Welfare reform that emphasizes putting welfare recipients to work is the most successful public policy initiative of this century. As recently as five years ago, almost no one believed that by mid-1997 several states could cut their welfare caseloads – the number of people on welfare – in half. Yet according to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), between January 1993 and July 1997:1

- Alabama reduced its welfare rolls by 48 percent.

- Indiana, Oklahoma, South Carolina and Tennessee reduced theirs by 49 percent.

- Mississippi's cases declined by 50 percent, Colorado's by 51 percent, Oregon's by 52 percent and Wisconsin's by 58 percent.

- Wyoming's cases dropped by an astounding 73 percent.

"In the 11 months since the welfare reform bill went into effect, caseloads are down by almost 2 billion"

While most of the early successful reform efforts came from a handful of state initiatives, the federal government also played a major role by passing the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA). This legislation, which ended the 61-year-old cash entitlement program known as Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), has forced even the most reluctant states to submit plans for welfare reform. The sweeping change has had an impact nationwide, and even states that are not aggressively pushing welfare-to-work are experiencing significant caseload declines.2 In the 11 months since the bill went into effect, total welfare caseloads are down by almost 2 million, leaving some 10.2 million people still on welfare.3

In addition, welfare reform is saving both the states and the federal government hundreds of millions of dollars, while it is giving millions of low-income Americans who formerly got government handouts a sense of accomplishment and self-worth. No other American public policy initiative has achieved comparable results.

The important question is whether this positive trend can be continued, or even sustained. Some states were reluctant to join the welfare-to-work movement and have little to show for their efforts.4 For example, from January 1993 to July 1997, HHS figures show:5

- While the nationwide average decline in welfare rolls was about 24 percent, the decline was only 9 percent in Connecticut, 4 percent in Alaska and 5 percent in California.

- Washington, D.C.'s rolls dropped by a mere 2 percent.

- Hawaii had a 36 percent increase.

"Some states have little to show for their efforts – and Hawaii had a 36 percent increase in its welfare rolls."

Can the differences between successful and unsuccessful states – or even the state moving backwards – be attributed to population, geographic or other demographic or economic differences? In a word, no. While those factors can cause some differences, they can hardly account for such wide variations in caseload declines.6 For example, Oregon – a welfare reform success story – is sandwiched between far less successful California and Washington. Both unsuccessful New Mexico and successful Wyoming have small, rural populations, including substantial native American cohorts.

The primary difference between successful and unsuccessful states is the policies adopted and the diligence with which they are implemented. In what follows, we analyze several states' policies and draw some conclusions.

[page]

Before federal welfare reform legislation was passed, 45 states and the District of Columbia had received federally approved welfare demonstration waivers.7 Some waivers were limited in scope to in-state pilot programs, while others were statewide. Thus most states and the Federal District were actively engaged in welfare reform, even if limited, long before Congress passed the national welfare bill. But not all have been equally aggressive or equally successful in implementing reforms. [See Table I.]

"The average decline in welfare rolls nationwide was about 24 percent."

Because of political and economic differences between the states, there is not and cannot be a single model for welfare reform. Success – and failure – have many faces. Even so, there are similarities among the successful states, just as there are among states whose caseloads remain high. What are the apparent ingredients for successful reform?

- First and foremost, a serious effort to move welfare recipients into jobs quickly, preferably private-sector jobs.

- A political commitment to reform that transcends one person or party.8

- A willingness to extend some health care, child care and other social service benefits for a period after the welfare beneficiary takes a job.

- A stress on personal, individual responsibility.

- An attempt to integrate social reform – such as making sure teen mothers attend school – with welfare reform.

- A reliance on private-sector services whenever possible.

States that have incorporated most or all of the elements listed above are enjoying success at reforming welfare. A closer look at the most successful states shows why.

"Even during the 1990-93 economic slowdown, Wisconsin's caseload remained level or declined slightly"

Welfare-to-Work Success: Wisconsin. Gov. Tommy Thompson has long promoted aggressive reform of the welfare system. He campaigned on a reform platform and rallied widespread support for his program. While many states have implemented welfare-to-work efforts only recently, Wisconsin committed to reform a decade ago, and the state's subsequent success has strengthened its political commitment.

