The scope of emergency services local governments provide has expanded over the years from fire fighting and rescue to providing advanced medical care, transport and a point-of-access to the health system. As a result, emergency medical services (EMS) have become more costly.

An estimated 32 million to 34 million individuals will gain public or private health insurance under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). Insured individuals consume nearly twice as much health care as the uninsured, on the average. Thus, EMS utilization will likely increase; however, the ACA does not provide funds to pay for increased EMS use. This will force local governments to choose between raising taxes, finding alternative revenue sources or reducing emergency services.

Use of Emergency Medical Services. Ambulance trips to hospitals have grown 13 percent from 1997 to 2006, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In 2006, the 18.4 million ambulance transports to hospitals accounted for 15.4 percent of emergency department visits.

Research has shown that the number and frequency of emergency room (emergency department) visits is associated with insurance status:

- The rate of emergency room use is higher for Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries than for the uninsured and individuals with private insurance.

- A Medicaid enrollee is more likely than a privately insured or uninsured individual to visit the emergency room and also more likely to use it multiple times in a year, according to the National Center for Health Statistics.

- Assuming that half of the 32 million to 34 million newly insured under the ACA gain private coverage and half will be enrolled in Medicaid, the NCPA estimates that they will generate 848,000 to 901,000 additional emergency room visits every year.

Medicare and Medicaid enrollees disproportionately use emergency services compared to the privately insured, perhaps because they have less access to primary care providers. In addition, elderly Medicare recipients and low-income Medicaid enrollees are less likely to have independent means of transportation, making ambulance use more likely.

How EMS Is Funded. Reimbursement from public and private insurers is a major source of revenue for fire and ambulance departments, but the primary source of funding is property taxes. Budget restraints, decreasing property values and restrictions on the use of municipal bonds to pay for equipment will make it difficult for many communities to increase their financial support.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has created a national ambulance fee schedule in an attempt to standardize billing across the spectrum of insurance status. Over the past five years, many states have adopted it. However, since the national fee schedule does not cover the actual cost of the services provided, EMS services are subsidized by local taxpayers. A number of communities bill the uninsured for the EMS services they use, but it is difficult to collect. The only alternative may be local tax increases.

Medicare Payments for Ambulance Services. On average, EMS agencies lose money responding to calls from the publicly insured. For example:

- The ACA will increase Medicare Part B reimbursements for urban-based transport by 3 percent, but only for one year (2011).

- Adjusted for the 3 percent increase, Medicare will reimburse providers $249.61 (plus an additional $6.87 per mile in urban locations) for basic transport in the state of Texas.

- Nationally, however, the cost of transporting an individual to the emergency room by ambulance ranged from $99 to $1,218 per trip and averaged $415, according to a 2007 Government Accountability Office report.

Thus, EMS agencies are not reimbursed for the full cost of Medicare transport, and local taxpayers are stuck with the difference.

Furthermore, ambulance providers are generally not compensated for care unless an individual is actually transported. Thus, even if the ambulance is only called as a precaution, or an individual's medical needs can be met at their location, there is a financial incentive to take an individual to a hospital in order to receive reimbursement.

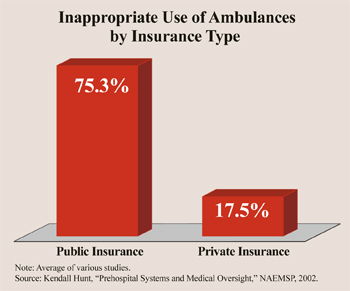

A 2006 report by the Office of the Inspector General estimates that Medicare spent $3 billion for ambulance transports in 2002. More importantly, the Inspector General found that one-fourth of ambulance transportation for the publicly insured did not meet Medicare requirements, resulting in $402 million in improper payments. Researchers estimate that the rate of inappropriate ambulance use by the publicly insured ranges from 59 percent to 85 percent, compared to only 13 percent to 22 percent of privately insured individuals. [See the figure.]

Inappropriate use in this context is defined as services provided by an emergency agency to an individual when there is a safe alternative to ambulance transportation. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid say ambulance use is a medical necessity "where the use of other methods of transportation is contraindicated by the individual's condition."

Increasing the number of individuals who qualify for public insurance will only exacerbate the problem.

Conclusion. Scaling back emergency services would limit our national preparedness to respond to all incidents, but fragmented and inadequate financing risks municipal insolvency. Federal reimbursement rates do not cover EMS costs and the increased demand due to the ACA will put additional stress on the system. Possible solutions include dedicated taxes and changes in health insurance reimbursement policies that give patients incentives to control their consumption and cost, and reimburse EMS providers for medical treatment that does not require transport.

Peter A. Swanson is a Hatton W. Sumners Scholar at the National Center for Policy Analysis, a National Registered Emergency Medical Technician and holds EMT certifications in Texas and New York state.