Investment spending has been sluggish in spite of record low interest rates and enormous levels of excess reserves in the banking system. Banks have been criticized for not lending enough, but the real problem is that not enough businesses want to borrow.

Businesses are hesitant because the expected after-tax returns on added capital are too low to make adding to the capital stock worthwhile. Instead of easier money, we need higher after-tax returns to capital to create investment and growth.

Thus, lower taxes on investments allow more capital to be created and employed. Permanent expensing fits the need and is consistent with real tax reform.

Thus, lower taxes on investments allow more capital to be created and employed. Permanent expensing fits the need and is consistent with real tax reform.

Expensing versus Depreciation. The federal individual and corporate income tax typically requires businesses to depreciate their investments in plant, equipment and other buildings over many years. Depreciation means that a business cannot deduct from that year's taxable income the full cost of the investment, but must write it off over a number of years, according to a fixed schedule. As a result of this delay, business income is overstated and overtaxed.

The present value of a dollar written off in the future is worth less than a dollar write-off today. Consider:

- A dollar spent on a seven-year asset gets a write-off worth only $0.91 cents in present value (if inflation is zero).

- A dollar spent on a building (written off over 39 years) gets a deduction worth just $0.55 cents in present value.

- The cost of the delay rises with the inflation rate – for example, at a 5 percent inflation rate, the seven-year asset's write-off is worth only $0.81 and the building's write-off value drops to $0.30.

Indeed, even at modest inflation rates, the overstatement of business income by depreciation can cut the rate of return on investment in half. For example, take a machine that costs $100 today and returns $115 in sales over its life. It returns a $15 profit (in present value). If allowed an immediate $100 write-off for tax purposes, the firm's taxable profit is also $15. At a 33 percent tax rate, its tax is $5 and after-tax income is $10, for a 10 percent total return.

Suppose the firm is allowed a slower write-off worth only $85 in present value. Its (inflated) income for tax purposes will be $30, tax is $10 and net real after-tax income is only $5 – a 5 percent return. Requiring depreciation has cut the return in half.

Temporary versus Permanent Expensing. The effect on investment and the economy depends on whether expensing is permanent or temporary. Permanent expensing results in a permanent increase in capital creation, which also raises employment and wages. Temporary expensing makes it worthwhile for businesses to hasten investment to take advantage of the better tax treatment. But that means less investment in the year after the provision expires, and no permanent increase in the quantity of capital created and employed. Temporarily allowing businesses and individuals to expense (immediately write-off) business investments would boost near-term spending, but much of this increase would be in the form of a step up in construction and capital purchases that were already planned for future years- with no net gain. By contrast, permanent expensing would encourage additional capital formation, and raise labor productivity, wages and employment thereafter.

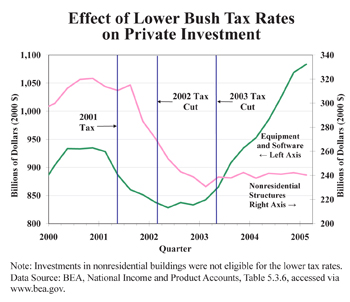

Evidence from the Bush Tax Cuts. The 2001 Bush tax cuts were intended to fight the 2001 recession. Unfortunately, they did next to nothing to reduce the tax burden on capital formation in 2001 and 2002. [See the figure.] Thus, investment in equipment and buildings declined, even after gross domestic product resumed slow upward movement.

In 2002, Congress enacted a 30 percent expensing provision, intended to counter the slump in equipment spending. Equipment spending leveled off soon after the provision was enacted. Spending on nonresidential business structures, which were not eligible for the faster write-off, continued to fall.

In 2003, Congress raised the expensing percentage to 50 percent, and reduced the top rate on capital gains and dividends to 15 percent. The bill also accelerated the remaining marginal income tax rate reductions being phased in under the 2001 tax act. As the figure indicates, equipment spending began to soar after the 2003 tax cut was enacted. Spending on structures leveled off and rose slightly, spurred by the lower capital gains, dividend and marginal income tax rates on investors.

Is Expensing Too Generous? Temporary expensing accelerates cost recovery and reduces tax revenue in the near term, but recoups the revenue in later years when businesses have no further cost to report. Permanent expensing has minimal annual static revenue loss long-term, and should raise revenue over time due to added growth.

Some tax analysts contend that expensing can lead to negative tax rates if businesses borrow money to purchase equipment. The business gets a deduction for interest paid on the loan, as well as a deduction for the investment itself. However, this analysis is incomplete. Tax-deductible interest paid by the borrower is taxable income to the lender. The result is a revenue wash to the Treasury.

Conclusion. If Congress and the Obama administration do not extend the 2003 tax reforms, further economic slowdown is likely. Raising expensing from 50 percent to 100 percent would increase the after-tax return on capital by about 2.5 percentage points. That alone, if permanent, would boost investment. It is critical that it be accompanied by extending the 15 percent tax rate caps for dividends and capital gains. Otherwise, the improvement from expensing would be wiped out twice over.

Permanently higher investment and a larger capital stock require a permanent improvement in the tax treatment of capital income. Happily, what is right for the long-term would also help in the short-term.

Stephen J. Entin is president and executive director of the Institute for Research on the Economics of Taxation in Washington, D.C.