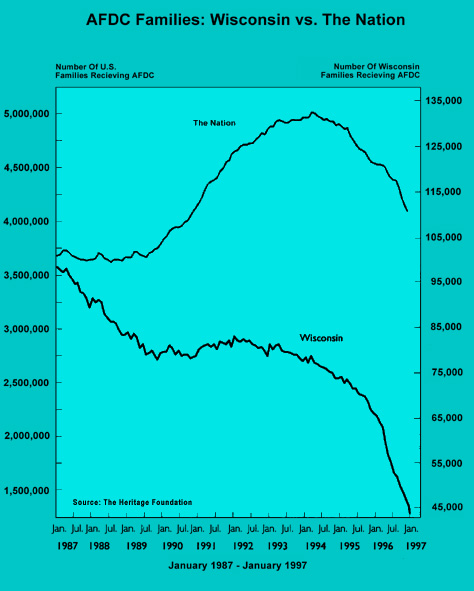

- From January 1987 to January 1997, Wisconsin reduced its welfare caseload by 53,147, a net reduction of 54.1 percent – compared to a 9.6 percent increase in the caseload nationally over the same period.9

- In 1987 the state sent out welfare checks totaling $46 million each month; this year the figure is $21 million a month, a saving of some $300 million in 1997 alone.10

- Since September 1997, with the implementation of the Wisconsin Works (W-2) program, welfare caseloads have decreased by one-third and state officials estimate that by March 1998 the remaining two-thirds of welfare recipients will be working – every one of them will be doing something in return for a check.

Wisconsin's experience answers one of the most frequent criticisms of current welfare reform: that declining caseloads can occur only in a good economy. As Figure I shows, even during the economic slowdown of 1990 to 1993, when welfare rolls for the nation as a whole rose dramatically, Wisconsin's caseload remained level or declined slightly.

"Welfare reform in Wisconsin began with one simple premise," according to Thompson. "Every person is capable of doing something."11 This philosophy was implemented in several phases, beginning with the Work First program, and expanded in 1995 by adopting the more comprehensive welfare reform legislation known as Wisconsin Works. In this legislation the state adopted a four-part plan for moving welfare recipients to work:

- Those who are job-ready immediately are placed in an appropriate, unsubsidized job, usually in the private sector.

- Those without a work history are placed in a subsidized job for a limited time – usually six to nine months.

- Those with few skills and poor work habits are placed in community service jobs for six to nine months to learn needed skills and work habits before being placed in the private sector.

- Those incapable of even community service work are placed in the state's W-2 Transitions program and required to participate in activities consistent with their abilities.

To centralize its efforts, Wisconsin established Job Centers that provide one-stop employment and job training.

"Wisconsin complements its welfare-to-work program with several other reforms."

Wisconsin complements its welfare-to-work program with several other reforms. For example, Learn Fare requires families to keep their school-age children in classes in order to receive a welfare check. Children First has increased child support payments significantly by giving fathers a choice: either pay child support or go to jail. Further:

- In January 1994, the state passed legislation deemphasizing the role of additional education, which is costly and often has little impact on getting people back to work.

- In December 1995, Wisconsin passed legislation that created incentives for state bureaucrats to help recipients leave the welfare rolls – or stay off them in the first place.

- In March 1996, Wisconsin began diverting potential welfare recipients into Pay for Performance, a program in which applicants first meet with financial and employment specialists who identify the alternatives to welfare, the services available to help them find employment and child care options.

As a result of Wisconsin's strong commitment to work for anyone receiving a welfare check and its willingness to try new and innovative programs, it has demonstrated that welfare reform can work, even in slower economic times.

Welfare-to-Work Success: Oregon. Welfare reforms being implemented in Oregon, Mississippi and six other states are based on the premise that most welfare recipients can go to work immediately and that most training should take place on the job. The vision underlying the Full Employment Program is that able-bodied welfare recipients should get a paycheck, not a welfare check. While this program varies slightly from state to state, in Oregon it includes:

- Subsidized jobs at the minimum wage or higher. Federal and state money that was used to fund food stamps and AFDC is used instead to subsidize mainly private-sector jobs. Employers must pay participating workers at least the minimum wage and as much as they pay like-trained employees. The program guarantees that participants receive more spendable income (when the Earned Income Tax Credit is included) than they would get from a welfare check. The average pay is more than $6.45 an hour.

- Incentives for employers. The program subsidizes employers in an amount equal to the minimum wage plus FICA taxes, unemployment insurance and workers' compensation insurance premiums.

