In order to prevent a one-fifth drop in the fees physicians receive under Medicare, Congress is proposing another in a series of temporary fixes. The American Medical Association (AMA) engaged in an expensive lobbying campaign to implement the so-called "doc fix" for Medicare Part B, but Congress is unlikely to permanently solve the problem.

The Sustainable Growth Rate. Since 1997, the federal government has attempted to limit the total growth of Medicare spending for physicians' fees (Part B) to what is called the sustainable growth rate. The rate is determined by the annual growth in real gross domestic product (GDP) and determines how much the federal government will reimburse physicians for services.

Physicians oppose the use of the sustainable growth rate because the cost of providing medical services has been increasing faster than GDP. Thus, this adjustment is basically guaranteed to reduce the doctors' reimbursements. However, physicians have successfully lobbied for short-term "fixes," which temporarily put off the required cuts. Unfortunately, every time Congress temporarily fixes the fee schedule, the gap between fees calculated using the sustainable growth rate and where Congress actually sets them grows wider. As a result, future cuts in fees will need to be more drastic.

Physicians, of course, would like a permanent "fix" – allowing their fees to grow in line with the Medicare Economic Index, a measure of medical cost inflation. This is unlikely to happen. Having the government reimburse physicians on a "cost-plus" basis – like defense contractors – would create more incentives to drive up costs.

Furthermore, a permanent fee "fix" would force Congress to tell the truth about how high the future costs of Medicare are likely to rise. This it is unwilling to do, as it proved during the passage of health reform legislation.

Congress promised a long-term fix of physicians' fees in the first iteration of the health reform law, H.R. 3200. One of the key problems with H.R. 3200, however, was the Congressional Budget Office's conclusion that it would increase the federal budget deficit by $239 billion over the first 10 years. H.R. 3200's long-term "doc fix," which replaced the sustainable growth rate with an inflation-based update, would have accounted for $245 billion of the bill's total cost. Because a deficit-increasing bill violated a presidential promise (namely, that the reform would not increase the deficit), the final legislation scrubbed the doc fix and left it to be intermittently fixed in other legislation.

The House of Representatives passed a resolution on May 28 to delay a scheduled 21 percent cut in Medicare physician payments through 2011, but because the Senate did not vote on the issue before the Memorial Day holiday, the cut officially went into effect on June 1. Currently, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is asking all physicians to wait to bill Medicare in order to give the Senate more time to approve the bill passed in the House.

Organized Medicine's Campaign to Fix Fees. The AMA favors the increase in Medicare payment rates. Indeed, on June 3 it launched a multimillion dollar advertising campaign attacking the Senate for taking a "vacation" over the Memorial Day weekend, instead of fixing the problem of scheduled fee cuts.

Organized Medicine's Campaign to Fix Fees. The AMA favors the increase in Medicare payment rates. Indeed, on June 3 it launched a multimillion dollar advertising campaign attacking the Senate for taking a "vacation" over the Memorial Day weekend, instead of fixing the problem of scheduled fee cuts.

However, the AMA has a vested interest in having the federal government continue to set fees. This is largely because the AMA's core business is selling intellectual property pertaining to the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT©), to which it owns the copyright. CPTs are codes for medical procedures developed by the AMA and used for Medicare and all state Medicaid billing.

In other words, the AMA is a monopolistic supplier of codes that physicians need to submit claims to government-run health care plans. As long as this is its business model, the AMA will never advocate that the government stop fixing physicians' fees. As a monopolist, the AMA prefers to have the government fix (set) prices, rather than have the medical market set fees competitively. The AMA has every right to protect its business interests, but the Medicare crisis is too far gone to allow those interests to block real reform.

Consequences of Falling Medicare Reimbursement Rates. Despite past short-term fee fixes, Medicare beneficiaries' access to care is still tenuous. For example, last October the Mayo Clinic decided that it could no longer accept Medicare patients at its two primary care clinics in Phoenix.

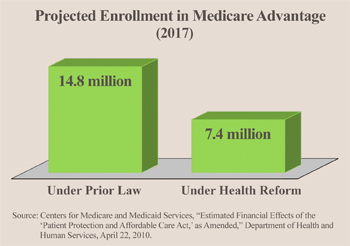

Additionally, in 2009, Houston's largest medical practice – the Kelsey-Seybold Clinic – announced it would no longer accept new patients enrolled in the traditional Medicare Part B program because reimbursements had become too low. Almost all of the clinic's patients have switched to Medicare Advantage plans, most of which negotiate their own payment rates with providers. Unfortunately, many seniors who have access to Medicare Advantage plans will soon lose them under the health reform law, because of a roll-back in the premiums the government will pay the plans and despite the government's insistence to the contrary. In fact, the Chief Actuary of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services estimates that 7.4 million Medicare beneficiaries will lose their Medicare Advantage plans by 2017. [See the figure.]

Conclusion. The fundamental problem with Medicare's fees is not the level at which the government fixes them, but that the government fixes them at all. The system cannot be repaired: It would be far better for the federal government to simply pull the plug on the entire mechanism and convert Medicare Part B to a system of vouchers. In return for a hard budget cap, the government would allow physicians to charge whatever fees they and their patients agreed upon. The government could liberalize the popular, private Medigap plans to allow seniors to cover extra physicians' fees, protecting them from the costs of outpatient care beyond the value of the vouchers.

John R. Graham is Director of Health Care Studies at the Pacific Research Institute.