Americans have been saving less and less of their after-tax income for the past 15 years. The annual personal savings rate averaged 8 percent from 1929 to 2000, but reached a historical low of 0.4 percent in 2005. With the onset of the 2008-2009 recession, however, the savings rate rose again to more than 6 percent.

Over the past three decades, savings in tax-advantaged accounts, such as 401(k)s and Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs), have increased dramatically. These accounts are specifically designed to meet retirement expenses. For other purposes, individuals must save after-tax money from their take home pay.

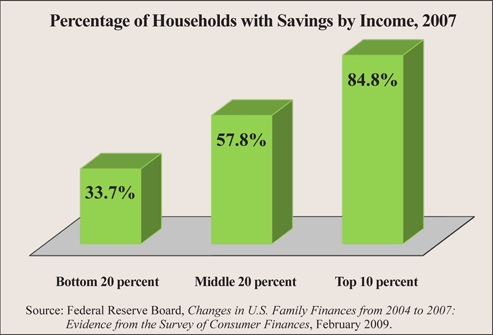

Low-income workers, however, have a low rate of saving of any kind. The Federal Reserve reports that only one-third of families in the bottom fifth (incomes of less than $20,291) saved any of their income in 2007, compared to almost three-fifths of households in the middle fifth (incomes between $39,000 and $62,000). [See the figure.] Without savings, low-income families have no resources to invest in efforts to increase their human capital, such as education and job training to improve their skills, or in physical assets such as housing and transportation to help them move out of poverty. They also lack emergency funds to draw on during recessions.

There are programs to encourage savings by low-income workers. They generally depend on providing additional funds (a match) for each dollar saved. However, there is evidence that a more effective approach would be a program designed to make the savings option as easy as possible, supplemented by a savings match.

Matching Funds for Retirement Savings. To encourage retirement savings by low-income workers, the federal government has the Saver's Credit, a tax credit of up to $1,000 ($2,000 for joint filers). Depending on income, the taxpayer receives what is, in effect, a match of up to $1 for each dollar they save in a retirement account. A 2006 National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) study found that receiving a higher credit – in effect moving from a 25 percent to 100 percent match – increases participation by only 1.3 percentage points. The Saver's Credit is not refundable, however, which means that low-income tax filers with no tax liability against which to apply the credit do not benefit. In fact, few eligible taxpayers use the credit.

Matching Funds for Individual Development Accounts. Individual Development Accounts (IDA) provide matching funds for each dollar saved by participating low-income households. Match rates vary from $1 to $8 for every $1 contributed by the individual. The accounts are managed and funded by nonprofit organizations with subsidies from the federal government. The savings can be used only for postsecondary education, or to purchase a home or a business.

A 2008 study by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services found that IDAs encourage medium-term saving and help build assets among participants:

- After 3 years in the program, 42 percent of IDA participants were homeowners, compared to 31.1 percent of comparable low-income workers not in the program.

- More than a fifth (21.9 percent) owned a small business, nearly twice the proportion of comparable workers (11.9 percent).

- Some 43.5 percent were pursuing postsecondary education versus 22.3 percent of other workers.

Matching Funds for Saving Tax Refunds. The same NBER study found that low-income tax filers will save part of their tax refund in an IRA if given matching funds. Low-income households filing tax returns at H&R Block locations in St. Louis were either offered no match, or a match of 20 percent or 50 percent. The results:

- Three percent of households in the no-match group saved part of their refund in an IRA.

- Eight percent of the 20 percent match group saved part of their refund.

- Fourteen percent in the 50 percent match group saved part of their refund.

Thus, the match raised the participation by up to 11 percentage points.

Automatic Enrollment in EITC-Funded Savings Accounts. The preceding examples show that a match can have a small but significant effect on the savings rate of low-income workers. However, more dramatic increases in the rate of savings have come from changing the design of savings programs. For example, a 2001 NBER study found that automatically enrolling employees in a 401(k) retirement plan – requiring them to opt out of participation instead of opt into the plan – increases employee participation from an average of 35 percent to 92 percent. Automatic enrollment could also be applied to current benefit programs that give cash to low-income families with no conditions on the use of these taxpayer funds.

Take the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), a refundable tax credit that millions of employed low-income households receive even if they don't owe income taxes. On average, recipients get almost $1,700 a year in EITC refunds, according to the Tax Policy Center. Rather than send low-income workers a check when they file their tax returns, the federal government could deposit half of each EITC refund (an average of $850) into an IDA-like account. Tax filers would still receive half of the credit (an average of $850) in cash. As an incentive for additional savings, the government could also offer to match an additional fourth of the EITC refund (an average of $225) the tax filer chose to have deposited into the account. By contrast, tax filers who chose to opt out might only get three-quarters ($1,275) of their usual EITC check. Thus, the portion of the EITC benefit surrendered by those opting out would help pay for the EITC savings match.

Think of this as an automatic enrollment plus (AE+) account: automatic enrollment first, and a savings match as backup.

EITC-funded accounts could be integrated with existing IDA programs. Participants could also be allowed to withdraw money if they became unemployed or for other emergencies. This would be especially helpful during a recession because unemployed workers can lose their EITC benefit. Also, as with current IDAs, additional deposits could be made from personal income, welfare benefits, disability payments, unemployment checks and Social Security income. Furthermore, Congress could require the automatic deposit of future increases in the EITC into these IDA-like accounts.

D. Sean Shurtleff is a policy analyst with the National Center for Policy Analysis.