On May 30, 2005, the French people voted to reject the proposed European Union (EU) Constitution. Exit polls showed that the majority of those who voted against the Constitution did so because they believed it would result in an influx of "Polish plumbers"-cheap Eastern European workers lured westward by France's higher wages and better workplace benefits. With the defeat of the Constitution, leaders of the "no" campaign in France have joined forces with labor unions across Western Europe to oppose an EU Commission plan- the Services Directive-that is widely seen as an attempt to open a backdoor for Eastern workers into Western markets.

On May 30, 2005, the French people voted to reject the proposed European Union (EU) Constitution. Exit polls showed that the majority of those who voted against the Constitution did so because they believed it would result in an influx of "Polish plumbers"-cheap Eastern European workers lured westward by France's higher wages and better workplace benefits. With the defeat of the Constitution, leaders of the "no" campaign in France have joined forces with labor unions across Western Europe to oppose an EU Commission plan- the Services Directive-that is widely seen as an attempt to open a backdoor for Eastern workers into Western markets.

The proposed Services Directive would require EU governments to remove the regulatory barriers that prevent Eastern European service providers (like Polish plumbers) from operating in Western Europe. The Directive has been controversial:

- Proponents claim the Directive would benefit Eastern and Western Europe alike by fueling job growth, increasing wages and driving down prices.

- Critics claim the proposal-like the Constitution before it-would clear the way for an avalanche of Eastern workers who would compete for scarce jobs, drive down wages and place a strain on Western Europe's generous national welfare programs.

- Economists say the net effect of the Directive would be positive, but warn that wide-scale liberalization is not a frictionless process-in some sectors, efficiency gains will inevitably lead to job losses.

Despite the initial pain of adjustment, opening up the services sector is a step in the right direction for Europe's economy and a win-win proposition for both sides of the integration debate. In the current period of reflection following the rejection of the Constitution, liberalization would build confidence in the EU's ability to complete the Single Market-a region-wide free trade area and customs union with a common external tariff-and provide a much-needed boost to Europe's economy. These are equally desirable goals, not only from the standpoint of EU federalists, but for proponents of a minimalist, free market version of the EU as well. However, in order to move forward with the Directive in the face of widespread opposition, the EU should implement the plan in increments, opening up the least controversial service occupations before moving on to sector-wide liberalization.

Waiting for the Single Market

The eight Central and Eastern European countries that joined the EU in May 2004 had good reason to believe that their citizens would be able to buy, sell and work freely in Western Europe once they were members. Under its founding treaty, the EU guarantees the free movement of goods, capital, labor and services. Achieving liberalization in these four areas is the core goal of the European Single Market that is the heart of the EU economic project. Despite frequent political setbacks and long periods of delay, the EU has made gradual progress in implementing the Single Market:

- In 1968, the market for goods was liberalized.

- In 1988, after a long hiatus, the capital market was liberalized.

- In 1993, the Western European labor market was liberalized and a strategy was developed for completing the Single Market.

On the eve of enlargement, Eastern Europeans assumed-not unreasonably-that this steady progress towards liberalization would continue once they were part of the EU. Nor did they have any reason to doubt they would enjoy full access to those elements of the Single Market already in place. After all, during previous rounds of expansion in 1986, the EU rapidly absorbed Portugal and Spain, giving them membership privileges with little delay. And given the region's comparative advantage in lower wages and skilled labor, Easterners especially looked forward to gaining greater access to Western European job markets â€" the main reason many wished to join in the first place. It therefore came as a surprise when, shortly before the accession process was complete, all but three of the EU's Western members states closed their borders to Eastern European workers. These moratoriums on labor movement will last up to seven years.

In the Meantime…Services Liberalization

The moratoriums were introduced to prevent people from the East from relocating to the West and taking up long-term residence. With the flow of labor blocked, the EU Commission turned its attention in 2004 to the market for services. Unlike the flow of general labor, the services sector is made up of a narrower range of specialized occupations, including business-to-business activities like accounting, consulting, advertising and construction, and business-to-consumer activities like hotels, restaurants, electricians, plumbers and florists. The services sector is the most important and fastest growing segment of the European economy:

- Job creation is faster in services than in any other segment of the European economy.

- Altogether, services account for 67 percent of EU jobs and 70 percent of its GDP, making this sector the largest contributor to European employment and wealth.

