Low-income families need transportation. They need to get to and from jobs, medical clinics and schools — in addition to markets for other jobs and services. The automobile is the most convenient form of transportation, but it is expensive to own and operate. Fares for public transit, such as buses, are low, but the service is slow and inflexible — and the buses may not go where the traveler needs to go.

In an ordinary market entrepreneurs would solve this problem by creatively meeting people’s needs. However, transit is so regulated that even the simplest solutions are often outlawed. For example, the demand for flexible, low-cost transportation could be met by enterprising drivers with vans. However, most cities do not allow individuals to pick up people and take them to job sites or medical appointments for whatever price the market will bear. Individuals are not allowed to compete with government buses or the limited number of approved taxi companies.

In an ordinary market entrepreneurs would solve this problem by creatively meeting people’s needs. However, transit is so regulated that even the simplest solutions are often outlawed. For example, the demand for flexible, low-cost transportation could be met by enterprising drivers with vans. However, most cities do not allow individuals to pick up people and take them to job sites or medical appointments for whatever price the market will bear. Individuals are not allowed to compete with government buses or the limited number of approved taxi companies.

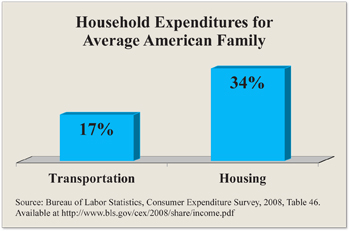

Transportation Demand Among the Poor. Transportation costs account for about 17 percent of the total household expenditures of the average American family, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics — second only to housing costs. [See the figure.] Thus, policies that affect transportation options have a significant impact on the general welfare of Americans.

Automobile use is high among every income group. Surprisingly, even those who do not own cars still make many of their trips by car. Indeed:

- Some 69 percent of individuals with incomes less than $20,000 per year own at least one vehicle, and 76 percent of all trips by low-income individuals are by automobile, according to the 2001 National Household Travel Survey.

- Even in households that do not own a vehicle, more than 34 percent of all trips are taken in a vehicle other than a bus.

- In fact, low-income individuals use taxis more frequently than the middle class.

How Jitney Services Were Outlawed. Competitive private bus or van services are called jitneys — vehicles with flexible schedules and stops (like a taxi) that offer a ride along a route that is fixed (like a bus), but from which the driver can detour, if passengers are willing to pay more. In the early 20th century, such services were widespread in urban areas. However, they competed with trolley lines and bus monopolies, and most jitney services disappeared by the 1920s.

Most city ordinances do not even mention the jitney, but they do not allow individuals to offer any transportation service unless they have the city’s permission to operate. However, the licensed services they do allow, such as taxis and chauffeured limousines (liveries), are also prohibited from offering jitney service:

Regulations Prevent Taxis from Offering Jitney Services. In most U.S. cities, the limit on the number of taxis ensures that they do not provide jitney services, rather than more profitable taxi service dispatched by a limited number of cab companies. Other regulations restrict vehicle size, group riding or shared rides. Furthermore, many cities explicitly bar competition between taxis and buses by prohibiting taxis from soliciting passengers at bus stops.

Regulations Prevent Commuter Vans from Offering Jitney Services. Licensed livery vehicles including limos, commuter vans and shuttles are strictly regulated like taxis. The most effective restrictions are on cruising and street hails. Some cities say that any ride on a commuter van must be prearranged by appointment, effectively limiting the convenience of a jitney service. Commuter vans are also strictly limited in size — usually between 7 and 15 passengers — to ensure that they do not compete with either taxis or buses if they do manage to offer jitney-type services.

Where Jitney Services Are Allowed. There are at least six cities in the United States that have some form of licensed jitney service. However, these services are regulated to the point that their value as a jitney service is severely limited. For example, Atlantic City licenses 190 jitneys to run on five routes. However, jitney operators are required to register with the Atlantic City Jitney Association and are restricted to five routes from which they cannot deviate. In addition, the routes are kept separate from bus routes, and jitney size is regulated to precisely 13 passengers.

In effect, the jitney service in Atlantic City is simply a bus route served by a private carrier. Rigid licensing and route restrictions prohibit jitneys from competing with other buses or with each other.

How Jitneys Could Become Widespread. Three distinct reforms are necessary to permit jitney operators to provide services valuable to low-income consumers:

- Eliminate prohibitions on group riding — particularly restrictions that prohibit taxis from picking up passengers when a passenger is already in the car, or those that require a full-trip fare structure.

- Eliminate regulations that prohibit commuter vans from picking up passengers without an appointment and from accepting street hails.

- Eliminate restrictions either on the number of jitneys per route or the number of jitney routes or the ability to deviate from a route.

If regulations in these three areas were repealed, jitney markets would be able to operate legally and would significantly improve the welfare of America’s poor.

Jennifer Dirmeyer is an assistant professor of economics at Hampden-Sydney College.

This brief analysis is adapted from the NCPA task force report, Enterprise Programs: Freeing Entrepreneurs to Provide Essential Services to the Poor, which was funded by the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the Grantee, the National Center for Policy Analysis.