- Opportunities for advancement. If the employer has not offered the participant an unsubsidized job after four months, the participant is paid for eight hours of job-search time every week for the next two months. If the participant does not find an unsubsidized job, at the end of the period he or she may switch to another subsidized job with another employer.

- Temporary continuation of noncash benefits. Those who would normally qualify for Medicaid retain their eligibility and receive child care if they need it.

- Educational opportunities. Participants in a subsidized job may receive guidance and counseling, including life skills classes. They may also enroll in classes to earn a General Education Development (GED) diploma. However, they learn job skills primarily on the job, not in a classroom.

"Four out of five people who took subsidized jobs moved on to unsubsidized jobs during the first 14 months of the pilot project."

Oregon was the first state to adopt a Full Employment Program (JOBS Plus) in a three-year, six-county pilot project. At the same time, the state implemented a jobs-oriented philosophy in other counties. Many welfare recipients quickly found unsubsidized jobs when faced with the reality of losing their benefits. Others left the system, presumably because they had better alternatives.12

- Of the approximately 2,200 people taking jobs in the six pilot counties, about 80 percent did not need the government subsidy, saving the system millions of dollars in welfare spending. [See Figure II.]

- Of those who did take subsidized jobs, four out of five moved on to unsubsidized jobs during the first 14 months.

A more detailed examination of results in one of the pilot counties demonstrates one reason why welfare-to-work saves money: faced with having to take a job, about a third of the people simply leave the system. In Beaverton, 549 people applied for welfare between February and July of 1996.13 Of that number:

"Many Welfare recipients quickly found unsubsidized jobs when faced with the reality of losing their benefits."

- About 35 percent signed up for JOBS Plus but found an unsubsidized job within the first 30 days.

- About 33 percent left the program voluntarily or refused to cooperate and are in the process of losing their welfare benefits.

- Eight people out of 549 actually required a subsidized job.

Because of the work requirements, more welfare recipients are leaving the system, fewer are signing up for benefits and the state is saving money.14

- Within three months of the JOBS Plus program's limited 1994 introduction, the number of families on welfare began falling. The numbers are down about 53.2 percent since the beginning of 1994, from 42,000 to 20,606, including a caseload drop of 8,000 in just the last 12 months.

- 95 percent of two-parent families and 75 percent of single-parent families are taking part in work activities.

Welfare-to-Work Success: Virginia. Taking a more comprehensive approach under Gov. George Allen, Virginia passed legislation that went into effect in July 1995, intended to move welfare recipients to work while addressing some of the social problems that trap people in the welfare system. The work-related provision of the legislation, known as the Virginia Initiative for Employment Not Welfare (VIEW), requires able-bodied AFDC recipients to begin some type of work activity within 90 days of entering the welfare system. If recipients fail to find work, then caseworkers can place them in community work to gain experience.

At the same time, the state adopted the Virginia Independence Program (VIP) to counter social problems that make it difficult for some families to leave the welfare system. For example:

- Mothers must name the father(s) of their children. As of July 1996 – when an assessment was made of the first year's progress – the state had experienced a 99.6 percent compliance rate with this provision. [See Figure III.]

- Most children, including minor mothers, must attend school to receive their benefits. By the end of the first year, 99.5 percent of the AFDC children had complied with the mandatory school provision.

- Unlike traditional welfare, which penalized welfare families frugal enough to save some money, the state permits low-income families to save up to $5,000 for purposes of education, home ownership or to start a business.

- The state imposes a "family cap," providing no additional cash benefits when a family already receiving benefits has another child.

What has been the state's year-long overall experience with these reforms?

- More than 30 percent of Virginia's total welfare caseload went to work in order to avoid a loss of benefits.

- The welfare caseload declined 14 percent after only the first year, saving Virginia taxpayers $13.8 million.

"Success in neighboring Fairfax County presents a contrast with Washington D.C."

However, Virginia's experience provides additional insight into those districts that have not made a strong commitment to a welfare-to-work initiative, such as neighboring Washington, D.C., whose welfare caseload has dropped only 2 percent.

Fairfax County in Virginia borders on Washington, D.C., yet according to data from the county:15

- 1,880 individuals enrolled in the VIEW program between April 1996 and April 1997.

- 1,226 of these participants found employment, with 1,051 finding full-time jobs.

- The average rate of employment retention was 71 percent.

"In Virginia, 99.6 percent of mothers named the father(s) of their children, and 99.5 percent of children attended school."

