Medicaid, the joint federal-state health care program for the poor and near poor, is the largest single expenditure by state governments today. At the rate the program is growing, it is on a course to consume the entire budgets of state governments in just a few decades.

Although Medicaid is commonly assumed to be a health program for welfare recipients, there are ten times as many people on Medicaid as there are receiving welfare checks. Medicaid now costs American taxpayers more than Medicare, or more than $1,000 per year for every man, woman and child in the country. The tax burden for both programs combined is more than $8,000 a year for the average family of four. Nationally, Medicaid now covers:

- One in every six people.

- One in every three children.

- One in every two births.

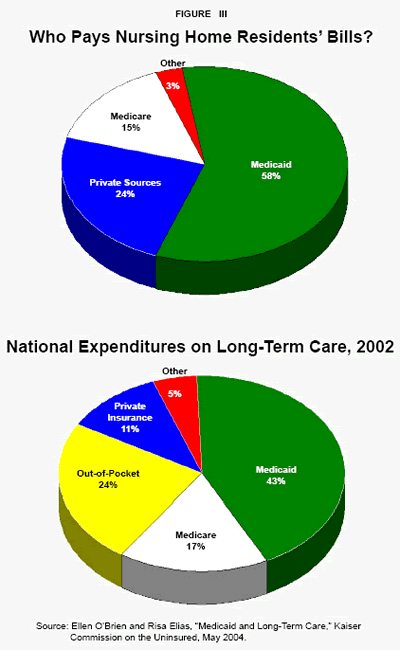

More than one of every two nursing home residents.

New York’s Medicaid program is especially costly. New York has less than 7 percent of the U.S. population, but spends about 14 percent of the nation’s Medicaid dollars. In 2004, the latest year for which complete data is available:

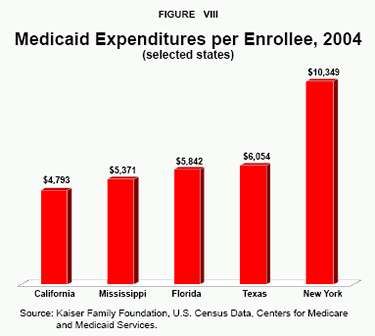

- New York spent $10,349 per enrollee, compared to the nationwide average of $6,834. Only New Hampshire spent more.

- New York Medicaid spent about $2,165 for each state resident (more than any other state) and almost two-and-one-half times the national average.

Why Is New York’s Medicaid Program so Costly? Higher living costs do not account for the high Medicaid spending in New York. The state spends more because of policies that encourage higher spending and discourage cost control. Other states share some of these same problems, but none have such a wide array of perverse incentives. Specifically:

- Unlike most other states, New York offers coverage to virtually all optional populations, and covers almost all optional services.

- New York pays physicians less than almost any other state, even though physician therapies are often more cost effective than hospital therapies.

- In contrast to its treatment of physicians, New York pays hospitals generously; whereas in most states Medicaid pays the lowest hospital fees of any payer, in New York Medicaid pays the highest fees of any payer — including private insurers.

- New York does not use smart buying techniques, such as selective contracting with providers, to reduce costs.

- New York spends more than any other state on drugs and pays some of the highest drug prices of any state; the state imposes few restrictions on doctors who prescribe the most expensive drugs, when lower-cost alternatives are often just as effective.

- The political incentives to spend are greater since the New York legislature bears only a fraction of the cost (less than almost any other state); for every dollar the state spends, it can confer $4 of benefits.

- New York does not aggressively pursue fraud — even failing to spend a substantial portion of the federal funding available for antifraud efforts; in 2004, only 37 cases of suspected fraud were uncovered.

- New York’s insurance regulations raise the cost of private insurance, and make (free) Medicaid coverage more attractive.

- While personal and home care substitute for institutional care in other states, New York spends more than most states for all three, and a fourth of all Medicaid dollars spent nationwide for personal care are spent in New York!

If New York Medicaid were as efficient as the average state program, it could spend billions of dollars less to achieve the same health outcomes, and would have billions of dollars each year to fund tax cuts or other spending programs.

What Can New York Do to Improve Medicaid and Control Costs? New York can control costs and improve services, by adopting common-sense reforms; by contracting with private sector providers for services; by fundamentally restructuring its program; and by moving patients out of Medicaid and into private sector plans. As part of this reform effort, the state also needs to completely overhaul long-term care and home health services. The common-sense reforms include:

- Negotiating discounts for most medical services through selective contracting.

