American workers live longer each decade but they continue to retire early. They often begin receiving Social Security benefits, quit working and stop contributing to national output well before age 65. Reversing these trends must be an important objective when designing long-term reforms to balance revenues and expenditures on elderly entitlements.

Chile faced similar problems prior to 1981. It had a traditional pay-as-you-go defined benefit system, like Social Security in the United States. Workers had strong incentives to start their retirement benefits as soon as possible, because postponing pensions and adding contributions did not increase benefits commensurately. Labor force participation dropped dramatically when workers became eligible for pensions.

This changed with reforms in 1981 that replaced the defined benefit system with a defined contribution system. All new workers were required to join the defined contribution system while existing workers had a choice. Most workers are now in the new system and are required to contribute 10 percent of their wages to an individual account. Contributions are invested in a pension fund chosen by the worker and accumulate a market rate of return. Payouts take the form of inflation-protected annuities or gradual withdrawals during retirement. The new system increased incentives for older workers to postpone retirement and continue working. The response was dramatic.

This changed with reforms in 1981 that replaced the defined benefit system with a defined contribution system. All new workers were required to join the defined contribution system while existing workers had a choice. Most workers are now in the new system and are required to contribute 10 percent of their wages to an individual account. Contributions are invested in a pension fund chosen by the worker and accumulate a market rate of return. Payouts take the form of inflation-protected annuities or gradual withdrawals during retirement. The new system increased incentives for older workers to postpone retirement and continue working. The response was dramatic.

Tighter Retirement Preconditions. In the old system, the normal pension age for men was 65, but early benefits were common. The normal pension age in the new system is still 65, but until 1988 early benefits were not permitted. Since 1988 they have been allowed, with tight restrictions:

- A worker's retirement account had to provide a pension that was at least 50 percent of his own average wage and 110 percent of the government-guaranteed minimum benefit.

- Recently these preconditions were raised to 70 percent of the individual's average wage and 150 percent of the minimum benefit.

- The purpose of these strict preconditions is to keep individuals from retiring with too little savings and eventually running out of money or becoming dependent on government aid.

Better Incentives to Continue Working. Receiving one's pension early does not mean early withdrawal from the labor force. Instead, it simply means that workers can stop making mandatory contributions to their retirement accounts and start making withdrawals. Indeed, the new system encourages continued work, as workers get market rates of return for additional contributions and postponed withdrawals.

Once workers begin receiving retirement benefits, they are exempt from making mandatory contributions. In addition, contributions are voluntary after age 65, even for individuals who have not yet begun receiving retirement benefits. This decreases the implicit tax on work posed by mandatory contributions and increases the net wage.

Prior to 1981, government employees could not stay in their jobs once they started to receive retirement benefits. If they wanted to work they had to switch jobs, which was difficult for older workers. The new system allows individuals receiving benefits to continue working with no restrictions or further contributions.

Effects of the Reform. Following the 1981 policy changes and reforms, and after controlling for other sources of change in retirement behavior, the percentage of individuals receiving early benefits fell significantly:

- The proportion who received benefits before age 65 decreased by about 8 percentage points.

- The proportion of individuals who started receiving retirement benefits by their early 60s fell by about a quarter.

- The proportion who started receiving benefits by their 50s was cut in half.

Postponing the commencement of benefits could be due to market returns on additional contributions, which made workers more willing to continue working in order to save more money for retirement. Or it could be due to tighter preconditions on early retirement, which required more individuals to continue working until age 65. Tighter preconditions seem to dominate, as the percentage of individuals who receive benefits after 65 has not changed.

More older workers kept working following the reform, after controlling for other factors:

- Labor force participation rates for individuals in their 50s rose 12 percentage points.

- Labor force rates rose 13 percentage points for those aged 65-70.

- Individuals aged 60-64 increased their labor force participation the most – by 19 percentage points.

The biggest change in labor force participation was for individuals who had started receiving benefits from their retirement accounts:

- Participation rates rose by 15 percentage points for pension recipients in their late 60s.

- Rates rose by 28 percentage points for those in their 50s and early 60s.

- Among all pension recipients under age 70, the proportion who continued working more than doubled.

In contrast, among individuals not receiving pensions, labor force participation rates did not change much until age 65. This suggests that the exemption from mandatory contributions (for all pensioners and nonpensioners over 65) strongly encouraged seniors to continue working.

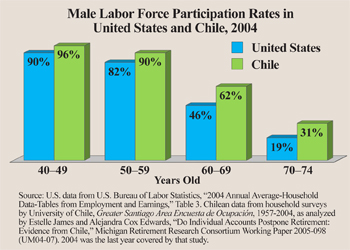

Lessons for the United States. Labor force participation rates of older individuals have been creeping upward in recent years in the United States, but they still lag significantly behind Chile, especially for workers in their 60s and early 70s. [See the figure.] This has important implications for U.S. economic growth – under full employment, more workers means greater production. Moreover, later retirement by U.S. workers would expand the tax base and help ease the financial burden of programs such as Social Security and Medicare. The experience of Chile suggests that this could be encouraged by partially exempting older workers from Social Security and Medicare payroll taxes, and raising the age or other preconditions for early retirement.

Estelle James is a senior fellow with the National Center for Policy Analysis. This article is based on her paper with Alejandra Cox Edwards: "Do Individual Accounts Postpone Retirement: Evidence from Chile?" distributed by the Michigan Retirement Research Center.