Growing public school enrollment, an increase in the number of teachers retiring or leaving the profession and legislated limits on class size have made finding competent educators a growing challenge. In recent years, all 50 states and the District of Columbia have established alternative certification programs to help meet this challenge. But have these programs been successful?

Shortage of Teachers. School districts must constantly recruit new teachers due to turnover. New hires are the most difficult to retain and only a minority stay in teaching for more than a few years. According to a nationwide study by the Nebraska State Education Association:

- Six percent of teachers leave the profession each year.

- One-fifth of new hires quit teaching within three years.

- In urban areas, 50 percent of educators quit after five years.

- As a result, many schools face a teacher shortage. According to the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES):

- In 2008, public schools required an estimated 2.2 million additional teachers.

- High-poverty urban and rural districts required more than 700,000 new teachers.

- The greatest shortages were in areas needing teachers with particular skills or knowledge of specific subjects, such as bilingual and special education programs, and mathematics and science classes.

Teaching  Credentials. A traditional teaching certificate or license typically requires a bachelor's degree in education, with 30 credits in teaching methodology and psychology, as well as field work. Course work also normally includes extensive study of the subject matter the person wishes to teach.

Credentials. A traditional teaching certificate or license typically requires a bachelor's degree in education, with 30 credits in teaching methodology and psychology, as well as field work. Course work also normally includes extensive study of the subject matter the person wishes to teach.

Each state has its own requirements for alternative certification, usually at least a bachelor's degree and general knowledge of the subject the person wants to teach. States and school districts have become more open to alternative certification. However, some state programs are very restrictive, limiting its success.

For example, education researchers Paul E. Peterson and Daniel Nadler found that many states' alternative certification programs require just as many college-level education courses as regular certification. As a result, these programs produce few new teachers. By contrast, less restrictive programs require significantly fewer hours of instruction and produce more teachers.

According to the National Center for Alternative Education, the oldest and most established state programs – in California, New Jersey and Texas – produce the most new teachers. Texas and California report that about one-third of their new teachers come from alternative programs. In New Jersey, it is about 40 percent.

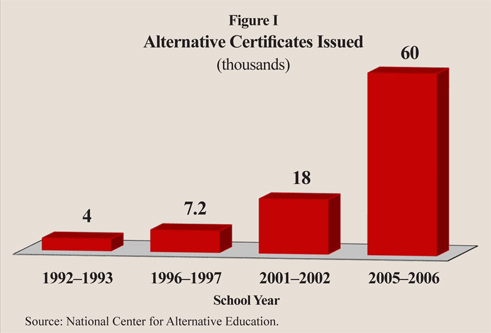

As Figure I shows, the number of alternative certifications issued each year has risen steadily since 1992, to nearly 60,000 for the 2005-2006 school year. These programs now play an important role in compensating for high turnover rates.

Experience and Teacher Effectiveness. NCES data suggest many teachers are inexperienced. About 30 percent of teachers have less than six years of experience, whereas only 7 percent have more than 30 years of experience. Teachers become more effective with time in the classroom, but does formal training make educators any better at teaching?

Measuring teacher effectiveness using student test score gains, a study of the New York City public school system by Thomas J. Kane, Jonah E. Rockoff and Douglas O. Staiger found alternatively certified teachers fared slightly worse initially than those formally trained, but quickly made up ground. In many instances, individuals alternatively certified surpassed traditional teachers.

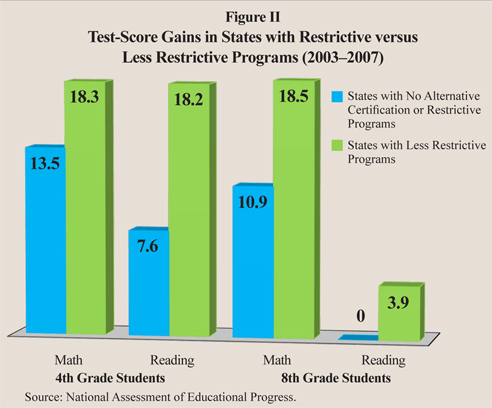

In a separate study, Peterson and Nadler compared state-level test results for 4th through 8th grade students on the National Assessment of Educational Progress. Among their findings [see Figure II]:

- From 2003 to 2007, in states with less restrictive alternative certification, 4th grade students gained 18.3 points in math, on average, while students in states that have no program, or restrictive programs, gained only 13.5 points.

- In reading, 4th graders in states with less restrictive alternative certification gained 18.5 points, compared to a 7.6 point average gain in states with restrictive programs.

- In the 8th grade, students in less restrictive states saw gains of 18.5 ponts in math and 3.6 points in reading, while students in restrictive states had gains of only 10.9 points in math and zero points in reading.

Furthermore, a 2001 study by the National Center for Education Evaluation found no statistical difference between the academic achievement of students taught by alternatively certified teachers and those taught by traditionally certified teachers.

Conclusion. Alternative certification programs attract individuals who are committed to teaching and whose non-teaching experiences are valuable in the classroom. Because alternatively certified teachers are just as effective as traditionally certified teachers and are necessary to compensate for the high turnover rate of teachers, alternative certification programs ought to be expanded and embraced by states and school districts.

Rebecca Garcia and Jessica Huseman are research assistants with the National Center for Policy Analysis.