- Treating patients in outpatient settings, such as doctors’ offices, where medically appropriate.

- Paying higher fees to physicians to increase patients’ access to health care and reduce expensive emergency room visits.

- Controlling drug costs using private-sector techniques, including pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs).

- Setting up cash accounts that disabled Medicaid recipients can use to manage their own health care dollars and take direct control over the purchase of needed services.

- Adjusting payments to hospitals to reward facilities that achieve low infection rates and reduce errors.

- Coordinating care to improve its quality and reduce medical errors, such as drug interactions, and instituting disease management, which involves developing treatment plans based on current protocols and training patients how to the follow them.

- Pursing fraud aggressively by giving local governments the authority to prosecute fraud and financial incentives to recover payments.

Structural reforms are also needed. Local governments, including counties, pay about 25 percent of the cost of Medicaid, and the federal government pays more than half. Since Medicaid spending is determined by the state government, the way the program is financed violates the principle that those who spend the money should bear the responsibility of paying for it. One solution is to block grant the funds to local governments, and let them locally manage their own Medicaid dollars.

Insurance market reforms are also needed. One reason so many people turn to Medicaid is that they have been priced out of the market for private health insurance by cost-increasing regulations. New York insurance laws allow people to obtain insurance once they become ill (guaranteed issue) and require insurers to charge the same price regardless of age and health status (community rating). This encourages people to remain uninsured until they get sick and causes the cost for those who need insurance to be way too high. A better way is to establish high-risk pools like those now available in 32 states.

New York is one of four states with a pilot project that provides financial incentives for people to purchase long-term care insurance. When the insurance is exhausted, special eligibility rules allow them to receive Medicaid benefits while retaining assets equal to the value of the policy. This is a good program with a worthy goal. But compared to other states, New York’s rules are too restrictive. Also, the state needs to give people financial incentives to choose (less-costly) home care over nursing home care. Other financing mechanisms also should be encouraged, including reverse mortgages, home sales contracts and viatical settlements.

How Can We Empower Medicaid Enrollees? A more fundamental reform is the creation of cash accounts that enrollees use to pay out-of-pocket costs. About half the states have cash and counseling pilot programs under way, allowing disabled Medicaid enrollees to manage some of their own health care dollars. (Patient satisfaction is near 100 percent!) Florida and South Carolina are about to integrate such accounts into their regular Medicaid programs.

What Is the Alternative to Medicaid? The ultimate goal of Medicaid reform should be to move patients to the same type of private health plans most Americans have. Private-sector plans may appear less generous on paper than the current Medicaid program, but they usually allow enrollees to access a greater range of providers and facilities. Enrollees in a Florida pilot program, for example, will be allowed to use their Medicaid funds to pay premiums for employer-sponsored plans where they work. New York Medicaid patients should also be allowed to enroll in the same plans that cover state employees.

Some of these changes the state can make itself; others require waivers from the federal government. In either case, the state should move forward with reform. Without change, patient care will likely deteriorate, and the Medicaid Empire will sink the taxpayers of the Empire State.

[page]Medicaid is the largest single expenditure by state governments today. Costs rose rapidly over the past decade, and the country as a whole now spends more on Medicaid than it spends on primary and secondary education. 1 We also spend more on Medicaid (mainly for the poor) than we spend on Medicare (mainly for the elderly). 2 Medicaid and other health expenses already account for one in every five dollars of state spending, in addition to the burden on federal taxpayers.3 At the rate the program is growing, it is on a course to consume the entire budgets of state governments in just a few decades.4

It is sobering to realize that Medicaid alone costs more than $1,000 per year for every man, woman and child in the country — or $4,000 for a family of four. Since Medicare costs a comparable amount, the average family is spending about $8,000 on other people’s health care — an amount that for many is well in excess of what they spend on health care and health insurance for their own family.

“Medicaid is the largest single expenditure by state governments.”

There is a desperate need to restrain the growth of Medicaid spending. However, squeezing payments to providers or limiting coverage is not the best approach. The best alternative is fundamental reform that introduces choice and competition, and encourages private-sector coverage. Incremental steps toward these objectives would benefit Medicaid patients as well as taxpayers.

This study addresses problems in New York’s Medicaid program, surveys promising reforms currently underway in other states, and recommends a number of changes. Because Medicaid is a joint federal-state program, some fundamental reforms will require Congress to address the program’s future in a comprehensive way. But New York policymakers can make dramatic changes in program design and cost without new federal legislation.

