Protection against criminality is a traditional function of government. Where government fails, however, people often turn to the private sector. That is why there are three times as many private security guards as public police. The need for private security is greatest for low-income families, since they are victimized by crime more often than other income groups. In fact, the rate of crimes against households in poverty is three times greater than against higher income families, according to U.S. Department of Justice data.

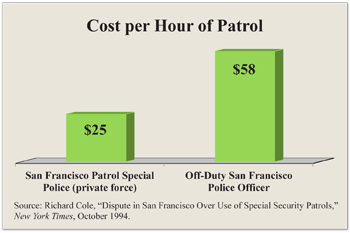

All too often, regulations price low-income families out of the market for private protection, however. Some cities only allow off-duty government police officers to patrol for private security firms, for example. Since hiring police officers costs two to four times as much as non-police private security guards, this type of regulation makes private security prohibitively expensive.

What Is Private Security? At the most basic level locks, alarms and armed self-defense are important forms of private security. Private security also includes informal volunteer policing and professional armed private police. Competition ensures that firms satisfy their customers in order to stay in business. Competing firms will not cut costs in ways that customers find unattractive. Any firm that offers unsatisfactory service will lose business and eventually be driven out of the market.

What Is Private Security? At the most basic level locks, alarms and armed self-defense are important forms of private security. Private security also includes informal volunteer policing and professional armed private police. Competition ensures that firms satisfy their customers in order to stay in business. Competing firms will not cut costs in ways that customers find unattractive. Any firm that offers unsatisfactory service will lose business and eventually be driven out of the market.

In many major cities today, housing complexes, neighborhood associations, airports, university campuses and shopping areas rely on various forms of private policing. Private security guards actually outnumber public police officers by a ratio of three to one, with 1.5 million employees in the private security industry. There are more than 9,000 private security firms in the United States alone.

Private Policing Reduces Crime. Economists Bruce Benson and Brent Mast have found evidence that private police reduce murder, robbery and auto theft, and strong evidence that private policing reduces rape. At the neighborhood level, private policing has significantly reduced crime rates in affected areas. Consider:

- After the “Grand Central Partnership,” an organization of over 6,000 businesses, hired a private security force to guard a 70-block area in the midtown Manhattan area, crime rates dropped by 20 percent after two years, by 36 percent after three years and 53 percent after five years.

- The introduction of private policing by Critical Intervention Services in a low-income area of Florida reduced crime an average of 50 percent.

Private Police Cost Less than Government Police. Private security agencies tend to provide services at lower prices than off-duty public officers, enabling poorer communities to buy their own security force. For example:

- In 1994 the San Francisco Patrol Special Police, a collection of independent private police, charged $25 to $30 per hour depending on the particular service, while off-duty public officers charged up to $58 for an hour of security service. [See the figure.]

- In Walnut Creek, California, local authorities estimated that it would cost taxpayers four times as much as a private security force to provide increased patrols and respond to calls in a private development.

- In order to save on the $1.8 million annual cost of sending police to respond to residential burglar alarms — 99.7 percent of which are false alarms — the chief of police in Arlington, Texas, proposed contracting with private security firms for alarm-response.

Regulatory Barriers to Private Security. Despite the benefits of private policing agencies, some high-crime neighborhoods do not hire them. Among the likely reasons are the cost of regulation and conflicts of interest among regulators.

High regulatory standards might improve the quality of private security, but increase the costs of compliance for security providers, thus reducing market competition and raising prices. Moreover, some regulations have dubious public safety rationale. For example, San Francisco regulates the color of the private Patrol Special Police officers’ uniforms and requires them to give the police access to proprietary information they can use to their competitive advantage, such as information about private contracts.

Additionally, regulators might block access to private alternatives because of their personal and/or institutional interest in the security market. Indeed, off-duty work is a lucrative opportunity for San Francisco police officers. Data from 2008 indicates that approximately 50 percent of the 2,300 strong police department work off-duty, earning an extra $9.5 million.

Conclusion. Private policing is an important policy option that should be considered by communities across the country. Although many policymakers believe that private officers might abuse their power because they are not as accountable as the public police, a 2006 report from the Colorado Department of Regulatory Agencies found no evidence that private security guards abuse their power, even in the absence of statewide regulation. Indeed, there are many examples where private policing works quite well, suggesting that people who are neglected or mistreated by government police will be better off if they, their landlords or local businesses are able to purchase more private security.

Kai Jaeger is a graduate student at Duke University and Edward P. Stringham is the Lloyd V. Hackley Endowed Chair for Capitalism and Free Enterprise Studies at Fayetteville State University.

This brief analysis is adapted from the NCPA task force report, Enterprise Programs: Freeing Entrepreneurs to Provide Essential Services to the Poor, which was funded by the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the Grantee, the National Center for Policy Analysis.