Because Virginia's welfare reform legislation provided some local flexibility, not all of the state's counties responded with a strong work program. Neighboring Arlington County did not put as much initial emphasis on work as Fairfax did and quickly discovered it would not meet the state's goals. Arlington officials had to quickly revise their county's plan.16

Welfare-to-Work Success: Michigan. In October 1992, Michigan's Gov. John Engler obtained a federal waiver for the implementation of the To Strengthen Michigan Families (TSMF) program. The program encourages parents to stay together by eliminating "marriage penalties." Welfare mothers are permitted to keep the first $200 a month of their earnings without losing anything from their welfare checks. Transitional child care and medical coverage are provided when recipients reach the earnings limit and lose cash assistance.

Under Michigan's Work First program, welfare recipients must work at least 20 hours a week or actively seek a job within 60 days or lose benefits. Work First is a collaborative effort between Michigan's social services office and its job commission. It uses local boards, generally with a private-sector majority, to coordinate employment opportunities.

Most recently, Michigan implemented Project Zero in six areas of the state. A small research effort, Project Zero is identifying personal characteristics, demographic information, client strengths and barriers to employment of welfare recipients. Private-sector companies work with the project to help place recipients in jobs.

"Since Michigan launched its program, 129,016 welfare recipients have left the rolls because they were earning too much money to qualify."

Like other aggressive welfare reform states, Michigan has seen its caseload drop significantly. In 1991, Michigan's Family Independence Agency (formerly the Department of Social Services) had a welfare caseload of 245,000. Since the launch of the program in October 1992:

- 129,016 welfare recipients have left the rolls in Michigan because they were earning too much money to qualify.

- Cases without earned income decreased from 178,751 in September 1992 to 88,156 in September 1997.

Although Michigan has experienced only a 38 percent decline in welfare cases since January 1993 – much less than the decline in some other states – it demonstrates that even states with large urban centers and chronically underemployed inner-city populations can reduce their welfare rolls.

Other Welfare-to-Work Successes. Among the other states successful in reducing their welfare rolls is Mississippi, which adopted a version of the Full Employment Program pioneered by Oregon. Though the program was not implemented statewide, in less than five years:17

- The welfare caseload was down from more than 61,000 to 32,288 as of August 1997 – a decline of 47.1 percent.

- In the past year alone, the number of people receiving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) is down 29.8 percent.

- In August 1997, 143,617 households received food stamps, a 29 percent drop from 200,000 in 1993.

"Wyoming, with the least population, has the largest reduction in welfare cases – 73 percent."

Even though it began welfare reform only in December 1996, Wyoming (with the nation's smallest population) can boast a 73 percent reduction in welfare cases – the largest percentage decline in the country. Under Gov. Jim Geringer, Wyoming's Personal Options with Employment Opportunities (POWER) program encourages self-sufficiency through work. In contrast to Wisconsin's Pay for Performance, Wyoming's work program is called Pay after Performance to stress that a recipient must work for benefits.

As does Michigan, Wyoming requires that each client sign an Individual Responsibility Certificate of Understanding that defines performance requirements. The purpose is "to promote and support individual and family responsibility through the belief that parents, not government, should be responsible for themselves and their children."

Although Vermont can only claim a moderate reduction in welfare recipients, its 1994 welfare reform legislation is significantly reducing teen pregnancy. Prior to reform, Vermont provided cash assistance and helped young girls who had become pregnant get their own apartments. Now teens with children must live under supervision and cannot collect welfare if they set up an independent household.18

As a result of this and other restrictions, the number of teenage mothers in Vermont is down 25 percent, compared to a 12 percent decline nationally, with no detectable increase in abortions. [See Figure IV.]

[page]While the states discussed above are making welfare work, many states are not. And some are actually impeding reform. While failure to achieve significant caseload reductions is often a result of legislative inaction, there are a number of other obstacles that can limit or stop even serious welfare reform attempts. The following are some examples:

"The number of teenage mothers in Vermont is down 25 percent, compared to 12 percent nationally."

(1) Elected officials who refuse to pass strong welfare-to-work policies. Even though a few states are celebrating welfare roll reductions of 50 percent and more, many elected officials remain unconvinced that welfare-to-work policies are effective. They argue that caseloads are dropping due to the good economy or to states' simply dumping welfare recipients from the rolls.19 Further, some elected officials are reluctant to move welfare-to-work legislation for fear of being attacked as enemies of the poor. Welfare reform usually has a political cost that diminishes only after caseloads plunge and state savings soar.

