The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) continues to expand its reach, creating a host of new regulations at a high cost to the economy. This is especially true of two new EPA initiatives: a proposed revision to the national ground-level ozone standard and the attempt to regulate greenhouse gas emissions under the Clean Air Act.

Stricter Ozone Standards. The EPA is proposing a new, more restrictive primary ozone standard under the National Ambient Air Quality Standards program, which regulates air pollutants the EPA deems unhealthy. Ozone is formed by a combination of other regulated pollutants, such as nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds. Thus, in order to reduce ozone levels, areas violating the new standard will have to reduce emissions from sources that emit components of ozone — such as vehicles, industrial facilities and electric utilities.

The current primary standard — set in 2008 and not yet implemented — is 0.075 parts per million (ppm), based on an eight-hour average of measurements by air monitors. The EPA suspended implementation of the current standard in 2009 to ensure that it had a solid scientific base. Based on its review, the EPA decided to set a new standard somewhere between 0.060 ppm to 0.070 ppm (also based on an eight-hour average). Finalization of the new standard has been delayed several times and no firm date has been set for a decision.

The current primary standard — set in 2008 and not yet implemented — is 0.075 parts per million (ppm), based on an eight-hour average of measurements by air monitors. The EPA suspended implementation of the current standard in 2009 to ensure that it had a solid scientific base. Based on its review, the EPA decided to set a new standard somewhere between 0.060 ppm to 0.070 ppm (also based on an eight-hour average). Finalization of the new standard has been delayed several times and no firm date has been set for a decision.

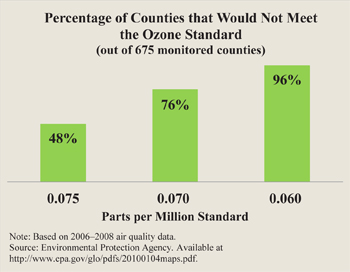

Most monitored counties — many in urban areas — will not meet the new standard. [See the figure.] In fact, up to 76 percent of the 675 U.S. counties where ozone is monitored would not meet a 0.070 ppm standard, according to a 2010 Congressional Research Service report. Up to 96 percent would not meet a 0.060 ppm standard. These so-called non-attainment areas will be subject to additional regulation and EPA oversight, making business expansion difficult and encouraging businesses to move to counties that do attain the standard or to leave the country entirely. Communities in non-attainment areas could also lose federal highway funding.

Estimates vary, but researchers agree that complying with a new ozone standard will be costly. Indeed:

- A 0.070 ppm standard could cause a $14.8 billion decline in production and the loss of 91,700 jobs by 2030 in the Cincinnati-Dayton, Ohio, region alone, according the U.S. Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works.

- Compliance costs could reach $19 billion to $25 billion for a 0.070 ppm standard and $52 billion to $90 billion (in 2006 dollars) for a 0.060 ppm standard by 2020, estimates the EPA.

- Roughly 7.3 million jobs could be lost by 2020 with a 0.060 ppm standard and the present value of the cost of attaining a 0.070 ppm primary standard could exceed $1 trillion, estimates the Manufacturers Alliance for Productivity and Innovation.

The benefits of a stricter ozone standard are questionable. The EPA regulates the ambient amount of ozone, but studies on health effects measure inhaled ozone. Ambient levels are 1.67 to 2.5 times higher than the amount that people inhale, according to Joel Schwartz, an adjunct professor of environmental studies at California State University, Sacramento. Studies have found that exposure to levels up to 0.1275 ppm are safe. Thus, for a person to actually be exposed to a harmful level, ambient ozone would have to be far above the 2009 national average concentration of 0.069 ppm.

Expensive Greenhouse Gas Regulations. Under the Clean Air Act, the EPA is required to regulate emissions of any air pollutant that it determines to be dangerous to public health. A 2007 Supreme Court ruling found that greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide, are pollutants. In December 2009, the EPA published a finding that greenhouse gases are dangerous to public health. As a result, the EPA must begin regulating greenhouse gas emissions, which it had not previously controlled under the Clean Air Act.

Air pollution sources that have the potential to emit more than 100 tons per year of a regulated pollutant must apply for a Title V operating permit. Less than 20,000 pollution sources needed permits in the absence of EPA greenhouse gas regulation. Over time, regulating greenhouse gases as pollutants could increase the number of sources that need operating permits to roughly 6 million.

Studies have found that regulation of greenhouse gases would be very costly. Consider:

- An estimated 476,000 to 1,400,000 jobs would be lost by the end of 2014, according to the American Council for Capital Formation.

- Up to 2.5 million jobs could be lost, the average annual household income could be decreased by $1,200, and gasoline and residential electricity prices would increase by 50 percent by 2030, estimates Management Information Services, Inc., an economic research firm.

- Nearly $7 trillion (in 2008 dollars) in economic output would be lost by 2029, reports the Heritage Foundation.

Unfortunately, the EPA’s efforts will be futile. Even if the entire Western Hemisphere suddenly eliminated all carbon dioxide emissions, the effect on global emissions would likely be offset within a decade by the growth of China’s emissions alone. Indeed, the EPA expects total emissions from developing countries to exceed those from developed countries by 2015, and expects global greenhouse gas emissions to grow until at least 2030.

Conclusion. Affordable energy is a key component of a prosperous economy. Higher energy prices and the loss of over 7 million jobs and billions of dollars of gross domestic product over the next two decades — with no offsetting public health or environmental benefit — will make present and future generations worse, not better, off. Congress should therefore act immediately to stop the EPA before it can further hamper our struggling economy.

Kennedy Meier is a policy intern with the National Center for Policy Analysis.