Restrictions on who can and cannot practice a certain profession have increased significantly in recent years. Occupational licensing — the most onerous restriction — requires people to pass tests and meet other criteria before they can practice a trade. It is a barrier to employment, disproportionately affecting low-income and immigrant workers, and frequently benefitting established practitioners by limiting competition from new entrants.

What Is Occupational Licensing? Three levels of regulation generally control who can work in particular jobs: registration, certification and licensing. Registration usually includes submitting one’s name and contact information for a database. For example, Idaho requires building contractors to register with the state Bureau of Occupational Licensing. Certification means a person has passed an exam on the relevant subject and registered his contact information. In general, people can work in an occupation without being certified, though an employer can demand it. For instance, many car mechanics are certified, but it is not necessary in order to be a mechanic. Licensing typically includes a combination of education, an exam and a licensing fee. It is illegal to operate without a license in licensed industries, such as law and medicine.

What Is Occupational Licensing? Three levels of regulation generally control who can work in particular jobs: registration, certification and licensing. Registration usually includes submitting one’s name and contact information for a database. For example, Idaho requires building contractors to register with the state Bureau of Occupational Licensing. Certification means a person has passed an exam on the relevant subject and registered his contact information. In general, people can work in an occupation without being certified, though an employer can demand it. For instance, many car mechanics are certified, but it is not necessary in order to be a mechanic. Licensing typically includes a combination of education, an exam and a licensing fee. It is illegal to operate without a license in licensed industries, such as law and medicine.

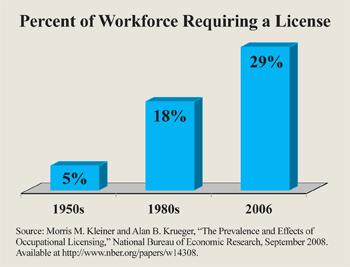

The Rise in Licensing. Licensing has increased dramatically over the last 50 years. According to labor economists Morris M. Kleiner and Alan B. Krueger:

- In the 1950s, less than 5 percent of U.S. workers were in occupations that required a license.

- By the 1980s, that number was almost 18 percent.

- In 2006, 29 percent of workers were in occupations that required a license. [See the figure.]

Why License? Advocates of licensing are typically well-established practitioners of that trade. They have an incentive to reduce the number of competitors and often claim that licensing will safeguard consumers from unqualified providers.

However, there is little evidence that occupational licensing increases product quality. For example:

- The Institute for Justice, a public interest law firm, asked florists to rate the quality of 25 arrangements from licensed florists in Louisiana and 25 arrangements from unlicensed florists in Texas. The judges could detect no difference in quality.

- In 2001, the Canadian Office of Fair Trading looked at 15 academic studies that consider the effects of occupational regulation on product quality and found regulation had a positive impact in just two instances.

Even when there are legitimate concerns about quality, the use of occupational licensing to establish and maintain standards may eventually lead to “regulatory capture” — the control of a regulatory body by the industry they seek to regulate. For example, since a requirement to serve on an occupational regulatory board is expertise in that field, people already in a profession are in a position to decide who else to let in.

Who Needs a License? Becoming licensed can cost thousands of dollars and consume hundreds of hours, ultimately raising the price of goods and services.

African Hair Braiders. In 2006 Pennsylvania passed a law requiring African hair braiders to obtain a cosmetology license. Now braiders must complete at least 300 hours of training, or have three years of experience and complete 150 hours of training. Some say the law targets African art and will have a disproportionate effect on immigrants. Many immigrants do not speak English, thus completing classes would prove especially difficult. As of 2008, 16 other states and the District of Columbia also had hair braiding license requirements, according to the Institute for Justice.

Eyebrow Threaders. Eyebrow threaders — who use an ancient Eastern technique to remove unwanted hair using a twisted cotton thread — have run into similar difficulty. In Texas, for example, threaders must become licensed cosmetologists. The cost is considerable, though the requirements are largely irrelevant:

- Attending beauty school can cost $7,000 to $22,000, depending on the type of license sought, and most beauty schools do not teach threading.

- After beauty school, individuals must take a written and practical exam that costs $128; the exam does not test eyebrow threading.

- Those who pass the test must pay $53 annually to maintain their license.

This regulation is especially harmful to South Asian and Middle Eastern immigrants. Eyebrow threading is common in their home countries, and it is an easy source of income for them in the United States.

Health Care Professionals. State licensing laws require midlevel health care clinicians, who are allowed to practice with less supervision, to graduate from an accredited program. Professional organizations control the accrediting process, thus current professionals can impose higher education requirements. This raises the cost of becoming a midlevel clinician. Because there are fewer medical professionals, consumers are worse off, particularly those in underserved areas. Indeed:

- All states require physical and occupational therapists to have a master’s degree.

- In 2009, 18 states required a doctoral degree or its equivalent for new applicants to practice audiology; California plans to implement this requirement in 2012.

- By 2015, the American Association of Colleges of Nursing wants to require a Doctor of Nursing Practice degree of all new advance practice nurses.

Economic Cost of Licensing. Many jobs could be performed by unlicensed individuals at a lower cost, without sacrificing safety or quality. Licensing decreases the rate of job growth by an average of 20 percent and costs the economy an estimated $34.8 billion to $41.7 billion per year, in 2000 dollars, reports the Reason Foundation.

Registration and voluntary certification by professional and vocational organizations could offer comparable quality and safety standards, without the costly barriers imposed by licensing.

Courtney O’Sullivan is an editor with the National Center for Policy Analysis.