With more children spending time in nonparental care, concerns about the quality of out-of-home care have increased. These concerns have led state and local governments to regulate and license facilities and caregivers. However, these barriers to entry make it more costly to become a child care provider, driving up the price of nonparental care.

Moreover, because parents respond strongly to increases in the cost of care, child care providers have not been able to raise prices when regulatory burdens have increased. Thus, rising regulatory compliance costs have led to lower staff wages. Low wages result in high staff turnover and low levels of job commitment, which negatively affects the quality of child care.

Who’s Watching the Kids? Many parents depend on multiple child care arrangements, and some have no regular caregivers. Interestingly, the proportion of children who receive care in large institutions (day cares and preschools) and the proportion who receive care by relatives have both increased in recent years. For example, according to U.S. Census data:

- The portion of children under age five who were in a day care center or preschool rose from 30 percent in 1995 to about 35 percent in 2005.

- Care by relatives (other than a parent) rose from 42 percent to 46 percent.

By contrast, the portion of children in family day care — that is, child care for a small number of children in the home of an unrelated provider — fell from 20 percent to 14 percent.

Child Care Costs and the Decision to Work. Over the past two decades, the federal government has provided more subsidies for institutional child care and has encouraged more stringent state regulation of child care. In addition, the states have put in place licensing requirements with the intention of improving the quality of out-of-home care. However, by making it more costly to become a child care provider, regulations and licensing requirements have driven up the price of nonparental care.

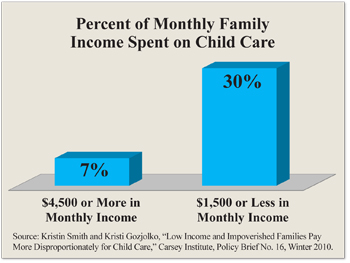

With rising prices, families have to spend ever-larger shares of their income on child care. Though low- and high-income families might spend the same absolute amount on child care, these expenditures as a percentage of income are much higher for poor families. Consider [see the figure]:

- Families with $4,500 or more in monthly family income spend only 7 percent of their income on child care.

- Families with less than $1,500 in monthly family income spend on average 30 percent of their income on child care.

The cost of child care is often so high that it becomes the deciding factor in a family’s decision whether to rely on welfare or seek employment.

Regulation and Quality. Public policies regarding child care generally have one or two goals: 1) raising the quality of child care to improve outcomes for the children, and/or 2) increasing the availability and affordability of child care to enable parents to pursue careers or education. The first goal is mostly pursued on the state level through regulation, such as group size limits, zoning laws and licensing requirements. The second goal is pursued through various federal child care subsidy programs. Unfortunately, state and local regulations significantly affect the price of care without improving quality, and federally subsidized programs are often plagued with long wait lists.

Regulation and Quality. Public policies regarding child care generally have one or two goals: 1) raising the quality of child care to improve outcomes for the children, and/or 2) increasing the availability and affordability of child care to enable parents to pursue careers or education. The first goal is mostly pursued on the state level through regulation, such as group size limits, zoning laws and licensing requirements. The second goal is pursued through various federal child care subsidy programs. Unfortunately, state and local regulations significantly affect the price of care without improving quality, and federally subsidized programs are often plagued with long wait lists.

Regulatory relief should not come at the expense of the quality of child care; it is therefore important to take a critical look at existing regulations and their effects on price and quality.

Group Size Limits. Studies have shown that maximum group sizes and maximum child-staff ratios do not significantly contribute to high quality child care outcomes. Instead, good child care outcomes are more closely connected to the quality of the interactions between the caregiver and the child. In addition, existing child care regulations have the unintended consequence of reducing staff wages at child care centers, while not having a significant effect on any measure of quality.

Licensing. Regulations that require child care workers to have credentials equivalent to a teacher do not improve care, but raise costs and create artificial shortages in service. Indeed, research indicates that the only educational measure that consistently matters for quality care is that the caregiver has taken a college course in early childhood education in the past year.

Zoning. In many places, zoning laws prohibit small family day care homes from operating in residential neighborhoods where affordable child care services are in particularly high demand. Intended to maintain the quality of life in a community, zoning laws prohibit business activities within residential neighborhoods and require high fees for permits that grant exceptions. However, if small family day care homes provide services mainly for the nearby residential community, concerns such as additional traffic and noise would be minimal compared to what already exists in a neighborhood of young families with children.

Conclusion. Instead of improving quality and making child care available to more families, regulation has led to higher prices for families and lower wages for child care staff without improving child care quality. Relaxing restrictions on group size and licensing and zoning requirements could significantly lower the cost of child care without lowering quality.

Diana W. Thomas is an assistant professor of economics in the Department of Economics and Finance at the Jon M. Huntsman School of Business at Utah State University.

This brief analysis is adapted from the NCPA task force report, Enterprise Programs: Freeing Entrepreneurs to Provide Essential Services to the Poor, which was funded by the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the Grantee, the National Center for Policy Analysis.