The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) considers housing affordable if it costs less than 30 percent of a family's income. Yet, according to HUD, 12 million renters and homeowners spend more than 50 percent of their income on housing. Many of these are low-income individuals or families. But in some areas even middle-income families find the supply of affordable housing limited.

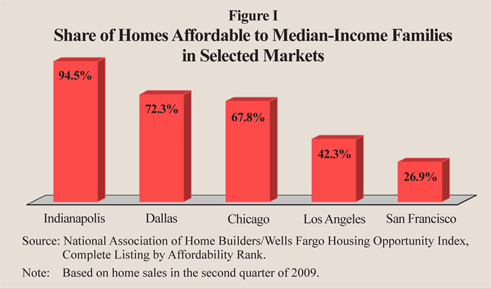

For instance, assuming a family spends no more than 28 percent of its gross income on housing [see Figure I]:

- In the San Francisco metropolitan area, only 26.9 percent of houses sold are affordable to a family with an annual median income of $96,800.

- In greater Chicago, more than two-thirds (67.8 percent) of houses are in the price range of a median income family ($74,600).

- In Indianapolis, almost all homes (94.5 percent) are affordable to the typical family ($68,100).

Since rental prices closely track home prices, these numbers also indicate the general availability of affordable housing.

Obstacles to Affordable Housing. According to a 1991 HUD report, local government policies that increase building costs and/or restrict the supply of housing are one of the primary reasons for the lack of affordable housing.

Obstacles to Affordable Housing. According to a 1991 HUD report, local government policies that increase building costs and/or restrict the supply of housing are one of the primary reasons for the lack of affordable housing.

Regulations. These range from minimum lot sizes that encourage larger and more expensive homes to the prohibition of multifamily dwellings. In some communities, regulations have raised the cost of new development and construction by 35 percent. A 2005 follow-up HUD report found that in more heavily regulated localities rents were 17 percent higher; home prices, 51 percent higher; and homeownership rates, 10 percent lower compared to less-regulated areas. Impact fees and inclusionary zoning are particularly costly. If these costs were reduced, more affordable housing would be available.

Impact Fees. Many communities impose fees on developers and homebuyers that must be paid in advance of new construction. The fees are supposed to recoup the cost of connecting roads and sewer lines. But the fees are often far higher than the new infrastructure costs. For example, in 2001, many households in Alachua County, Florida, paid fees more than $3,000 higher than their share of infrastructure costs, according to HUD.

Inclusionary Zoning. Many communities have tried to increase the supply of affordable housing through inclusionary zoning laws. These laws give builders incentives, or require them, to reserve a portion of new units for low and/or moderate-income households. Numerous California communities have adopted inclusionary zoning; but, in fact, the regulations have made housing less affordable than ever. According to a 2004 Reason Foundation study:

Inclusionary Zoning. Many communities have tried to increase the supply of affordable housing through inclusionary zoning laws. These laws give builders incentives, or require them, to reserve a portion of new units for low and/or moderate-income households. Numerous California communities have adopted inclusionary zoning; but, in fact, the regulations have made housing less affordable than ever. According to a 2004 Reason Foundation study:

- New home prices increased by up to $44,000 in 45 San Francisco Bay Area cities that enacted inclusionary zoning laws.

- Inclusionary zoning in Los Angeles and Orange Counties increased the price of new homes by up to $66,000.

Increasing the Availability of Affordable Housing. Innovative housing solutions, such as manufactured housing and single resident occupancy (SRO) dwellings, would help alleviate the shortage of affordable housing. These solutions would require local governments to remove regulatory barriers by adopting more flexible building standards and less restrictive zoning.

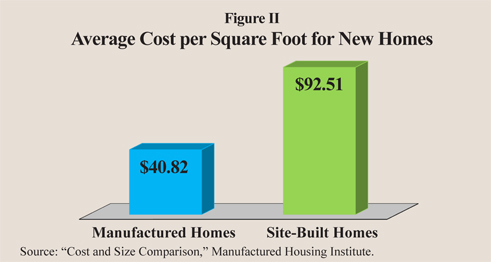

Manufactured Housing. In 2007, a manufactured home cost $40.82 per square foot, while a traditional site-built home cost more than twice as much – an average of $92.51 per square foot. [See Figure II.] However, municipal regulations often limit residential construction to traditional site-built homes, and prohibit manufactured housing altogether. It is often claimed that manufactured housing decreases adjacent property values; however, a joint study by Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology found that manufactured homes have no impact on the property values of adjacent site-built homes.

Single Resident Occupancy. Between 1974 and 1983, according to the Reason Foundation, 896,000 housing units renting for less than $200 per month were demolished – many of them were single resident occupancy (SRO) dwellings. A typical SRO consists of individual rooms with shared kitchen and bathroom facilities, although some have private kitchens and/or bathrooms.

SROs are illegal in many cities. However, they could significantly increase the supply of affordable housing for low-income single adults. For example, after the number of SRO units declined due to downtown redevelopment in the 1970s and 1980s, San Diego relaxed zoning and building regulations to encourage SROs. From 1986 to 1996, says the Reason Foundation, 2,400 new SRO units were built, adding to the 3,000 existing units.

Alternative Housing. Affordable housing might be built using alternative materials and construction techniques, such as strawbales and geodesic domes, but local ordinances often restrict the materials that can be used. In some cities, steel cargo containers that carry freight by truck, rail and ship are being converted into housing. A Fort Worth, Texas, nonprofit organization called A Place to Sleep recently proposed to construct an apartment-style community of affordable housing using 48-foot containers. According to the Star-Telegram, the organization estimates the cost per unit could be as low as $20,000 for a 408 square-foot home with a small kitchen and bathroom. Unfortunately, the plan was opposed by the local neighborhood, and prompted the Fort Worth City Council to inquire about changing zoning ordinances to discourage such construction.

Conclusion. Removing regulatory barriers to affordable housing solutions like manufactured housing and SROs would increase the supply of housing for individuals and families currently priced out of local markets.

James Franko is a legislative assistant with the National Center for Policy Analysis.