Despite its importance to the economy and a general willingness to liberalize in other areas like goods and capital, Europeans have been slow to open up the market for services. In an effort to protect home markets from foreign competition, EU member states employ a wide range of administrative barriers, regulations, licenses and fees. According to a recent report by the EU Commission, a European company attempting to set up shop in another EU country faces, on average, 91 different regulatory hurdles.1 These obstacles not only apply to companies that want to establish a permanent presence in another member state, but also to companies that want to provide services remotely from their country of origin. As a result of these barriers, the service industries, which account for 70 percent of EU GDP, account for only 20 percent of the trade between EU member states.

The Services Directive.

The idea behind the Services Directive is simple: By making it easier for service providers to operate across borders, the EU will be able to increase cross-border competition and productivity, spurring Europe-wide economic growth. The plan has two main components:

- The freedom of establishment clause. Companies or individuals providing a service in one EU country cannot be prevented from setting up shop in any other EU country.

- The country of origin clause. Companies or individuals from one EU country may provide services to consumers in another EU country on the basis of the laws of the home country, rather than the host.

The first provision would require national governments to remove the red tape that favors local service providers and excludes companies from other member states. Under the second provision, companies would no longer have to comply with different sets of laws for each of the countries in which they operate-a practice that can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars.

What Proponents Say.

Basic economic theory shows that opening up the services market would bring substantial benefits for the European economy.

- Removing barriers to competition forces countries to specialize in areas in which they have a comparative advantage.

- This in turn results in a more efficient allocation of national resources, which creates new jobs, lower prices, and greater choice and quality of services.

Studies conducted by the Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis and Copenhagen Economics have found that, by increasing the volume of cross-border trade by as much as 35 percent, the Directive would:2

- Increase EU GDP by between 1 and 3 percent.

- Boost consumer spending by €38 billion ($45 billion).3

- Increase wages by 0.4 percent.

- Drive down the price of services by about 7 percent.

Over the short term, the studies found that implementing the Directive would create around 600,000 jobs. The EU Commission predicts that over the long term, the proportion of the European workforce employed in the services sector would increase to U.S. levels, creating as many as 36 million jobs.4

Benefits for Eastern Europe.

For the economies of Central and Eastern Europe, liberalizing the EU services market would bring jobs, increased productivity and higher wages.

- Compared to Western Europe, a relatively lower percentage of the Eastern European labor force (around 50 percent) works in services, while a much higher percentage (in some places, 20 percent) is employed in agriculture.

- The Directive would create hundreds of thousands of new jobs, which would reduce unemployment and provide alternatives to agriculture.

- In addition to opening up jobs in Western markets, the Directive would also make it easier for Western European companies to set up shop in the new member states, creating jobs and spurring growth.

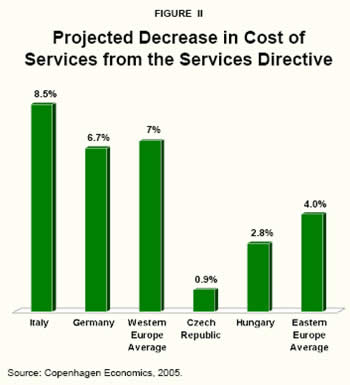

- The Directive would increase wages by about 0.3 percent (see Figure I), lower the costs of services by about 4 percent (see Figure II) and increase consumer choice â€" all of which would more than offset any job losses it causes.

Altogether, the Directive could increase Eastern European GDP by as much as €25 billion ($30 billion). Over time, this boost would help offset the costs that these countries incurred during the EU accession process, which Brussels has been slow to reimburse.

Benefits for Western Europe.

The benefits of services liberalization for Western Europe would outweigh its costs.

- In Western Europe, the intra-EU trade in services has not increased since 1992. By increasing cross-border trade by 35 percent, the Directive would provide a windfall for export industries, with a €20 billion ($24 billion) per year boost for German exports alone.

- Western European consumers would benefit from the reduction in the price of services. A study from Dublin found that the savings to Irish consumers alone would be almost €418 million ($500 million) a year.5

- Rather than a mass influx of unskilled laborers, the Directive would attract skilled craftsmen from professions Western Europeans tend to shun. In France, it would help fill the shortage of plumbers (about 6,000 are needed) and in Germany, it would help fill the shortage of construction workers.

Overall, the Directive could increase Western European GDP by as much as €230 billion ($275 billion).

Potential Costs of Liberalization.

Critics of services liberalization argue that the Directive would lead to economic and social disruption-especially in Western Europe:

Mass migration. Many Western Europeans fear that the Service Directive's softening of labor restrictions will lead to a sudden surge of Eastern workers migrating westward in search of better paying jobs. This is an especially acute concern in Germany, which-with its already large immigrant population, geographical proximity to the accession countries and 11 percent unemployment rate-would be unable to absorb a significant increase in labor supply.

