In fall 2008, the stock market suffered a severe decline. Fear prompted a number of individuals to suspend contributions to their 401(k) retirement accounts. They reasoned that holding the money and having it retain its face value was preferable to putting it in a money-losing investment. Even employees who were invested in bonds, rather than equities, stopped contributing. Some companies temporarily suspended their matching contributions.

How Large Were the Losses? According to the Employee Benefit Research Institute (EBRI), 401(k) participants with the highest account balances experienced the greatest losses. From January 1, 2008, to January 1, 2009, including contributions:

- Accounts with balances greater than $200,000 lost about 25 percent.

- Accounts with $10,000 to $50,000 neither lost nor gained.

- Accounts of less than $10,000, by contrast, gained more than 40 percent.

Furthermore, long-term investors closer to retirement lost the most value. For instance:

- Workers aged 45 years and older who participated 20 to 30 years lost about 25 percent of their 401(k) balances, as did workers ages 55 to 64 who had invested 30 years or more.

- In contrast, younger workers ages 35 to 44 who had invested for 10 to 19 years lost about 20 percent.

- Finally, the youngest workers, who had invested five to nine years, gained nearly 5 percent.

Smaller accounts fared much better because monthly contributions more than made up for losses, while deposits to the larger accounts did not. Of course, these figures assume that an individual does not cash out his 401(k) account. Income taxes on 401(k) contributions and accumulated earnings are deferred until withdrawn at retirement, when an individual may be in a lower tax bracket. Withdrawing funds prior to retirement triggers taxes and penalties.

Why Stop Contributing? According to Hewitt Associates, an employee benefit consultancy, about 4 percent of 401(k) participants stopped contributing to their plans in 2008. Following are some common reasons for halting contributions – or worse, withdrawing funds – and why they don’t hold water.

“If the market dips further, I’ll lose money.” This is true, but it may not be as bad as it sounds. A $100 employee contribution purchases shares of a mutual fund the employee selects. If the fund costs $10 a share, he has purchased 10 shares. If the employer immediately matches the contribution one-to-one, $200 has been allocated to the purchase of 20 shares.

But if the fund drops 50 percent to $5 a share two weeks later, half of the $200 contribution is lost. However, because the employee contributed only $100, he is no worse off. Moreover, at $5 a share, the next $100 contributed will purchase twice as many mutual fund shares, and when the price-per-share rises with the market the employee will enjoy gains on a larger number of shares.

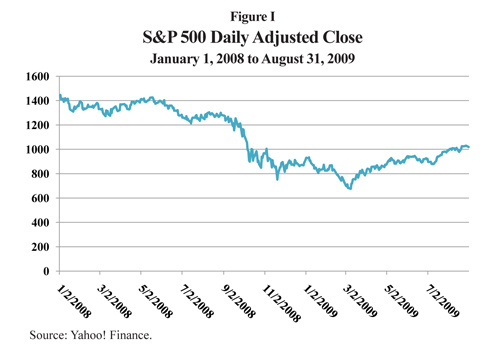

Bear in mind: Unless a worker cashes out his 401(k) account, there is usually plenty of time to recoup losses. In fact, Standard and Poor’s 500 – a composite of leading stocks whose performance many index mutual funds guarantee to match – has already returned to its early October 2008 level. [See Figure I.]

“My employer suspended the match.” Currently, less than 2 percent of employers have suspended their matching contributions. Meanwhile, taxes will eat away at the employee’s $100 if it is not invested (see the final claim below).

“I’m better off putting my money in the mattress until my 401(k) account improves.” Hiding money in a mattress was common following the 1929 stock market crash. In today’s world, a worker simply stops contributing to his 401(k).

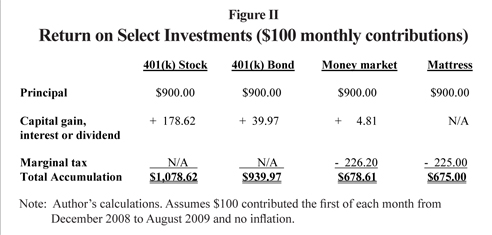

Figure II illustrates how much that worker could have earned on nine consecutive monthly contributions of $100 ($900 total):

- A $100 a month (tax-deferred) contribution to an S&P index fund (Fidelity) beginning December 1, 2008, would have yielded $1,078.62 by August 31, 2009.

- The same contribution to a bond index fund (Fidelity) would have yielded $939.97 by the end of the period.

- A $100 a month (taxable) contribution to a savings account invested in money market funds would have yielded $678.61 by August 31, including losses to the federal income tax, assuming a marginal income tax rate of 25 percent.

- Finally, hiding the money under the mattress would have yielded a 0 percent rate of return and it would have incurred federal income taxes, reducing the $900 to $675 by the end of the period, assuming a 25 percent marginal tax rate.

Roth Savings. It is also important to note that after-tax contributions to a Roth 401(k) retirement plan will earn more than money left at home. For instance:

- An after-tax contribution of $75 a month (total $675) to a Roth 401(k) in the Fidelity Spartan Stock Index fund would yield $891.29.

- Contributing $75 a month (total $675) to a Roth 401(k) in the Fidelity Bond Index fund would yield $704.98.

Conclusion. Despite the bad news, EBRI reports that the average balance in 401(k) accounts with the fewest years of contributions (6 to 10 years) more than tripled between January 1, 2000, and January 20, 2009. Long-established accounts (21 to 30 years) gained at least 29 percent during the period. These results demonstrate that the best strategy for any saver is to keep investing.

Pamela Villarreal is a senior policy analyst with the National Center for Policy Analysis.