[page]Medicare and Medicaid were created in 1965 at the height of President Johnson’s Great Society and War on Poverty. Medicare is a federally funded health care program for seniors and the disabled. Medicaid is a joint federal-state program for the poor and near poor. Although each state operates its own program, the federal government sets the parameters for Medicaid and matches state spending. Medicaid has grown far beyond the program originally envisioned and the scope of the current program is staggering. Nationally, Medicaid covers:

- One in every six people.

- One in every three children.

- One in every two births.

- More than one of every two nursing home residents.

The number of Medicaid enrollees nationwide rose by nearly one-third between 2000 and 2004.5 Currently at 53 million, the number is likely to grow much higher. There are 10 million to 14 million people who are potentially el`igible but have not enrolled.6 Additionally, the number of seniors who qualify for Medicaid long-term care benefits is projected to grow rapidly as the Baby Boom generation begins to retire. The population over age 65 will grow by nearly two-thirds (64 percent) by 2020, and the number of seniors over age 85 will grow by 84 percent by 2025.7

“Ten times as many people are enrolled in Medicaid as receive welfare.”

Although Medicaid is commonly assumed to be a health program for welfare recipients, only a small portion of enrollees receive Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), the main cash assistance program. Furthermore, the number of individuals receiving TANF has fallen from almost 13 million in 1996 to about 5 million in 2003; as a result, the proportion of Medicaid enrollees who are welfare recipients has also fallen.8 Surprisingly, there are ten times as many people on Medicaid as there are receiving welfare checks.

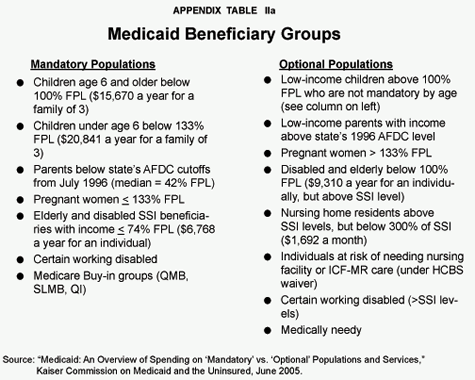

Who Qualifies for Medicaid? Federal law requires the states to cover certain populations, including low-income seniors and pregnant women, the blind and disabled, and all children living in poverty. The states `an choose to cover children and families above the poverty level. The states also impose their own asset tests to determine eligibility. In New York, for example, a Medicaid-eligible individual can own a home, a car and personal property.

Every state covers some optional Medicaid populations, which are currently about 29 percent of enrollees.9 New York, for instance, extends eligibility to include young children (ages one to five) in households with incomes up to 133 percent of the federal poverty level, and infants to age one and pregnant women with incomes up to 200 percent of the federal poverty level.

In theory, most seniors and most of the disabled are covered by Medicare, a wholly federal program paid for by the federal government. However, there is a class of Medicare recipients called dual eligibles. Although they qualify for Medicare, they can also receive Medicaid because of their low incomes and few assets. Medicare is the primary payer, but states must pay for any benefits Medicare doesn’t pay for if Medicaid covers them. More than one-third of all Medicaid costs are for dual eligibles.10

How Do Enrollees Get Medical Care? On paper, Medicaid coverage appears more generous than the health plans of most other citizens. Potentially, enrollees can see any doctor or enter any facility and have government pay virtually all costs. In practice, things are different.

Access to Primary Care. Physicians and other health care providers can choose whether or not to participate. About 30 percent of doctors do not accept any Medicaid patients, and among those who do, many limit the number of Medicaid patients they will treat. Access to care at ambulatory (outpatient) care clinics is also limited: A recent survey found two-thirds of Medicaid patients were unable to obtain an appointment for urgent ambulatory care. In three-fourths of the cases, the reason was that the provider did not accept Medicaid.11

Access to Specialists. The number of specialists who accept Medicaid is particularly limited.12 According to a recent New York Times series, for example:13

- In New York City, a child with an irregular heartbeat was not able to see a cardiac specialist for nearly four months.

- The parents of a boy needing corrective ear surgery were told the wait could be as long as five years.

- At specialty clinics run by teaching hospitals in the city, Medicaid patients often have to wait one to three hours for a 5 to 10 minute appointment with a less-experienced medical resident or intern.