Wage depression. Western Europeans also fear that larger numbers of workers will lower wages. Accustomed to meager pay back home, Eastern Europeans will gladly accept less than their Western European counterparts. In fact, this is already happening in parts of Germany, where Polish factory workers are replacing Germans for a fraction of the wages. To whatever extent the Directive brings about small net gains in employment (in Germany, 0.3 percent), most of these new jobs would be taken up by the Eastern European newcomers.

Uneven qualifications. Many of the barriers that the Directive would tear down in pursuit of freer trade are rules that were developed to guarantee consumer safety, quality and employee protection. By allowing Easterners to operate under the less stringent standards that apply in their home countries, many Western Europeans fear the Directive's "country of origin" principle will open the way for inferior, defective or even dangerous products and services-like electricians who install unsafe electrical wiring or doctors who prescribe the wrong dosage of drugs.

Overwhelmed social services. Another concern-especially for the elderly-is that incoming Eastern European workers will over-burden Western Europe's already strained social welfare programs. Those Easterners who find work will pay into their systems back home, while those who remain jobless will demand benefits from the host state.

In a word, Western Europeans fear the Directive because it would lead to what they see as unfair competition on both an individual and a national level. At an individual level, Western workers-with their rigid professional guilds and sector-wide wage agreements-would find themselves at a disadvantage to the more flexible Easterners. At a national level, Western companies would find it difficult to compete with Eastern rivals who pay lower wages and lower taxes and are less burdened by regulatory constraints. The end result would be a "race to the bottom," with companies migrating to countries with the lowest operating costs and poorest standards. To even the playing field, French and German politicians have called on the EU Commission to "harmonize" everything-qualifications, wages and welfare benefits-to the highest (Western European) levels.

Answering the Critics.

Though predictions about the negative effects of services liberalization are often exaggerated, they stem from legitimate concerns about how the Directive will impact the lives of everyday people. Clearly, the increased specialization and competition brought about by opening up the services market will require an adjustment period, during which there are sure to be both winners and losers. Nevertheless, the available evidence suggests that there will be more winners than losers and that the benefits of creating a freer market will far outweigh the costs.

Moderate migration. Economists say that, even if the entire EU labor market were liberalized tomorrow, the total number of Eastern Europeans migrating westward would be between 70,000 and 200,000 per year-two-thirds of whom (45,000 – 133,000) would go to Germany.6 To put this in perspective, about 230,000 Eastern Europeans already enter Germany every year under temporary working arrangements.7 Since the Services Directive would result in a far smaller influx of workers than general labor market liberalization, fears about it unleashing an Eastern exodus seem unfounded. Furthermore, the only Easterners allowed to move westward under the Directive will be those who already have stable jobs: pre-existing employees of a service company who are seconded to a new post in Western Europe, those who are hired and sent there directly, or those (like plumbers) who set up shop in the West as small businesses. Restrictions on workers migrating to the West are much more strenuous than the critics would have the public believe.

Wage increases. Contrary to widespread misconception, the Directive's "country of origin" principle does not apply to wages, which means that Eastern service providers will have to pay employees according to local minimum wage rates. And while the wage increases envisioned by the Danish and Dutch studies are modest, none of the EU member states-with the exception of Cyprus-is predicted to undergo a wage decrease.8 In fact, it is significant to note that, according to the Copenhagen Economics study, Western European countries will experience the largest wage increases, with a 0.7 percent increase forecasted for the Netherlands and UK (compared to a high of 0.4 percent among the Eastern Europeans).9

Qualifications. The minimum qualifications necessary for service companies to operate in Eastern Europe are usually assumed to be lower than those in Western Europe. However, this is an assumption; so far, there has not been a systematic study comparing standards in the two regions. Further, the controversial "country of origin" principle is already in use in the market for goods, where countries have long been required to accept products that meet the standards of other member states. To date, there have been no complaints about the quality or of Eastern European products on the Western market. And while Westerners fear a decline in health and safety standards, the Directive already contains language allowing countries to regulate and restrict services that do not meet national requirements.

Social services. Public fears about Eastern workers siphoning off social benefits have not been borne out in those Western member states where labor moratoriums were not imposed. In the UK, a recent government report showed that, in the first year after accession, the newcomers made "very few demands on public services."10 Out of 176,000 Eastern European immigrants, only 1,200 applied for income support and 8,148 applied for child benefits. Moreover, both the UK and Denmark have allayed public fears by creating two-tiered welfare systems, with separate benefits packages for natives and foreign workers. In Denmark, the government is actually using the situation to its advantage, requiring Eastern European workers to pay into the Danish welfare system without being able to draw benefits.