Some elected officials also complain that too few jobs are available for all their welfare recipients. For example, a recent report released by the U.S. Conference of Mayors predicted a shortfall of 194,000 jobs in nine major cities between 1997 and 1998.20 Not surprisingly, the paper claimed more federal money would help solve the problem.

For these and other reasons, many elected officials remain uninterested in implementing federal welfare legislation or passing state legislation. They may comply with federal law – by November 1997 all states, Washington, D.C., and the territories had submitted approved HHS reform plans21 – but they are not interested in ensuring that the reforms work.

(2) State welfare bureaucracies that are unwilling to implement legislated welfare reforms. One of the biggest hindrances to effective welfare reform is the recalcitrance of government employees charged with implementing the reforms. Since they deal with welfare cases daily, they can impede any reform legislation. Wisconsin has helped solve this problem by providing incentives for them to decrease the caseload.

"Public employee unions fear that dramatic declines in welfare caseloads will lead to job losses by their members."

(3) Public employee and other labor unions that fight welfare-to-work legislation or try to burden employers who hire welfare workers. Public employee unions are concerned that dramatic declines in welfare caseloads will lead to job losses by their members. Of course, the fear of government downsizing is exaggerated. Even though caseloads are declining dramatically in some states, clients who remain on welfare often need significant help to become job-ready. For example, they may have substance abuse problems, physical abuse histories or learning impediments. Social workers with fewer clients are able to focus on those who need more assistance.22

In addition, labor unions have expressed concern that employers will substitute lower-paid welfare recipients for higher-paid union workers. The way to allay this concern is to ensure that employers do not replace union workers with welfare recipients. This is a fundamental principle of the Full Employment Program used in Oregon and six other states.

Unions can also undermine welfare reform by demanding that firms hiring welfare recipients abide by all existing labor rules, including the minimum wage law.23 In response to union concerns, Congress recently passed legislation that could hamper states' efforts to deal with some difficult welfare cases.24

(4) Failing to emphasize the need to go to work immediately. While federal reform legislation requires states to move welfare recipients into work, the legislation still permits recipients two years of benefits. About 20 states have passed legislation reducing the maximum time limit, with 11 of those requiring recipients to go to work immediately. However, others have made little attempt to tighten the time frame and are experiencing a slower decline as a result.

(5) Willingness to provide education and training without requiring work. Successful states know that the best training occurs on the job. Yet the federal government and many states provide expensive, time-consuming training programs or pay college tuition for courses that seldom lead to a job.

The worst example is the federal Job Opportunities and Basic Skills Training (JOBS) program. This program, created in 1988, requires states to provide education, training and support services for welfare recipients. Because the goals of the legislation are broadly defined, states have some flexibility in meeting the specific needs of their residents. But a recent report by the General Accounting Office (GAO) shows the JOBS program is a failure. According to the GAO, about $8 billion was spent on JOBS between 1989 and 1994, but "HHS does not know whether JOBS is reducing welfare dependency because it does not gather enough information on critical program outcomes, such as the number of participants entering employment and leaving AFDC annually."25

In an effort to assess of the cost-benefit ratio of JOBS, the GAO visited five locations reputed to place a strong emphasis on job placement. The agency found that:

- At one location, training programs cost $6,000 to $7,000 per person over a six-month period, and another program cost $6,600 per participant – with welfare benefits additional in each case.

- Nationwide, in mid-1994 about 10 percent of JOBS participants were placed in work-experience positions and about 1 percent were in subsidized jobs. The rest were never employed. [See Figure V, and compare it with Figure II.]

"Only 11 percent of JOBS participants found jobs."

Most JOBS participants apparently make the minimum effort necessary to stay in the program and continue collecting benefits. Thus they make little or no progress toward getting back into the workforce. State-based education programs exhibit the same pattern of failure.

(6) Paying extremely high benefits. People on welfare often face a choice between taking a low-paying job with few or no benefits and collecting welfare. The higher the welfare compensation package (i.e., cash plus benefits such as Medicaid, housing subsidies, etc.), the harder it is for social workers and employers to move recipients from welfare to work. As Figure VI shows, many states offer welfare compensation packages two to three times higher than the minimum wage. While no one advocates reducing benefits to zero, providing excessively high benefits deters people from accepting perfectly decent jobs.

