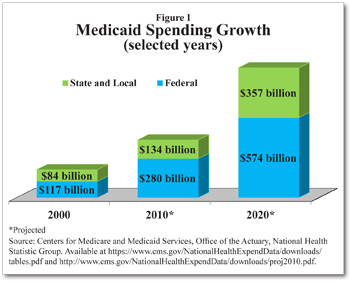

Medicaid is a health program for the poor and disabled funded by federal and state appropriations. It is the largest and fastest growing publicly funded health program in the United States. Indeed [see Figure I]:

State and local government Medicaid spending is projected to rise rapidly from $130 billion in 2009 to $357 billion by 2020.

Federal Medicaid spending is projected to increase from $254 billion in 2009 to $574 billion by 2020.

Total Medicaid spending is expected to rise to $930 billion by 2020 and will account for 20 percent of all U.S. health expenditures.

There are two major reasons for this growth. One is that the federal government matches all state spending on federally allowed Medicaid services. This encourages excess spending. The second reason is the program’s complexity. There are seven specific groups of people that state Medicaid plans must cover, and any combination of nine optional populations states have the option to cover. There are 13 mandatory service categories that must be covered and states can add any combination of 17 optional services.

States can also apply for federal Medicaid waivers that allow them to test policy innovations, to limit enrollees’ choice of individual provider, and to provide long-term care services in a community setting.

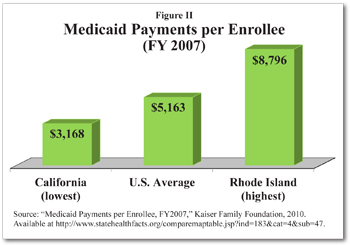

Waivers, state spending differences, coverage of mandatory and optional populations and services combine to ensure that no two states have exactly the same Medicaid program. For example, as of July 2007, maximum annual income Medicaid eligibility thresholds for a family of three with one working parent ranged from $3,360 in Louisiana to $47,232 in Minnesota. Medicaid payment rates also vary. In 2001, for example, fees to a physician performing an appendectomy ranged from $160 in New York to $799.87 in Nevada. Thus, the average cost per Medicaid enrollee was $5,163 in 2007, but varied from $3,168 in California to $8,796 in Rhode Island. [See Figure II.]

If Medicaid were turned into a block grant program in which the federal government gave each state a set amount of money, it could improve patient care, restrain the growth in costs, reduce complexity and improve outcomes. Furthermore, block grants could be used to implement consumer-directed reforms that allow Medicaid enrollees to control some of the spending on their care and give them incentives to avoid unnecessary care.

If Medicaid were turned into a block grant program in which the federal government gave each state a set amount of money, it could improve patient care, restrain the growth in costs, reduce complexity and improve outcomes. Furthermore, block grants could be used to implement consumer-directed reforms that allow Medicaid enrollees to control some of the spending on their care and give them incentives to avoid unnecessary care.

Perverse Incentive of Free Care. Individuals who pay almost nothing for their health care have little incentive either to economize their use or to seek less costly ways to receive it.

For example:

Nationwide, between 1997 and 2007, the total number of hospital emergency room (ER) visits each year doubled, mostly due to the increased frequency of use by adults with Medicaid coverage.

In 2006, Medicaid enrollees accounted for 26 percent of all U.S. ER visits.

At least some Medicaid adults use the emergency room because it is convenient and costs no more than a regular physician visit.

When Oregon implemented $50 copays on ER visits under a Medicaid waiver in 2003, ER utilization rates fell 18 percent and visits leading to hospitalization fell 24 percent.

Disincentives to Deter Fraud.Some experts estimate that fraud and abuse accounts for 10 percent of Medicaid spending. Common fraud problems among Medicaid providers include charging for medical, transportation and home health care services that were never delivered, charging for a more expensive service or good, using ambulance transportation when it is unnecessary, and charging twice for the same treatment. Because other people are paying for their health care, Medicaid recipients have little reason to detect and deter fraud.

Furthermore, matching funds make fraud control less enticing for states. For example, with a 50 percent match rate, if a state spends $1 to reduce fraudulent Medicaid spending by $2, the state loses $1 of the matching federal funding and its net gain is zero.

Matching fund finance also affects state incentives to verify the eligibility of enrollees. In response to strong evidence that states were adding illegal aliens to their Medicaid rolls, the 2006 federal Deficit Reduction Act required states to demand proof of citizenship as a condition for Medicaid enrollment. In 2007, the number of non-disabled adults and children enrolled in Medicaid declined for the first time since 1996.

Block Grants and Welfare Reform. Federal block grants consolidate various aid programs into a payment to each state based on a formula set by law. This eliminates the ability of federal agencies to allocate grant funds to favored applicants, establish program priorities and set requirements. Block grants give the states increased flexibility to experiment, improve programs and allocate funds to their priorities.

Block grants do not require states to match the federal funds with their own spending, eliminating the incentive to spend more in order to maximize the federal subsidy. Federal oversight focuses on ensuring that state plans for using federal money are complete and comply with statutory requirements. Detailed reviews of proposed programs are not required.

Welfare reform is an example of a successful block grant program. In 1996, the Aid to Families with Dependent Children entitlement program was replaced with the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) block grants. The switch to TANF block grants had generally positive effects on employment, earnings and income. As states changed the structure of benefits to reward work, funds were shifted from cash assistance to child care, housing, transportation and education. A million children moved out of poverty as work effort increased and caseloads fell more than 60 percent.

