The federal and state governments levy taxes on gasoline and diesel fuel primarily to fund highway construction and repair. These taxes average nearly 49 cents on every gallon of gas purchased. However, a significant portion of revenue is diverted to other purposes, such as education and public safety.

In addition, states dedicate some of their revenues to nonroad projects mandated by the federal government.

Federal Fuel Taxes. A one cent per gallon federal gasoline tax was first enacted in 1932. By the time the Highway Trust Fund was established in 1956, the federal gas tax was three cents per gallon. Today, it is 18.4 cents. Sixty percent of federal gas tax revenue goes to highways and bridges, and the remainder is earmarked for specific programs, such as repairing lighthouses, paving bike paths and building museums.

The Federal Highway Administration (FHA) uses a complex series of calculations to allocate funds to the states to build and repair highways, including the interstate highway system, and for other transportation projects. Motorists in half of the states, including Texas, pay more taxes into the fund than their state receives back in federal apportionments. According to the FHA, Texas’ ratio of allocations to taxes paid was lower than any other state in 2009. Indeed, U.S. Department of Transportation data show that for every dollar Texans pay in federal fuel taxes, they received only 83.5 cents back. Texas has 3,233 miles of interstate highways — more than any other state — and is second only to California in cumulative payments into the fund, yet Texas “donates” funds to other states with far fewer people or miles of roads.

Federally Mandated Enhancement Projects. In order to receive federal highway funds, the states must comply with myriad federal mandates. For example:

- The Davis-Bacon Act requires most federally funded highway construction projects to pay workers union wages and benefits, which are usually higher than market wages and benefits.

- Some funds may only be used in areas that do not meet Environmental Protection Agency air quality standards, on projects intended to reduce emissions, such as carpool lanes or roundabouts to improve traffic flow.

About 10 percent of federal highway funds in the Surface Transportation Program must be used for traffic enhancements, such as highway beautification and transportation museums. Between 2005 and 2009, the program averaged $6.51 billion in revenue. This is a sizable portion of the roughly $32 billion a year in revenues collected by the Highway Trust Fund.

The Federal Highway Administration also allocates gas tax revenues to programs that are tangentially related to transportation, but do not involve building and maintaining roads and bridges. Indeed:

- From 1992-2010, $4.89 billion went to pedestrian and bicycle facilities, according to the National Transportation Enhancements Clearinghouse.

- Another $1.26 billion was used for landscaping and scenic beautification.

In addition, mass transit projects are allocated 2.86 cents of the 18.4 cent federal fuel tax, a diversion of about 16 percent of the tax from highway users.

Congress recently passed a bill extending federal highway and surface transportation programs for a few months. This act includes funding for transportation enhancements that, in the past, have included many projects that have nothing to do with maintaining highways and bridges. Consider:

- Ten years ago, a $140,000 federal grant was used to build a scenic park in downtown Asheville, North Carolina.

- In 2010, $198,000 went to a driving simulator installed in the National Corvette Museum.

Also in 2010, transportation enhancement funds were used to build amphibian crossings in Vermont, and $3.4 million was used to build a turtle crossing in Florida.

Also in 2010, transportation enhancement funds were used to build amphibian crossings in Vermont, and $3.4 million was used to build a turtle crossing in Florida.

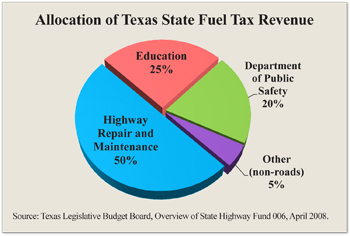

State Fuel Taxes. On average, American motorists pay 30 cents per gallon in state gasoline taxes. Like federal taxes, these are used for some nontransportation projects. For example, the Texas Constitution requires 25 percent of its state gas tax revenue to be spent on public education. The amount going to other nontransportation items varies from 20 percent to 25 percent, with $600 million to $750 million put toward nontransportation items in 2009. [See the figure.]

For a consumer who spends $3,000 per year on gas in Texas at an average gas price of $3.47 (including taxes):

- About $167 is spent on the Texas state gas tax.

- About $41 goes to public education.

- Another $40 to $44 per year is spent on other projects, with most of that going to the state’s Department of Public Safety.

This means that only half of the state’s fuel taxes are used for highway construction and maintenance.

In contrast, 30 states require that fuel tax revenues be used for highway transportation only, which excludes mass transportation projects, bike paths and any expenditures completely unrelated to highways.

Diverted Funds Displace Other Funding. Legislators claim their state must divert state highway funds due to budget shortfalls and insufficient general revenue. However, funds diverted to a popular cause, such as education, may displace rather than supplement other funding. This is apparently what has occurred with other revenue sources dedicated to education funding, such as state lottery revenue. According to a study by the National Gambling Commission, using state lottery revenue to fund education has resulted in declining funding for education in some states. Additionally, while lotteries initially bring in revenue for education, a study in Money magazine reports they reduce voters’ support for school bonds and tax increases to fund education.

Conclusion. In some states, constitutional changes would have to be made to dedicate fuel tax revenues only to highways and bridges. Meanwhile, the federal government should allow states to use federal funds for needed infrastructure repairs without mandating construction unrelated to roads.

Brian Bodine is a graduate student fellow and Pamela Villarreal is a senior fellow at the National Center for Policy Analysis.