Each of the obstacles listed can undermine a state's welfare reform attempts – and often has. For example, Texas sought to privatize the delivery of welfare services, which would have cost a number of public employees their jobs. Unions strongly opposed this approach, and the Clinton administration vetoed the state's waiver request to privatize.

In addition, the federal government can be a hindrance. Federal bureaucrats who interpret PRWORA very narrowly have limited state flexibility, as have congressional revisions to the legislation. As a result of all of these obstacles, the future success of welfare reform is uncertain.

[page]

Like the states that have succeeded in reforming welfare, the states that have failed have much in common. Most have encountered one or more of the obstacles mentioned above. Unless they make concerted efforts to overcome the obstacles, the federal welfare-to-work requirement will have little impact.

"Hawaii's liberal welfare rules permit eligible persons to recieve benefits in the first day they enter a welfare office."

Welfare-to-Work Failure: Hawaii. Hawaii's 36 percent increase in welfare cases since 1993 is an anomaly. State representatives blame the economy, but Hawaii's 5.9 percent unemployment rate is only slightly above the national rate of 4.7 percent.

The real reason for Hawaii's growing caseload is that state officials remain largely unconvinced of the need for welfare reform. According to the state's welfare program administrator, "People say we're too generous, we're too nice. But a lot of people here feel welfare reform is too punitive. We do not want to mirror that."26

As a result:

- Hawaii's liberal welfare rules permit eligible persons to receive benefits the first day they enter a welfare office.27

- According to Michael Tanner of the Cato Institute, welfare recipients in Hawaii receive the largest welfare compensation package in the country, with an annual pretax wage equivalent of $36,650, or $17.62 per hour (1995).28

With Hawaii's inviting climate, generous welfare package and official willingness to make welfare easily available, is it any wonder that Hawaii's caseload is growing rapidly?

"Many states offer welfare compensation packages two to three times higher than the minimum wage."

Welfare-to-Work Failure: Alaska. One could not imagine a greater contrast between Hawaii and Alaska. Besides the climatic differences, Hawaii is a liberal state run by Democrats, while Alaska is conservative and controlled by Republicans – whose party has driven most successful states' welfare reforms. Yet Alaska has experienced only a 4 percent decline in caseload.

Part of the reason has to do with its indigenous population. There are some 200 villages inhabited primarily by Alaska's native population. Some of these villages are wealthy due to oil revenues. But many of them live at subsistence levels, continuing their traditional lifestyles of hunting and fishing.29 Some of these villages approach a 50 percent unemployment rate. However, since they enjoy their traditional ways, welfare-to-work reform is probably not appropriate.

Another factor is that welfare recipients in Alaska receive an annual compensation of $32,150, or $15.48 per hour, which is the second highest welfare compensation package in the country.30 [See Figure VI.] Even though both Hawaii and Alaska are high cost-of-living states, such high benefits make it very difficult for employers to compete.

Welfare-to-Work Failure: California. While California is home to 12 percent of the U.S. population, it has 19 percent of the nation's AFDC caseload and accounts for almost 30 percent of the nation's total AFDC expenditures.31 Over the same 10 years in which Wisconsin cut its welfare caseload by 54 percent, California posted an increase of 63 percent.

One reason for California's failure is the state's initial delay of welfare reform. California was able to implement a very limited welfare reform program, known as Greater Avenues for Independence (GAIN), prior to the passage of federal reform. However, critics contended the program was too limited and expensive. The state also had difficulty getting its federal waivers approved. As a result, it could not require work as a condition of receiving aid, impose time limits or provide financial work incentives for welfare recipients.32

Even so, the state might have implemented effective reform, as Gov. Pete Wilson hoped, when it responded to the federal welfare law. However, opponents watered down the legislation, and a state in dire need of reform is seeing little change.

Welfare-to-Work Failure: New York. New York faces a number of problems in attempting to implement welfare reform, especially in New York City, which has often been considered a welfare mecca. While New York City has been implementing welfare reform, its stress on workfare rather a program that would put welfare recipients in real jobs has limited its accomplishments.

"New York has 320,000 fewer people on its welfare rolls, but 200,000 of them are in the nation's largest workfare project, not in real, private-sector jobs."

