The estate tax is not yet dead, by a long shot. Federal taxes on estates fell as a result of the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 (EGTRRA). In fact, the estate tax will even disappear for one year (2010) due to EGTRRA. In 2011, it is scheduled to return with a higher tax rate and lower exemption than before. However, Congress is expected to pass legislation applying the tax retroactively to those who die in 2010.

There are a number of reasons to permanently repeal the estate tax, including the economic damage it does, the fact that it doesn't raise any net revenue and the confiscatory tax rate it can impose, at the margin – even on middle class taxpayers.

Higher Marginal Estate Tax Rates for 2011. The estate tax is progressive – that is, it rises with the size of the estate. EGTRRA gradually lowered the top tax rate from 55 percent to 45 percent for 2007 to 2009. The amount of estate exempted from the tax rose from $650,000 to $2 million in 2007 and 2008, and to $3.5 million in 2009.

EGTRRA is scheduled to sunset in 2011, when the estate tax will return and rates will revert to those in effect prior to 2001 – up to 55 percent. The first $1 million of an estate will be exempt.

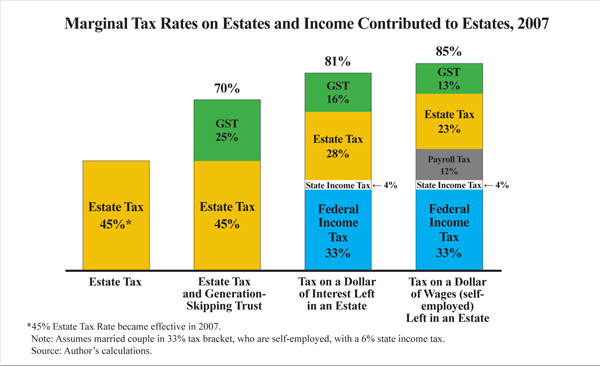

A Second Layer of Estate Taxation: The Generation-Skipping Tax. In addition to the estate tax, there is an added tax – called the generation-skipping tax (GST) – if a bequest goes to a grandchild or other relative more than one generation removed from the decedent. The GST rate is equivalent to imposing a 45 percent tax on the estate (as if it had gone to a child), and then imposing another 45 percent rate on the remaining 55 percent of the estate (as if it had gone from the child to the grandchild).

In 2007, the top rate for the combined GST/transfer tax reached nearly 70 percent. [See the figure.] Prior to 2001, the top rate with the GST was just under 80 percent. The GST will return to its pre-2001 levels along with the estate tax in 2011.

A Third Layer of Estate Taxation: Taxes on Savings or Labor. The GST is not the only additional tax that can be levied on an estate. Consider the tax penalty imposed on additional earnings of a couple near retirement, self-employed, upper-middle income and in the next-to-the-top rate tax bracket (33 percent bracket). Such a couple might have a farm or business large enough to be subject to the estate tax, even though their additional earnings might still be low enough to be subject to the payroll tax. If they were to work an extra year just to add to their estate, the combined taxes on their earnings would be prohibitively high. In 2009, a worker in the current 33 percent bracket faced tax rates of over 72 percent – nearly 85 percent with GST. [See the figure.]

But in 2011 these rates are scheduled to rebound to pre-2001 levels. Prior to EGTRRA, their federal income tax rate would have been 36 percent. Their combined federal and state income, payroll, and eventual estate tax rates could have easily exceeded 78 percent – or even 90 percent with the GST. A tax rate that high creates an incentive to retire instead of continuing to work or to reinvest interest or dividends in an estate.

Economic and Fiscal Effects of the Estate Tax. Of all the taxes in the U.S. tax system, the estate tax probably does the most damage to output and income per dollar of revenue raised. The high rates discourage saving and investment at the margin, while the base amount that is exempted from the tax reduces the average tax rate and tax revenues. A tax with a large difference between its average and marginal rates does far more damage per dollar of revenue raised than a lower rate on a broader base.

If estate tax rates revert to pre-2001 levels:

- Private sector output and labor compensation would be cut by $183 billion and $122 billion, respectively.

- Gross domestic product (GDP) would eventually be reduced by $183 billion.

- By contrast, repealing the estate tax entirely would boost labor income by $79 billion and add $119 billion to GDP.

Furthermore, the loss in GDP, wages and other income reduces other tax collections by more than the estate tax brings in – resulting in a net revenue decrease from having the tax. One source of loss comes from giving assets to one's heirs over many years prior to death. Indeed, Professor B. Douglas Bernheim of Stanford University estimates that estate tax avoidance by giving assets to children, most of whom are in lower income tax brackets than their parents, costs more in income tax revenue on the earnings of the assets than the estate tax picks up.

Conclusion. The economy, the pretax and post-tax incomes of workers, savers, and investors, and federal, state, and local revenue would all be higher if the estate tax was eliminated.

Stephen J. Entin is president and executive director of the Institute for Research on the Economics of Taxation in Washington, D.C.