The problem is not limited to New York:

- Physicians say the University of Colorado Hospital is refusing Medicaid patients, and Medicaid enrollees there can face six- to eight-month waits for appointments at specialty clinics.14

- A 45-year-old Seattle woman admitted to the hospital with a triple fracture of her ankle waited nine days for a doctor to agree to take her case, because none of the orthopedic surgeons on staff would accept Medicaid.15

“Medicaid appears more generous than private health plans, but access to care is more limited.”

Access Through Managed Care Plans. Medicaid managed care plans are one way the states have attempted to expand access to care, control costs and improve quality. The choice of physicians and facilities are limited to the providers in the plan (as in private insurance plans) but contractual arrangements between physicians and the plans ensure a degree of access that Medicaid patients typically do not have. Nationally, about 27 million Medicaid enrollees, 61 percent of the total, are in managed care plans.16 The percentage of Medicaid enrollees in managed care ranges from none in a few states to 100 percent in Tennessee. Of the 4 million Medicaid recipients in New York in 2004, 58 percent (2.3 million) were in managed care plans.17

Under routine Medicaid, health care providers are reimbursed according to fee schedules set by state administrators; and one reason so many doctors eschew the program is because fee payments are so low. Under managed care, however, the plans receive a set annual fee per enrollee to provide whatever health services the state covers and the plans can negotiate to pay providers higher fees than normal Medicaid rates.18

“Nationwide, one-fourth of Medicaid enrollees account for two-thirds of costs.”

In New York City, Medicaid managed care plans are operated by public hospitals, and outpatient care is provided by clinics and community health centers. Some of the provider networks only serve special populations, such as pregnant women, and once the women give birth, they must transfer to another network.19 Other states contract with networks created by the same private insurers who administer employer-sponsored health plans.20

“One-third of New York Medicaid enrollees account for three-fourths of costs.”

Alternatives to Managed Care. During the 1990s, large insurers and most employers turned to managed care as a way to control costs. One way or another, these systems tended to reward providers for cost control. Managed care has not proved popular with patients, however. Whereas fee-for-service medicine gives providers an incentive to overprovide services, HMO-type fixed payments create incentives to underprovide. All too often, patients viewed managed care as an impersonal bureaucracy that puts cost control ahead of patient welfare.21 We will explore Health Savings Accounts as an alternative to managed care below.

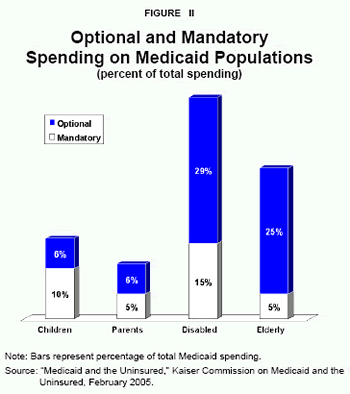

“Two-thirds of Medicaid spending is for optional benefits; one-third is for mandatory benefits.”

Where Do the Dollars Go? Roughly two-thirds of Medicaid spending nationwide is on optional populations and services:

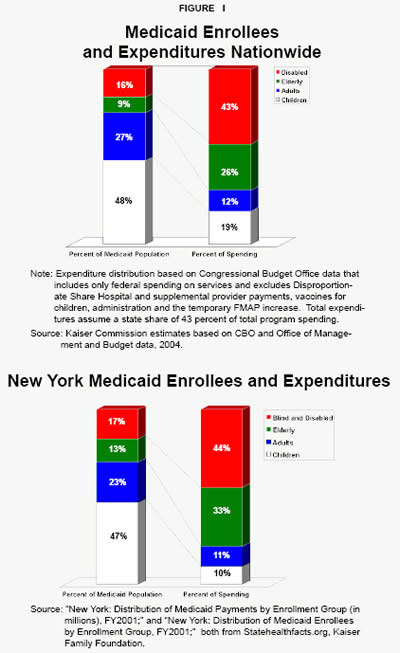

- The general public tends to imagine the program primarily serves poor women and children; however, although this group includes three-quarters of all enrollees it accounts for less than one-third of the funds spent.22

- By contrast, the elderly and disabled account for about one-fourth of enrollees but more than two-thirds of all costs. [See Figure I.]

“Medicaid pays the bills of a majority of nursing-home residents.”