Four years ago New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani took action to move New York City's then 1.1 million welfare recipients off the rolls. In part relying on four-week programs known as "job clubs" to help welfare recipients find jobs, the city now has some 320,000 fewer people on its welfare rolls.33 However 200,000 of these have been relegated to the nation's largest workfare project. Critics argue that until recently the city focused primarily on placing recipients in six-month workfare jobs with continued benefits rather than on helping them find real, private-sector jobs.34

The movement into workfare has also aroused unions that want to ensure that welfare recipients are receiving protections and benefits and are not replacing union workers.35

In addition, two of New York City's most important welfare components, housing and child services, have experienced very little reform. While Giuliani created a new Administration for Children's Services to help with the city's endangered children, a recent analysis determined that the program had severe organizational problems.

The mayor's position is that he has taken the city a major step in the right direction – a fair assessment considering how far New York City had to come and the obstacles it still has to conquer. But he also concedes the city has a long way to go to reach the success that other cities and states have achieved.36

"Washington D.C., actually has undermined efforts to get its welfare recipients off welfare and into jobs."

Welfare-to-Work Failure: Washington, D.C. While the neighboring Virginia counties of Arlington and Fairfax are aggressively implementing welfare reform, Washington, D.C., has actually undermined efforts to get its 70,000 welfare recipients – about 25,000 households – off welfare and into jobs. The District did create a task force in the fall of 1996 to make recommendations about how the city should comply with federal welfare reform requirements. And the task force made a number of recommendations similar to those of many of the successful states. However, Mayor Marion Barry was reluctant to act on those reforms. "We're going to do this in a way that does not harm or hurt those it is designed to help," the mayor said. "We cannot give up on those people, even if they have given up on themselves."

While the District did pass a reform plan in December that received HHS approval in March, the city has already fallen behind in implementing the plan. The District had designated the Department of Employment Services (DOES) to train those going to work, but then removed $7 million from the department's training budget to cover other expenses. However, considering DOES's failing track record, it is not clear that preserving the money would have made the program successful.

As a result of these negative efforts from elected officials and bureaucrats, the District has had little success moving people off welfare. In addition, when it appeared it would be out of compliance with federal targets, and would thus lose some of its federal welfare dollars, the city sought a federal waiver to exempt it from complying with the law – a law whose requirements many other states have easily surpassed.

[page]The states that have successfully reformed their welfare systems demonstrate once again that incentives work. When states adopt incentives that encourage people to take a job and help them make the transition so they can keep it, the welfare caseload drops dramatically.

"The Conference of Mayors sought more federal money to create make-work jobs – showing that this powerful group still misunderstands the principles of reform."

The states that have not successfully reformed point out the obstacles to making welfare reform work. Unfortunately, it is not clear at present whether welfare-to-work efforts will be successful nationwide. Thus a request from the U.S. Conference of Mayors for more federal money to create more jobs for welfare recipients shows how one powerful group still misunderstands the need to put welfare recipients into real jobs, preferably in the private sector. For example, the Full Employment Program adopted in Oregon and several other states uses a welfare recipient's cash allotment to subsidize a newly created private-sector job. That job can supply the welfare recipient with new hope, new skills and a new sense of dignity. The Conference of Mayors' approach, by contrast, would use public money to create public, make-work jobs with no future and no hope.

Such a proposal does not end welfare; it simply puts cities, rather than individuals, on the welfare dole.

Unless elected officials, government employees, unions and the public are serious about welfare reform, the movement will die slowly, with critics saying "we told you so" – even as they continue to undermine reform efforts.

The question is not whether states can make welfare reform work; many already have. The question is whether opponents will scuttle these and other efforts and sentence millions of Americans to the continuing cycle of poverty and despair.

NOTE: Nothing written here should be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of the National Center for Policy Analysis or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before Congress.

[page]- "Change in Welfare Caseloads, As of July 1997," Administration for Children and Families, Department of Health and Human Services.

- An important new study by Thomas L. Gais, Donald J. Boyd and Elizabeth L. Davis analyzes some of this spillover effect; "The Relationship of the Decline in Welfare Cases to the New Welfare Law: How Will We Know If It Is Working?" Nelson A. Rockefeller Institute of Government, State University of New York, Albany, N. Y., August 19, 1997.

- Christopher Georges, "U.S. Tightens Grip on States' Ability to Run Their Own Welfare Programs," Wall Street Journal, November 18, 1997; and James Bennet, "Clinton Urges Companies to Hire Off Welfare Rolls," New York Times, November 18, 1997.

