Many people are worried about the United States' federal budget deficit and accumulating debt burden. In 2009 the federal budget deficit reached a record $1.4 trillion, and public debt (U.S. Treasury securities held by institutions and individuals outside the federal government) is currently more than $8 trillion and growing.

The level of discourse is usually simple: "We're going bankrupt!" But what is the specific threat that the federal government's huge debt burden poses?

Of the three potential effects of the budget deficit and growing public debt – inflation, a debt crisis, or tax hikes – higher taxes leading to slower growth is the most likely consequence.

Potential Effect: Inflation. Budget deficits are only inflationary if the central bank accommodates the deficit and buys back the debt with newly printed money.

Potential Effect: Inflation. Budget deficits are only inflationary if the central bank accommodates the deficit and buys back the debt with newly printed money.

The crucial question is whether the Federal Reserve (or Fed), will stick with the anti-inflation doctrine started in the 1980s or whether they will help the Treasury by inflating the currency. Inflation helps the Treasury by lowering the real (inflation-adjusted) amount of the debt. This is typically done in countries where the central bank is controlled by the government. The U.S. Federal Reserve, in contrast, has substantial independence.

Recently, the Fed has radically increased the monetary base, also called high-powered money. This consists primarily of bank reserves at the Fed. However, the link between the monetary base and the money supply (which includes currency in circulation as well as checking accounts and savings accounts) is looser than historic norms. Think of a car with a slipping clutch. The motor is revving up, but the axle is moving slowly. One fear is that the clutch will suddenly take hold, and then we are off on a wild ride.

If the Fed tightens the money supply by pulling bank reserves out of the system it can prevent inflationary pressures. This requires a delicate not-too-much, not-too-little balancing act, however.

Potential Effect: Debt Crisis. When a country is in a debt crisis, it runs a large deficit year after year. In addition to new borrowing each year, the country must refinance old debt coming due. The country's creditors start to get nervous about the country's ability (or willingness) to repay the debt. As a result, creditors demand higher interest rates and may offer to buy debt only if it is denominated in some other currency.

There are two signs that a country is entering a crisis: 1) the interest rate it has to pay on its debt rises and 2) lenders are not interested in bonds denominated in the country's own currency. Neither seems to be of issue for the United States. Indeed, investors bid $4.63 for every $1 the Treasury was selling at its July 12 auction. (A total of $30 billion in Treasury bills was sold at the auction.) In addition, the International Monetary Fund reports that approximately 61 percent of foreign bank reserves are denominated in U.S. dollars.

In summary, a U.S. debt crisis is not likely.

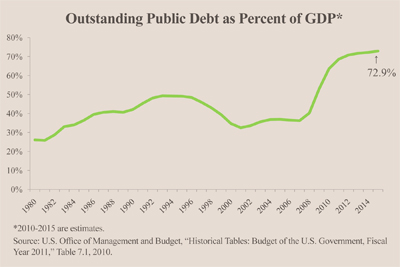

Potential Effect: Higher Taxes Leading to Slower Growth. The result of continued deficits is that the federal debt continues to grow. Carmen Reinhart of the University of Maryland and Kenneth Rogoff of Harvard University have studied financial crises around the world, and find that when the debt to gross domestic product (GDP) ratio reaches 90 percent, "median growth rates fall 1 percent, and average growth falls considerably more." With the United States' debt to GDP ratio closing in on 90 percent, America may well anticipate slower growth. [See the figure.]

Congress and the White House may decide to trim some spending to help lower the debt to GDP ratio, but most expenditures are for entitlements. Here's a rough sketch of the 2015 planned expenditures:

- Interest will total approximately $571 billion.

- Other costs not part of entitlement programs or interest will be about $1.8 trillion.

- Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid will total about $2 trillion.

- Total outlays in 2015 will be approximately $4.4 trillion.

Entitlement services make up nearly half of Congress' planned spending. Cutting costs in this area would lower the debt to GDP ratio considerably, but Congress is not likely "take away" entitlement services from people who are used to receiving them. Therefore, taxes must rise in order to avoid a debt crisis.

A value-added tax (VAT) is being discussed in some corners. But the political roadblocks to a VAT are high: conservatives are afraid that it will be a money machine for government, while liberals worry about the VAT's impact on lower income families.

If the VAT is unlikely, then personal income taxes will have to increase. But, as Arthur Laffer showed, tax rates can be so high that tax revenues decline. This is because higher income taxes create a disincentive for work and investment. As a result, higher income taxes will stifle labor and investment, slowing down income growth.

Conclusion. The bottom line is that we should expect weaker economic growth in the coming decade or two. The United States will look more like Europe, where higher marginal tax rates encourage people to work fewer hours and take longer vacations. We just will not be able to afford luxurious vacations. We will also spend more effort gaming the tax code, looking for tax shelters and dreaming up creative ways to avoid taxes.

William B. Conerly is a senior fellow with the National Center for Policy Analysis.