Consumer-Directed Medicaid Reforms. Consumer-directed health care is based on the simple idea that when people spend what they think of as their own money on their own health care, they spend less and get more than if they spend other people’s money. For example:

In the private sector, switching to health insurance policies that have lower premiums but require people to spend more out of pocket on routine care appears to reduce expenditures by 4 to 15 percent in the first year. It reduces annual spending growth rates by 3 to 5 percent thereafter.

The classic RAND Health Insurance Experiment showed that expenses were 45 percent higher with free care than under a plan that required people to spend their own money for 95 percent of the cost of care up to a deductible limit equivalent to about $4,000 in 2011 dollars.

Cost-sharing reduced health expenditures by both the poor and non-poor, with similar health outcomes for both groups.

The benefits of consumer-directed care for Medicaid populations have been confirmed by several experiments.

Cash and Counseling. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Cash and Counseling experiments in four states from 1999 to 2003 gave disabled Medicaid recipients a budget to hire the attendants of their choice to provide care in their homes. Before the experiment, disabled Medicaid recipients had no say in who came to their homes, what they were paid, when they came or what they did. During the experiment, recipients could hire and fire their caregivers, set their wages, and determine their hours and terms of employment.

Consumer direction reduced rates of unmet need, theft and injury. Though individuals purchased fewer hours of attendant care overall, they were more satisfied. In fact, patient satisfaction was almost 100 percent. In the second year of the experiment, Medicaid beneficiaries in Cash and Counseling spent fewer days in nursing homes and had fewer home health therapy visits. Although Cash and Counseling was designed to be budget neutral, expenditures increased 28 percent in Arkansas simply because the state had set payment rates so low that Medicaid could not find workers in some areas. Cash and Counseling’s wage flexibility allowed the disabled to receive the care they were promised.

Healthy Indiana. The Healthy Indiana Plan (HIP) seeks to give Medicaid enrollees an incentive to take care of themselves and to reward them for spending program dollars wisely. Participants have a choice of three health plans, all of which have a $1,100 deductible. The deductible is funded by a Personal Wellness and Responsibility (POWER) account. Enrollees must make monthly contributions to their POWER account if their income is above the poverty level. The state contributes to accounts for lower income members. Participants who have received required preventive care can use the balance remaining at the end of the year to reduce the next year’s premiums. The HIP covers $500 in preventive care services and there are no copays, except a $25 charge for non-emergency ER use.

HIP retention rates have been higher than in Indiana’s regular Medicaid program. Less than 3 percent of members left because they failed to pay monthly contributions. Of those who enrolled in the first six months, 36 percent had funds to roll over and 71 percent met the preventive care requirements. There are preliminary indications that emergency room use has declined despite the fact that early enrollees may have had greater than average medical problems.

Rhode Island Block Grant. Rhode Island has been experimenting with a Medicaid block grant since January 2009. In exchange for more flexibility, Rhode Island agreed to a $12.075 billion limit on all federal Medicaid matching funds through 2013. In 2010, the second year of the new program, state Medicaid spending was $1.34 billion below the budget neutral target of $2.4 billion.

Rhode Island sought flexibility in order to focus on patients as people with diverse needs. As a result of a meticulously planned transition, in its first two quarters of operation the state managed to eliminate waiting lists for long-term services. It also moved 93 people from nursing homes to home care. The state developed a needs-based system to determine the safest and least restrictive setting of care for people needing long-term care. It provides homemaker services, minor home modifications, respite care and physical therapy when such care allows an individual to stay in their home or delays nursing home placement.

Unlike traditional Medicaid, the Rhode Island experiment requires able-bodied people with incomes above 150 percent of the poverty level to contribute toward their health coverage. For Medicaid-eligible families who also have access to employer-sponsored health insurance, the state pays all or some of the employee’s cost.

Consumer-Directed Attendants in Colorado. In Colorado, disabled Medicaid recipients worked closely with state officials to develop the Consumer Directed Attendant Support Services (CDASS) pilot program, which began operating in 2002.

CDASS was similar to Cash & Counseling in outlook, but was not designed to be budget neutral and gave participants a stronger incentive to use their dollars wisely. Before CDASS, Medicaid contractors sent attendants to homes and billed the state. Since Medicaid beneficiaries never saw the bills, the state did not know whether an attendant had actually shown up and done satisfactory work. With CDASS, the people paying for the services knew exactly what they were getting. If participants had money left over at the end of a year, they shared the savings with the state on a 50-50 basis. With their health care at stake and a share in any savings, CDASS participants had a low tolerance for fraud or incompetence.

In its first two years, beneficiary health improved and spending was 21 percent under budget. The waiver authorizing the pilot program ended after five years. The state and federal officials fashioned a program extension, but Medicaid officials have ended the practice of sharing savings with patients, the state is trying to control the wages participants can pay and program operation has been hampered by poor administration.

Options for the Future. Block grants can change Medicaid incentives by eliminating matching fund finance. States satisfied with their current Medicaid program could continue without change just by meeting a negotiated budget. States that think they could do better would be free to try something else. The federal government would manage one Medicaid block grant program rather than 50 different state Medicaid experiments.

Reforms that give individuals an incentive to spend wisely, and that give states flexibility in return for an end to unlimited federal matching funds, have produced promising results. Making Medicaid a block grant program would allow states to build on that promise.

Linda Gorman is a senior fellow with the Independence Institute.