Disability costs are rising in many countries, including the United States. Disability is the fastest-rising component of U.S. Social Security, growing at nearly twice the rate of retirement benefit spending. Chile, however, reversed this trend when it implemented a new retirement and disability benefits system in 1981.

Chile's Integrated Retirement and Disability System. In the United States, current workers pay taxes to fund the benefits of today's retired and disabled workers. Under the Chilean system adopted in 1981, workers prefund their retirement with individual accounts that are invested by private pension companies and earn market rates of return. The accounts are also used to partially fund disability and survivors' benefits for workers who have not reached retirement.

Additionally, each pension company is required to provide group disability and survivors' insurance for its affiliated workers. Until 2009 these insurance costs were included in the general fees that pension funds charged workers.

Disabled workers were guaranteed a defined benefit for the remainder of their lives: 70 percent of their average wage if totally disabled or 50 percent if partially disabled. In the long run, workers' savings were projected to cover about 50 percent of their disability benefits. Widows and children of covered workers also got a defined benefit. The group policy made up any difference between the person's account funds and the amount needed to finance the promised benefits.

Disabled workers were guaranteed a defined benefit for the remainder of their lives: 70 percent of their average wage if totally disabled or 50 percent if partially disabled. In the long run, workers' savings were projected to cover about 50 percent of their disability benefits. Widows and children of covered workers also got a defined benefit. The group policy made up any difference between the person's account funds and the amount needed to finance the promised benefits.

Benefits of the Chilean System. Because each pension fund paid for the disability and survivors' insurance of its affiliated workers, it had a financial incentive to choose a low-cost insurance company and contest questionable claims. Decisions on claims were made by medical boards appointed by a public agency, but pension funds participated by providing information, asking questions, bringing appeals and helping establish objective medical criteria for qualifying as disabled. This weeded out weak cases and discouraged workers from making dubious claims. Indeed, post-1981 disability recipients tend to have more serious medical conditions (measured by their subsequent mortality rate) than did pre-1981 recipients. In this sense, the new system targeted the medically disabled more accurately. In the United States, by contrast, disability determinations are made by government agencies with no direct financial interest in the outcome.

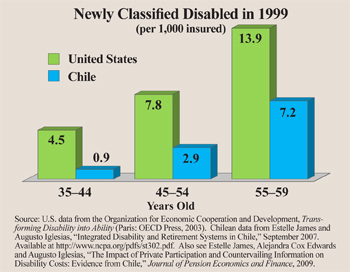

As a result of this process and other factors, the disability rate among Chilean workers fell significantly after 1981 and is now less than half that in the United States, after controlling for age:

- Workers in the new Chilean system are only 21 percent to 35 percent as likely to start a disability pension as they were in the old system, after controlling for age and gender.

- In 1999, among 45- to 54-year-olds, 2.9 per thousand covered members of the new system in Chile were accepted to newly disabled status, compared to 7.8 per thousand in the United States.

- For 55- to 59-year olds, these numbers were 7.2 per thousand in Chile, compared to 13.9 per thousand in the United States. [See the figure.]

Problems with the Chilean System. The new system posed some troublesome equity problems. For example, it gave pension companies a financial incentive to try to attract workers with lower disability risks and discourage high-risk workers from affiliating with them. Since insurance costs were ultimately passed on to workers through fees, two workers with the same risk profile might pay different implicit premiums depending on their pension company.

Furthermore, women were required to pay the same insurance rates as men, but got lower expected benefits because they were less likely to die young or become disabled.

Recent Changes to the Disability System. In 2008 Chile made significant reforms to its disability system. Payments continue to be largely prefunded, but the pension companies are now required to collectively purchase disability coverage through a single public auction at which private insurance companies bid to cover all workers. Therefore, all pension companies pay the same premiums regardless of their separate claims experience. This creates scale economies in bargaining with insurance companies and eliminates the incentive for pension companies to attract low-risk workers. However, it also eliminates the incentive to dispute questionable claims, which could add to costs.

In addition, the insurance fee will now be paid by employers, rather than workers. Shifting insurance payments will, in the short run, increase labor costs and may reduce employment. In the long run, the cost will likely be passed to workers in the nontransparent form of lower wages. The cost, and negative impact on wages, will grow as the workforce ages.

In the future, women will get increased benefits. Insurance fees will be based on the experience of men, but women will get a rebate into their retirement accounts equal to the difference between actual male and female disability rates, thereby raising their pensions. Additionally, women who work between ages 60 and 65 will continue to be covered by disability insurance (previously benefits for women stopped at age 60).

At the first public auction in 2009:

- The Ministry of Finance estimated that insurance costs would rise from 1 percent to 1.2 percent of wages due to the increased benefits to women.

- Yet, actual costs as determined by the public auction are now 1.88 percent of wages – 57 percent higher than projected and 88 percent higher than in the past.

- A rebate of 0.2 percent of wages will be put into women's accounts, but the net charge to women and men will rise.

Much of these higher fees appear to be attributable to the new process, which reduces incentives for pension companies to control disability rates and costs.

Conclusion. Chile's experience demonstrates that disability benefit costs can be contained by the participation of private parties that have a direct financial interest in deterring questionable claims. Equally important, this can result in more accurate targeting of disability benefits. While Chile implemented this process in a funded defined contribution context, it could also be adapted for use in other countries that have more traditional pay-as-you-go disability schemes, like the United States.

Estelle James is a senior fellow with the National Center for Policy Analysis.