claims that high-sugar drinks are one of the leading causes of obesity. Health care for the obese and overweight costs an estimated $79 billion annually, with taxpayers picking up about half the tab through Medicare and Medicaid. Supporters argue that a soda tax would discourage people from drinking soft drinks and would raise revenue to pay for the cost of treating obesity-related illnesses. The CBO estimates a soda tax of 3 cents per 12 ounces of beverage would raise $50 billion over 10 years.

The Senate Finance Committee has also proposed increasing alcohol taxes. Taxes would rise from $2.14 to $2.54 on a 0.75 liter bottle of distilled spirits, from 33 cents to 81 cents on a six pack of beer, and from 21 cents to 70 cents on a 0.75 liter bottle of wine. In total, this would raise $60 billion from 2009 to 2018, according to the CBO.

The National Surface Transportation Infrastructure Financing Commission (NSTIFC) projects a $78 billion average annual deficit in federal highway funding between 2008 and 2035. It has proposed a 10 cent federal gas tax and 15 cent diesel tax increase – generating nearly $20 billion a year – to partially meet this shortfall.

Inefficient at Raising Revenue. If the price of a product rises high enough to discourage consumption, an excise tax hike will not produce the expected revenue increase. For example, gas tax revenues have grown more slowly than anticipated as people switch to more fuel efficient vehicles and buy less gasoline. An NSTIFC report acknowledges that the gas tax is inadequate "as the primary source of federal surface transportation funding beyond the next 10-15 years."

Ineffective at Changing Behavior. In theory, excise taxes should discourage the consumption of the items or services taxed. In practice, they fail to produce the full extent of desired behavioral changes. This is because the demand for many of the products typically taxed is inelastic, which means that people's consumption is somewhat insensitive to price changes. If the demand for gas, tobacco and junk food were elastic, consumption would decrease rapidly as the higher tax rate increased prices. As consumption of the product fell, the higher tax rate would produce little or no additional revenue. But people are generally reluctant to give up gas, cigarettes – or soft drinks.

Also, higher excise taxes may encourage substitution. Cigarette smokers may substitute cheaper cigarettes for more expensive ones, or soda drinkers may turn to other sugary drinks. Additionally, excise taxes may encourage grey and black markets, where buyers import cigarettes or alcohol from foreign countries that don't tax these products or obtain untaxed goods in other illegal ways.

These may be some of the reasons why economists Jason M. Fletcher, David Frisvold and Nathan Tefft found that:

- Increasing the soft drink tax by 55 percentage points would decrease the obese and overweight population by only 0.7 percentage points.

- That means a 27.5 cent tax on a 50 cent can of soda would only lower the number of the obese and overweight from 66 percent to 65.3 percent of the population.

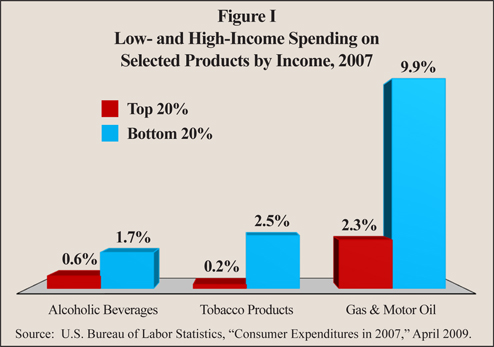

Burden on the Poor. Furthermore, low-income families spend more of their incomes on products subject to excise taxes than higher income families, making excise taxes very regressive. A Bureau of Labor Statistics report, "Consumer Expenditures in 2007," shows that [See Figure I]:

- On average, the bottom fifth of income earners spend 1.7 percent of their gross income on alcoholic beverages compared to 0.6 percent for the top 20 percent.

- They spend 2.5 percent of income on tobacco products versus 0.2 percent for the top 20 percent.

- They spend 9.9 percent on gasoline and motor oil compared to 2.3 percent for the top 20 percent.

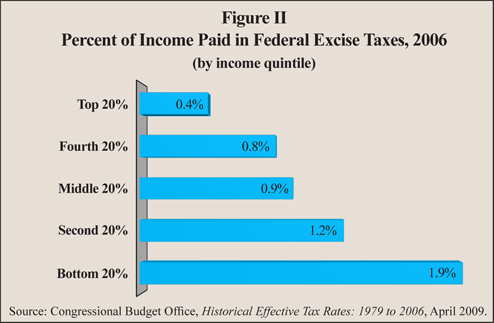

Looking at all federal excise taxes combined, the CBO estimates that the bottom fifth of income earners pay 1.9 percent of their income in excises versus 0.4 percent for the top fifth [See Figure II].

Conclusion. Any benefit from excise taxes offsetting the cost of harmful behaviors is overshadowed by their inefficiency, ineffectiveness and regressivity. A better approach is to balance the budget and reallocate resources from other programs toward priorities like health care and energy development.

D. Sean Shurtleff is a policy analyst with the National Center for Policy Analysis.