There is a looming physician shortage. Nonphysician primary care providers, or nurse practitioners, could help fill the gap. Nurse practitioners, also called advanced practice nurses in some states, have more advanced training than licensed vocational nurses or registered nurses, often earning a doctorate in their field before entering the workforce. This gives them the ability to diagnose and treat ailments much like a primary care physician.

Unfortunately, nurse practitioners are severely limited in some states, including Texas, Florida and New York. Other states, such as Alaska, Oregon and Maine, have fewer restrictions and wider access to the services provided by these professionals.

Growing Physician Shortage. There are 778,000 practicing doctors in the United States. Just under half of them are primary care physicians. Even before health reform, the Association of American Medical Colleges estimated that an additional 45,000 primary care physicians would be needed by 2020 to keep up with demand. The health reform bill is projected to increase demand for primary care, but did not include any funds to significantly expand the supply. Thus, health reform will compound shortages of primary care physicians.

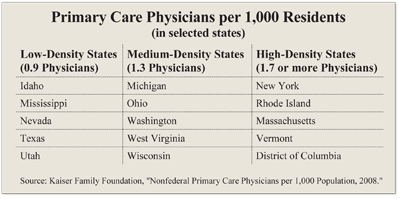

In fact, 21 percent of the U.S. population (66.9 million people) live in areas that are deemed to be Primary Care Health Professional Shortage Areas. The availability of primary care physicians varies significantly by region and among states: from 0.9 to 1.0 per 1,000 population in many Southern and Western states to between 1.4 and 2.8 per 1,000 in the Northeast. This means there are about twice as many doctors per 1,000 residents in the Northeast than in states such as Texas. [See the table.]

Case Study: Oregon versus Texas. Although scope of practice laws vary widely, the contrast of Oregon and Texas laws shows the problems associated with restrictive practice guidelines. Under Texas law, a nurse practitioner must be supervised by a doctor. Further:

- A physician cannot oversee more than four nurse practitioners at one time.

- The nurse practitioners must be located within 75 miles of the doctor’s office.

- The supervising doctor must randomly review 10 percent of the nurse practitioner’s patient charts each month.

In Oregon, by contrast, nurse practitioners with the proper credentials and license may open their practice anywhere they choose and provide the same services as a primary care physician without oversight from any other medical professionals. JoEllen Wynne is a good example. When she lived in Oregon, she owned her own practice. As a nurse practitioner, she could draw blood, prescribe medication (including narcotics) and even admit patients to the hospital. Wynne provided services similar to those of a primary care physician, without a doctor’s supervision. When she moved from Oregon to Texas in 2006, Wynne says, “I would have loved to open a practice here, but due to the restrictions, it is difficult to even volunteer.”

In Oregon, by contrast, nurse practitioners with the proper credentials and license may open their practice anywhere they choose and provide the same services as a primary care physician without oversight from any other medical professionals. JoEllen Wynne is a good example. When she lived in Oregon, she owned her own practice. As a nurse practitioner, she could draw blood, prescribe medication (including narcotics) and even admit patients to the hospital. Wynne provided services similar to those of a primary care physician, without a doctor’s supervision. When she moved from Oregon to Texas in 2006, Wynne says, “I would have loved to open a practice here, but due to the restrictions, it is difficult to even volunteer.”

Texas does little to help its 8,600 nurse practitioners open their own primary care clinics. The restrictions make it virtually impossible for nurses to practice outside the office of a primary care physician. In fact, the regulations discourage physicians from including supervision of nurse practitioners in their own practices. For instance, the Texas requirement that a doctor supervising nurse practitioners be physically present and spend at least 20 percent of her time overseeing them creates an incentive for the physician to require nurse practitioners in her office to be employees, rather than maintain their status as self-employed professionals. When practitioners are employed by a doctor, the physician meets state supervision requirements simply by showing up. This allows the doctor to see her own patients while generating additional revenue from patients seen by the practitioners.

These regulations have the greatest impact on the poor, especially the rural poor. Because the area served by the nurse practitioner is geographically circumscribed, it is often difficult for them to see rural residents. Furthermore, the farther a nurse is located from a doctor’s office, the less likely the physician will be willing to make the drive to supervise the nurse. This means that people living in poverty-stricken Texas counties must drive long distances, miss work and take their kids out of school in order to get simple prescriptions and uncomplicated diagnoses.

This problem might be alleviated if nurse practitioners were allowed to practice independently in rural areas. But, under Texas law, these practices must be located within 75 miles of a supervising physician. A physician with four nurses located in rural areas could drive hundreds of miles a week to review the nurses’ patient charts. The result is that doctors in Texas don’t receive a return on investment sufficient to induce them to supervise nurse practitioners.

Many physicians are concerned that the quality of care patients receive will suffer if patients are treated by less qualified personnel. The rationale for the restrictions in Texas is patient safety. However, when appropriate, some patients may prefer having the choice to receive treatment for minor conditions in a more convenient setting, such as a retail clinic with evening hours, even if it is by someone other than a traditional medical doctor.

Conclusion. The country cannot continue to discriminate against highly-qualified clinicians simply because they are not classified as primary care physicians. The solution is to reexamine scope of practice legislation and determine whether or not requiring a nurse practitioner to get a doctor’s permission before prescribing cold medicine is really a good idea.

Virginia Traweek is a graduate student fellow and John C. Goodman is President and CEO and Kellye Wright Fellow at the National Center for Policy Analysis.