- A September 1997 survey by the Associated Press found that only 17 states expected to meet the federal law's work requirement for two-parent families by the deadline. Jason DeParle, "Half the States Unlikely to Meet Goals on Welfare," New York Times, October 1, 1997.

- "Change in Welfare Caseloads, As of July 1997."

- For example, Gais et al. suggest that there is "general agreement that a 1 percent increase in the unemployment rate could lead to a caseload increase of between 2 – 5 percent." While that relationship is significant, it could not explain the wide variations experienced by several states.

- "Summary of Selected Elements of State Plans for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families as of August 12, 1997," NGA Center for Best Practices, National Governors Association.

- For example, Oregon's Administrator of Adult and Family Services, Sandie Hoback, credits "bipartisan support for the state's unique brand of welfare reform" as a primary reason for the state's success. Statement from the Oregon Department of Human Resources, August 7, 1997.

- Robert Rector, "Wisconsin's Welfare Miracle: How It Cut Its Caseload in Half," Policy Review, Heritage Foundation, Washington, D.C., March/April 1997.

- Tommy Thompson and William J. Bennett, "The Good News About Welfare Reform: Wisconsin's Success Story," Heritage Foundation, Heritage Lectures No. 593, Washington, D.C., March 6, 1997.

- Ibid.

- Merrill Matthews Jr., "Does Welfare Reform Cost More?" National Center for Policy Analysis, NCPA Brief Analysis No. 210, August 23, 1996.

- Statistics provided by the welfare office in Beaverton.

- Statistics from the American Institute for Full Employment. Each case represents a welfare family, not the total number of people on welfare.

- Clarence Carter, Denise Dumbar et al., "Virginia: Promoting Independence and Employment," Public Welfare, Summer 1997.

- Ibid.

- Statistics from the American Institute for Full Employment. Each case represents a welfare family, not the total number of people on welfare.

- Dana Milbank, "Vermont Credits Sharp Drop in Teenage Births to Tougher Welfare Rules, Crackdown on Dads," Wall Street Journal, November 24, 1997.

- While a strong economy can be helpful, it also can be a hindrance to real welfare reform. In a good economy states experience a certain decline in their caseloads even if they do nothing – which lets politicians take credit for the declining caseload without suffering the political pain of reform.

- Carol Jouzaitis, "Cities Say Jobs Lacking for Ex-Welfare Clients," USA Today, November 24, 1997.

- "Summary of Selected Elements of State Plans for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families as of November 6, 1997," NGA Center for Best Practices, National Governors Association.

- See, for example, Jason DeParle, "Newest Challenge for Welfare: Helping the Hard-Core Jobless," New York Times, November 20, 1997.

- See Christopher Georges, "GOP Drive to Deny Workfare Benefits Sputters in States," Wall Street Journal, October 7, 1997.

- On attempts to undermine welfare reform, see Robert Rector, "Washington's Assault on Welfare Reform," Heritage Foundation, Issue Bulletin No. 244, August 14, 1997.

- General Accounting Office, "Welfare to Work: Most AFDC Training Programs Not Emphasizing Job Placement," GAO/HEHS-95-113, Washington, D.C., May 1995; and General Accounting Office, "Welfare to Work: Measuring Outcomes for JOBS Participants," GAO/HEHS-95-86, Washington, D.C., April 1995.

- Rachael L. Swarns, "Hawaii Bucks the Trend on Welfare Reform," New York Times, September 28, 1997.

- Ibid.

- Michael Tanner, The End of Welfare: Fighting Poverty in the Civil Society (Washington D.C.: Cato Institute, 1996), Table 2.3, p. 66.

- All Alaskans also receive about $1,000 a year as part of the "permanent fund" dividend, providing some cash to low-income populations and making work less necessary.

- Tanner, The End of Welfare: Fighting Poverty in the Civil Society.

- John C. Liu, "The Overlooked Facts about Welfare in California," Pacific Research Institute, San Francisco, Calif., May, 1997.

- Ibid.

- Rachel L. Swarns, "Analysis: Giuliani's Grade on Welfare Reform – Incomplete," New York Times, October 29, 1997.

- Ibid.

- "Workfare in New York: The New Slavery?" Economist, October 5, 1996.

- See "Excerpts from Mayor's Conversation with Editors and Reporters," New York Times, November 1, 1997.