On September 23, 2010, a wide array of provisions from the controversial new Obama health care law went into effect, creating new restrictions on existing health insurance plans and an even bigger set of restrictions on new health plans.

Perhaps the most immediate and far-reaching impact will be felt by the two million Americans who currently have limited medical benefit plans, known colloquially as "mini-med plans."

How Mini-Med Plans Work. Mini-med plans have gained popularity in recent years, especially among companies that employ low-wage, seasonal and part-time workers, and contractors. Mini-meds allow these employers to offer a health plan at a low cost to both the company and employees. Premiums for these plans generally range from $20 to $190 per month for single coverage and $100 to $500 a month for family coverage. They offer basic benefits, such as a prescription drug discount card, and coverage for doctors' visits and lab tests. Deductibles and copays are also low, and some mini-meds provide first-dollar coverage for some services (such as wellness visits), so there is no out-of-pocket cost before the benefits become accessible. Among companies that offer mini-med plans are McDonald's and Waste Management.

How Mini-Med Plans Work. Mini-med plans have gained popularity in recent years, especially among companies that employ low-wage, seasonal and part-time workers, and contractors. Mini-meds allow these employers to offer a health plan at a low cost to both the company and employees. Premiums for these plans generally range from $20 to $190 per month for single coverage and $100 to $500 a month for family coverage. They offer basic benefits, such as a prescription drug discount card, and coverage for doctors' visits and lab tests. Deductibles and copays are also low, and some mini-meds provide first-dollar coverage for some services (such as wellness visits), so there is no out-of-pocket cost before the benefits become accessible. Among companies that offer mini-med plans are McDonald's and Waste Management.

Mini-Med Plans Are Affordable. Despite harsh criticism from official circles, the mini-meds' popularity has soared over the past several years, providing an affordable route for some corporations to offer health insurance. This has been particularly true as major medical plans have become more expensive. The mini-meds' lower costs provide an appealing alternative, especially for low-wage workers.

But the reason the mini-meds are so affordable is exactly the same reason they are in danger of extinction under the reformed health insurance system. The plans are defined by their low annual limits on benefits. These limits are well below the new federally mandated limits. The new law requires conventional health insurance policies and employer-sponsored health plans to increase their annual limits on coverage to $750,000. The cap will continue to rise in subsequent years. Eventually, there will be no annual or lifetime coverage limits.

Mini-Med Plans Under Health Reform. Many of these mini-med plans would have immediately ceased operation under the new health reform law. But in many cases, these plans are the only kind of policy that employers could afford, given the low productivity of their employees. To regulate these people out of their insurance outright would have been embarrassing – especially in light of the revelation that more than 100,000 McDonald's workers could lose their health plan – right on the eve of a national election. So the bureaucrats did what bureaucrats do so well – they added another layer of sloppy regulation on top.

There is a provision for a waiver program for the existing mini-meds, allowing the companies that sell them to petition the Office of Consumer Information and Insurance Oversight (OCIIO) to ask permission to continue to insure these people under the terms of their plans. Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius has already granted one-year waivers to plans covering a million workers (including McDonald's).

If this sounds bad on the surface, the reality is much worse. The petitioning process is ill-defined, and there is no legal standard at all for granting the waivers themselves. Asking for such waivers is a crapshoot, dependent on the whims of bureaucrats. In any event, the waivers will expire in 2014, when employer-sponsored health plans cannot legally have annual or lifetime limits.

What Will Happen to Mini-Med Plans? The end result is, and likely was always intended to be, that the mini-med plans, derided by the government but embraced by the market, will become harder to keep and virtually impossible to replace. Far from providing Americans with affordable health insurance, the health reform plan is mortally wounding one of the last sources of such insurance. The ironic effect of a law that President Obama said would extend insurance to the uninsured is to make insurance for low-income Americans less affordable and, therefore, cause many of them to go without insurance.

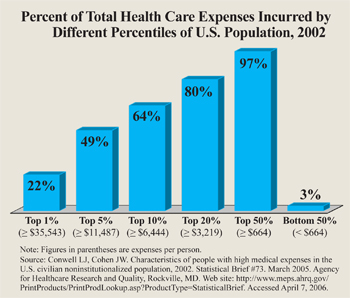

Advocates of the health reform bill may claim that this is for the best, and that the low annual limits are a serious handicap. It is true that the ideal insurance is catastrophic insurance. Yet, the value of the mini-meds is underrated. Most Americans covered by health insurance have very low claims experience in any single year and so the mini-meds are at least worth something. [See the figure.] And for very low-income Americans, a few thousand dollars in medical expenses, though not catastrophic, are a serious hit and, therefore, are worth insuring against.

Furthermore, having such a plan is not just about what is paid out, but also its ability to get discounts at in-network hospitals. Often the savings on a major procedure over the retail price will be greater than the payment the company actually makes, and that is a savings that is all the more crucial for low-income Americans than for those who are better off.

Conclusion. The mini-meds cannot promise absolute coverage in the case of catastrophic health problems, and they were never intended to. That's one problem with such plans. But which is worse: having insurance that doesn't cover all catastrophic expenses or having no insurance at all?

David R. Henderson is a research fellow with the Hoover Institution and an economics professor at the Naval Postgraduate School.