In sum, there are good reasons for Western Europeans to re-think many of their assumptions about the Services Directive. While a number of questions remain to be answered, the available evidence indicates that opening up the Western markets to Eastern competition would not bring about as dramatic a shock to the system as many labor union leaders and politicians believe. This evidence includes not only the findings of academic studies, but the experiences of those countries where an Eastern European labor presence is already a reality. It is true that countries like Germany-which are closer to Eastern Europe-have more to lose from opening their markets to the East. However, the UK has already absorbed more Eastern workers than Germany was forecasted to receive had it opened its borders, and the result has been an unambiguous boon for the British economy: Between May 2004 and May 2005, Eastern European workers contributed €746 million ($892 million) to British GDP.11 As Tony McNulty, the UK Immigration Minister, said, "These workers are contributing to our economy, paying tax and national insurance and filling key jobs in areas where there are gaps."12

Averting Demographic Decline.

A final benefit of services liberalization-and of Eastern European labor mobility more generally-is that it may indirectly help to alleviate Western Europe's aging crisis.

- According to the United Nations, Europe's fertility rate is 34 percent below the replacement level and 40 percent lower than the United States'.13

- By 2050, Italy's population will fall from 58 million to 45 million, while Spain's population will drop from 40 million to 37 million. By the end of the century, Germany's population could fall from 80 million to 25 million.14

- By 2050, nearly 40 percent of Europeans will be over 60 years old, compared to 22 percent today.

The Eastern expansion increased the EU's population by 20 percent. Significantly, 67 percent of the 75 million Eastern Europeans coming into the EU are working age (15 to 67 year olds). Looking forward, Western Europe will need these workers to provide public pensions for an increasingly large number of retirees.

- In Western EU countries there are currently 35 pensioners for every 100 workers. By 2050, this ratio will have changed to 75 pensioners for every 100 workers.15

- In Italy, the ratio of workers to pensioners will be 1:1 within 25 years.16

- In Germany, by 2050 there will be as many citizens over the age of 80 as citizens under the age of 20.17

To offset the negative impact of aging on their economies, Western European countries need a large influx of foreign workers. Although the Services Directive will not provide the numbers of young workers necessary to solve the problem, it is a move in the right direction, one that could eventually open the way for full scale labor mobility. Far from destabilizing the Western European welfare state and economy, Eastern European workers represent an important means by which they may be preserved and strengthened.

Conclusions and Recommendations

This brief overview of the Services Directive debate prompts a number of important observations.

Conclusions.

First, from a public relations standpoint, there is clearly a critical need on the part of the European Commission for more and better information on the likely effects of services liberalization and a greater effort to calm public fears and explain the need for the Directive. Outreach of this kind has been conspicuously absent from the EU policy-making process and is largely responsible for the widespread feeling of disconnect between the EU and European voters.

Second, from a public policy standpoint, there is a need for more compromise and less fear-mongering-especially on the part of labor unions and left-of-center politicians. For countries like France and Germany that are nervous about opening their economies to foreign competition, there is much to learn from those countries where the labor markets have already been liberalized. The experiences in the UK and Denmark not only show that the negative side effects associated with Eastern labor migration are not occurring on the scale anticipated, but also that, to the extent there are problems, they are made more manageable by transitional arrangements-like the two-tiered welfare system. Rather than attempting to block the Services Directive altogether, the French and Germans should imitate the British and develop innovative strategies that allow them to harness the positive forces of liberalization while minimizing its negative side-effects. Doing so would enable them to keep their current systems while benefiting from the lower price of services across Europe. This kind of approach is preferable to the alternative-"harmonization"-which would place an unsustainable tax and regulatory burden on Eastern Europe while doing nothing to alleviate the growing economic malaise in Western Europe.

Third, from an overall economic standpoint, Western European leaders must recognize that, in a global economy where open service markets are increasingly the norm, resisting liberalization at home in deference to organized labor and local political interests is no longer an option. In the context of globalization, regardless of whether one supports a centralized EU or a looser federation of European states, the future for Europe lies in less protectionism and regulation. Already, the EU's failure to open borders internally is having a devastating effect on European competitiveness in global markets. According to a recent French study, by 2050, the EU's share of the world economy will shrink from its current level of 22 percent to 12 percent and its growth rate will drop to 1.1 percent (compared to 2.3 percent in the U.S. and 2.6 percent in China).18 In such an environment, Europe cannot afford fragmentation and inefficiency in a sector that makes up 70 percent of its GDP and jobs, and represents its main engine for economic growth.