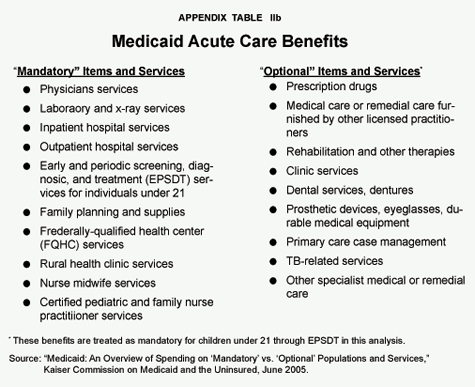

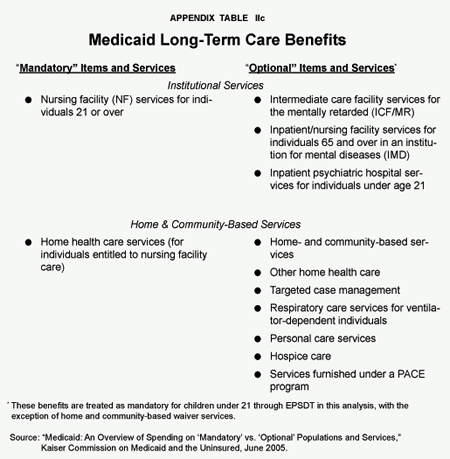

States have considerable flexibility to determine the types of services covered by Medicaid. The federal government requires every state to offer 14 mandatory benefits (for example, hospitalization, physician visits and so forth) but allows each state to choose which of 34 optional benefits it will cover, including prescription drugs, and long-term care. [See Appendix Table IIa-c.] Two-thirds of Medicaid spending is on optional benefits. [See Figure II.] 23

Nursing home care is an optional benefit that every state provides. Medicaid pays for 58 percent of all nursing home residents and 43 percent of all long-term care costs nationally. [See Figure III.] Long-term care is used by only 9 percent of all enrollees.24

“The distribution of federal Medicaid dollars does not reflect the distribution of poverty.”

How Is the Federal Contribution Determined? One might assume that the federal government’s Medicaid contribution is based on each state’s poverty population. This is not the case. Using the percentage of the nation’s poor that live in each state as an indication of need, many states receive far more Medicaid dollars than they should while others get far less. [See Table I.] New York, for example, has 8 percent of the nation’s poverty population, but gets 12.9 percent of all federal Medicaid dollars. By contrast, Texas has 10.3 percent of the nation’s poverty population, but receives only 6 percent of federal Medicaid dollars. As Figure IV shows, New York received 68 percent more than it would have based on the distribution of poverty alone.

- Vermont received more than twice as much as its portion of the poverty population.

- Maine received almost 97 percent more than it would based solely on the poverty distribution.

Among states that received far less than they should by this criterion:

- Virginia received only 69 percent of what it should have based on its share of the poverty population.

- Texas got about 57 percent of the funds it should have based on need.

- Nevada received only 51 percent.

Poverty versus Other Factors. Arguably, federal Medicaid spending should be based on more than the distribution of poverty.25 We should probably also consider ability to pay as well as differences in the cost of health care. Using state data on poverty, personal income per capita (as a proxy for ability to pay) and personal health expenditures per capita (as a proxy for health care costs), we performed a regression analysis of federal Medicaid dollars spent in each state. [See Appendix Table I.] It shows: 26

- A 10 percent increase in the poverty rate in a state increases federal Medicaid spending in a state by 8.2 percent.

- A 10 percent increase in per capita health expenditures increases federal Medicaid spending for a state by 12.6 percent.

- However, a 10 percent increase in a state’s personal income per capita has no effect on federal Medicaid spending.

“Some states receive far more federal dollars than if the money were distributed based on poverty.”

Based on our analysis some states are receiving far more or far fewer Medicaid dollars than would be indicated, taking into account all three factors. Texas should receive almost 9 percent of federal Medicaid dollars instead of its current 6 percent. By contrast, New York should receive only about 7 percent of total federal Medicaid dollars, instead of its current 12.9 percent.

The Federal Match Formula. What accounts for these disparities in the distribution of federal funds? The answer lies in a formula called FMAP (Federal Medicaid Assistance Percentage or the “federal match”) used to determine the percentage the federal government contributes to each state’s program.

The formula uses the ratio of per capita income in a state to per capita income nationwide (a proxy for both poverty and ability to pay) to determine the federal matching rate. However, there is a 50 percent floor on the federal matching rate and an 83 percent ceiling, designed to bring states closer to the national average in terms of their funding ability. A matching rate of 50 percent means that a state receives one dollar in federal funding for every state dollar spent. There is no limit on the number of state dollars the federal government will match; hence, states that spend more on Medicaid receive more federal dollars.27 [See Appendix I for a detailed explanation of the formula.]

“The federal matching formula rewards states that spend more.”

