The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) is expected to add up to 16 million more Medicaid enrollees and will significantly expand eligibility for families with incomes up to 133 percent of the federal poverty level. The PPACA requires states to streamline their enrollment process – making it easier for eligible populations to enroll and retain Medicaid coverage.

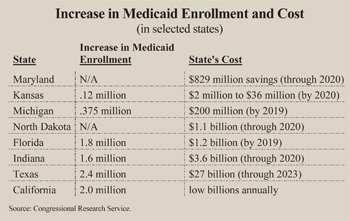

Initially, the federal government will pay 100 percent of the cost of the newly eligible, newly enrolled populations and 95 percent of costs through 2019. However, there are hidden costs that will strain state budgets. [See the figure.]

Problem: The Cost of Enrolling the Already Eligible. According to various estimates, there are 10 million to 13 million uninsured people who are already eligible for Medicaid – but not enrolled. When the individual mandate to obtain health coverage takes effect in 2014, many of the uninsured are likely to be swept up in outreach efforts. Although the cost of enrolling newly eligible individuals will be paid by the federal government, the cost of covering those previously eligible for Medicaid must be paid for under the current federal matching formula. Many states will find the cost of their Medicaid programs higher as a result.

Problem: The Cost of Enrolling the Already Eligible. According to various estimates, there are 10 million to 13 million uninsured people who are already eligible for Medicaid – but not enrolled. When the individual mandate to obtain health coverage takes effect in 2014, many of the uninsured are likely to be swept up in outreach efforts. Although the cost of enrolling newly eligible individuals will be paid by the federal government, the cost of covering those previously eligible for Medicaid must be paid for under the current federal matching formula. Many states will find the cost of their Medicaid programs higher as a result.

For example, a decade after the PPACA's implementation, Texas Medicaid rolls are predicted by the Texas Department of Health and Human Services to rise by 2.4 million people. Of these, only 1.5 million enrollees will be newly eligible. About 824,000 individuals will be those previously eligible but not enrolled. The federal government will contribute a much smaller share of the cost of these previously eligible enrollees compared to newly eligible enrollees.

Problem: Low Medicaid Provider Payments. On the average, reimbursements for Medicaid providers are only about 59 percent of what a private insurer would pay for the same service, but it varies from state-to-state. For example:

- New York pays primary care physicians only about 29 percent of what private insurers pay for primary care.

- The comparable figure in New Jersey is 33 percent.

- California pays primary care providers 38 percent of what private insurers pay.

- Texas reimburses primary care physicians for about 55 percent of what private insures pay.

Low provider reimbursement rates make it more difficult for Medicaid enrollees to find physicians willing to treat them compared to privately insured individuals. States will bear much of the cost of keeping Medicaid provider fees at a level necessary to ensure enough physicians are willing to participate in the program. States with historically low reimbursement rates, such as New York state and New Jersey, will be hardest hit. In Texas, which is near the national average, the cost of maintaining higher Medicaid reimbursements will start at $500 million in 2016 – rising to $1 billion annually by 2023.

The PPACA provides funding that will temporarily raise primary care provider reimbursements to the same level as Medicare payments, which pays health care providers an average of 81 percent of what private insurers pay. But the federal government will only fund this provision for two years (2014 and 2015). If states truly want their Medicaid enrollees to have access to quality medical care, they will have no choice but to increase provider reimbursements on par with Medicare.

Problem: Lower Payment to Safety Net Hospitals. Disproportionate share hospital (DSH) payments are used to compensate hospitals that treat a disproportionate share of indigent and uninsured patients. Some of these patients enter the hospital through the emergency room, while others are referred by physicians. In total, the federal government distributes about $12 billion annually to help hospitals that treat indigent patients offset part of the cost.

The PPACA reduces DSH payments by about one-quarter through 2020. Beginning in 2018, annual reductions are about $5 billion per year. The rationale is that as more patients have coverage, hospitals will have fewer uninsured patients. However, 23 million people will remain uninsured – some of whom may seek uncompensated care. Hospitals do not have the means to determine whether their future case mix will include the newly insured or those who have fallen through the cracks. States may have to bear some of the additional costs if their hospitals are to stay solvent.

Problem: Crowd Out of Private Insurance. Many of the newly insured under Medicaid will likely be those who previously had private coverage. Research dating back to the 1990s consistently confirms that when Medicaid eligibility is expanded, 50 percent to 75 percent of the newly enrolled are those who have dropped private coverage. In addition, a 2007 analysis by MIT economist Jonathan Gruber, found, on average, about 60 percent of newly enrolled children in State Children's Health Insurance Program were previously covered privately. Thus, it is reasonable to conclude that much of the increase in Medicaid rolls will be individuals who were previously privately insured, meaning the number of uninsured will not fall as expected.

Conclusion. Although the federal government will pay much of the costs, states will still find their share unaffordable.

Devon Herrick is a senior fellow with the National Center for Policy Analysis.