Finally, for the new EU member states of Central and Eastern Europe, the debate over the Services Directive underscores the need for a critical re-evaluation of the EU's purpose and the terms of membership. For more than a decade, these countries undertook difficult and costly reforms that were required in order to join the union. In return, Brussels promised to: (a) cover the costs of accession and (b) give the newcomers the same rights and benefits as the other member states. However, in the wake of accession, Eastern Europeans have received only a fraction of their promised reimbursement and are slated to receive a small fraction of the subsidies already provided to new members in previous rounds of enlargement. By depriving the newcomers of aid while simultaneously refusing to allow the liberalization that would enable them to survive without it, the Western Europeans are creating a state of affairs which, from an Eastern European standpoint, is economically untenable. For the people who live in the new member states, the effort to defeat the Directive-coming as it does on the heels of the French backlash against the "Polish plumber" and the closing of Western borders to Eastern workers-has the appearance of an attempt to impose second-class membership and raises serious questions about the EU's reliability as an honest broker, as well as its ability to live up to its commitment to free trade under its founding treaty.

Recommendations.

For all of these reasons, the European Parliament would be well-advised to approve the Services Directive when it comes up for a vote in late 2005. Significantly, both the current EU Council President-British Prime Minister Tony Blair-and the EU Commission President-free market reformer Jose Manuel Barroso-are in favor of the legislation. However, in light of the widespread opposition the Directive has encountered throughout Western Europe, EU policymakers may find it expedient to introduce the plan in stages, rather than opening up the services market all at once. If the French and Dutch referendums shared a common theme, it was a desire on the part of many Europeans to slow down the movement toward European unity and proceed in a more cautious, incremental fashion. For services liberalization, this may mean opening up the more closely regulated, business-to-business occupations-like accounting, advertising and consulting-first, and leaving the other, more politically sensitive service jobs-like plumbers and electricians-for a later date.

Implementing the Directive in this sort of piecemeal fashion may offer the best chance for achieving services liberalization and help lay the groundwork for an eventual opening up of the entire labor market. For the time being, the EU should commission further research into the question of which occupations would be the least painful to open up to competition. Over time, liberalizing services-even in stages-could help restore the EU's credibility at a moment when that is in short supply and bring the union one step closer to fulfilling the most important purpose of its existence-the creation of a functioning single market. In so doing, the EU may yet be able to escape its current state of economic atrophy and re-establish itself as a vibrant force in the global economy. Regardless of the political form the EU eventually takes, this is a goal upon which everyone should be able to agree.

Wess Mitchell is a senior policy analyst at the Center for European Policy Analysis.

NOTE: Nothing written here should be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of the Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA) or the National Center for Policy Analysis (NCPA) or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before Congress.

Notes

- Report from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament on the State of the Internal Market for Services, July 30, 2002.

- Economic Assessment of the Barriers to the Internal Market for Services, Copenhagen Economics, January 2005; Henk Kox, Arjan Lejour and Raymond Montizaan, "Intra-EU Trade and Investment in Service Sectors, and Regulation Patterns," CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis, CPB Memorandum No. 102, November 2004.

- Euro-U.S. dollar equivalents throughout based on the October 5, 2005, exchange rate of US$1 to €0.8358, as published in the Wall Street Journal.

- "Services: Commission Launches New Strategy to Dismantle Remaining Barriers," European Commission Press Release, January 11, 2001.

- Ronnie O'Toole, "The Services Directive: An Initial Estimate of the Economic Impact on Ireland," Forfas, February 28, 2005. Available at http://www.entemp.ie/trade/marketaccess/singlemarket/05serv099.doc.

- "The Free Movement of Workers in the Context of Enlargement," European Commission, March 6, 2001, page 8.

- "The Free Movement of Workers in the Context of Enlargement," European Commission, March 6, 2001, page 6.

- Economic Assessment of the Barriers to the Internal Market for Services, Copenhagen Economics, January 2005, "Appendix A: Detailed Results from the CETM Model," page 4.

- Ibid.

- Richard Ford, "176,000 Migrants from Eastern Europe Seek Jobs in First Year," (London) Times Online, March 27, 2005.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ben Wattenberg, "Counting Change in Euroland," Washington Times, January 28, 1999.

- "Europe's Population Implosion," Economist, July 17, 2003.

- Ibid.

- Ann Mettler, "Europe's Forgotten Youth," Wall Street Journal, August 11, 2005.

- Ibid.

- "World Trade in the 21st Century," Institut Francais des Relations Internationales (IFRI), May 2003.