The federal government's strategy to contain the financial meltdown is to fight each fire one-by-one and rebuild the old system pretty much as was: socialize the risks (having the public take the hit when things go south) and privatize the profits (banks earn big fees when the economy generates high investment returns). This treats the symptoms, not the disease, and will leave the country financially weaker.

How the Cards Fell. Lehman Brothers filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy on September 14, 2008, in what may be the largest bankruptcy in the history of the world. Lehman's portfolio was largely stuffed with claims to highly risky real estate and dicey mortgages – commonly referred by the industry and news media as "subprime."

These mortgages were part of a $600 trillion market of complex bundles of mortgage-backed securities called derivatives. The principal rating companies – Standard & Poor's, Fitch and Moody's – rated these mortgages AAA (the highest rating possible) in exchange for large payments and after verifying the mortgages were insured by a large insurer, such as the American International Group, Inc. (AIG).

These mortgages were part of a $600 trillion market of complex bundles of mortgage-backed securities called derivatives. The principal rating companies – Standard & Poor's, Fitch and Moody's – rated these mortgages AAA (the highest rating possible) in exchange for large payments and after verifying the mortgages were insured by a large insurer, such as the American International Group, Inc. (AIG).

In making these investments, Lehman Brothers leveraged itself 31 to 1, meaning that for every dollar of company capital, Lehman borrowed another $30 and invested it all in high-risk securities. With leverage of this magnitude, even a 3 percent loss in the value of assets can wipe out the company's capital (the difference between its assets and debts). Because Lehman's shares were claims to its capital, the perception that its assets had taken more than a 3 percent hit drove the stock from $18 in early September to essentially zero on September 14.

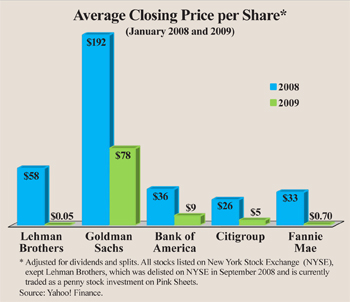

Stock movements of this magnitude hit most financial firms. Consider:

- Goldman Sachs' stock fell 80 percent between its November 2007 peak and its November 2008 nadir.

- Bank of America saw its share price drop from $40 in October 2008 to $3 in March 2009.

- Citigroup, which traded at $24 per share in October 2008, fell dramatically later in the fall and now stands at less than $4 a share.

- Fannie Mae traded at $70 a share in 2007, but by July 15, 2008, had crashed to just $7 a share.

- Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac had borrowed more than $5 trillion and were leveraged 65 to 1.

As the figure shows, during 2008 some of these firms' shares became almost worthless.

Lehman Brothers' crash immediately put pressure on AIG. The reason is not that Lehman owed AIG money, but that the former head of AIG's Financial Products unit and other AIG employees sold large numbers of credit default swaps to Goldman Sachs and other entities. These credit default swaps were insurance policies that covered their purchasers against debt defaults by Lehman and other U.S. and foreign companies, financial as well as nonfinancial.

Therefore, when Lehman went down, AIG had to pay its Lehman insurance claims. More importantly, AIG was immediately forced to post more collateral on many other insurance contracts, which were suddenly understood to be much riskier.

Government Rebuilds the House. AIG was effectively nationalized on September 16, 2008, at a cost of $85 billion to taxpayers. Since AIG's nationalization, the government has engaged in a massive and potentially more expensive policy. The policy entails providing systemic risk insurance to the financial sector – that is, insurance against system-wide collapse. Indeed, the federal government has already handed out, or publicly committed to hand out, more than $12 trillion to the financial sector.

Major components of the $12 trillion bailout include the Treasury's $700 billion Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), the Treasury's $400 billion in actual plus potential pledges of monies to cover Fannie Mae's and Freddie Mac's losses, the Federal Reserve's $301 billion guarantee of Citigroup's troubled assets, nearly $200 billion spent by the Federal Reserve on AIG (with hundreds of billions more likely to come), the $118 billion guarantee of Bank of America's poison securities and the $29 billion spent by the Federal Reserve on Bear Stearns' toxic assets.

The $12 trillion spent by the federal government bailing out the financial sector is close to one year's gross domestic product – that is, the value of all the final goods and services produced by over 130 million Americans working an entire year.

Conclusion. Financial modernity goes far beyond what the old U.S. financial regulatory and rating system can handle. The federal government has bailed out many industries, including banking, mortgage lenders, insurers, money market funds, automakers, credit card issuers, home builders, the states and so on. This invites ongoing gambling at public expense by any business or entity that can reasonably expect a bailout. Moreover, this is a prescription for fiscal insolvency, which could culminate in hyperinflation. Indeed, the United States printed more money between January 2008 and June 2009 than was printed in the entire history of the country (just under $1 trillion).

Systematic reform of the U.S. financial sector is critical. Along with the financial market meltdown, trust in a system that routinely borrows short and lends long, guaranteeing repayment yet investing at risk, has evaporated and will not be regained. What is needed is a system that doesn't gamble with the taxpayers' chips, but instead lets the public make their own risk-taking decisions based on securities that are transparent and whose properties are fully disclosed.

Laurence J. Kotlikoff is an economics professor at Boston University and a senior fellow with the National Center for Policy Analysis. This article is adapted from his forthcoming book, Jimmy Stewart Is Dead: Ending the World's Ongoing Financial Plague with Limited Purpose Banking.