However, the matching rate is enhanced by an additional amount equal to 30 percent of the difference between 100 percent and a state’s calculated matching rate. For a state with a matching rate of 50 percent, the enhancement raises the matching rate to 65 percent. The enhancement benefits high-income states, since it is calculated from the 50 percent floor. New York, for example, receives about $1.86 for every dollar it spends instead of just the dollar-for-dollar match resulting from the 50 percent floor. Mississippi’s enhanced matching rate is 83 percent, so they receive $4.88 for every dollar they spend. However, the formula doesn’t benefit Mississippi more than New York.

The formula’s ability to narrow the disparities between states depends on how much each state spends. In 2004, New York spent twice as much per capita on Medicaid as did Mississippi ($2,165 per capita compared to $1,180 per capita, respectively). Even though New York’s matching rate per dollar is lower, they receive more federal Medicaid dollars ($23.4 billion compared to Mississippi’s $2.7 billion) because they spend more. Indeed, the Government Accountability Office reports that while the federal matching rate moves 30 states toward the national average (including Mississippi), it also moves about 21 states away from the national average (including New York).28

How Much Is Lost to Fraud and Abuse? Fraud and abuse have plagued Medicaid since its inception. In 1997, the General Accounting Office estimated that fraud and abuse may be as high as 10 percent of Medicaid spending.29 For example, a 1993 investigative report of the Illinois Medicaid system by the Chicago Tribune found:30

- In one year, 71,064 Medicaid patients visited a doctor’s office more than 11 times (compared to a national average of six visits per year), while four patients made more than 300 visits in one year.

- In one day, one patient saw five doctors, visited a pharmacy seven times and had 22 prescriptions filled with 663 pills.

The Tribune also uncovered “Medicaid mills,” that freely prescribed drugs, syringes and other medical products that were sold by patients on the street.

More recently, a year-long investigation of New York Medicaid by the New York Times found massive provider fraud. For example:31

- Dr. Rosen, a dentist in New York’s Medicaid program, claimed to have performed nearly 1,000 procedures in a single day.

- In September alone she claimed to have performed 9,500 procedures.

- All told, she and a colleague billed New York Medicaid $5.4 million in 2003.

Most fraud is committed by physicians and other providers, rather than patients, but providers often turn a blind eye to unscrupulous patients abusing or defrauding the system. For instance, the Times reports that a Brooklyn doctor prescribed more than $11 million worth of a synthetic growth hormone used to treat AIDS patients over a three year period. Investigators say these patients were part of an elaborate scheme to obtain a drug popular with bodybuilders buying on the black market. New York Medicaid’s yearly cost for this growth hormone grew from $7 million to $50 million within a year of the scheme becoming prevalent.

Another source of fraud and abuse is the federal Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program. Many people with disabilities access Medicaid benefits by qualifying for SSI. Since coverage is often related to medical conditions that are fairly easy to fabricate or exaggerate, individuals and parents have incentives to misrepresent their medical conditions. According to the Government Accountability Office (GAO), “middlemen” who provide translation services to beneficiaries who do not speak English, coach them on feigning and exaggerating mental disabilities in order to receive SSI benefits; middlemen also work with dishonest health care providers to supply faulty medical information. Additionally, a number of SSI recipients have admitted to transferring ownership of assets in order to quality for SSI benefits.

- Between 1990 and 1994, an estimated $74 million in assets were transferred, including cars, cash, houses and land.

- Between 1996 and 1997, the Inspector General’s Office received 12,680 complaints of SSI fraud, constituting about 37 percent of all fraud allegations received from the public.

Unlike the poor and near poor, whose income and assets can be documented, these recipients can “game” the system to obtain coverage.32

[page]Medicaid was intended to improve access to medical care and thereby the health of the indigent. Arguably, it has done neither. And as the program has expanded to cover additional populations, including the near poor and even middle class individuals, the evidence suggests that it is displacing, or crowding out, private health insurance coverage.

Impact on Access to Care. It is commonly assumed that Medicaid enrollees have greater access to health care than if they were uninsured. But there is little evidence that is true. Most enrollees rely on the same public and not-for-profit hospitals and clinics that have always provided a health care safety net for the poor.33 Medicaid is the primary social safety net for indigent health care — but not the only one. For example, community health clinics and hospital emergency rooms are often providers of last resort. The existence of this free care (charity care) often makes people eligible for Medicaid feel that enrollment is unnecessary. Free care, in other words, appears to be a substitute for Medicaid.

“Medicaid spending substitutes for free care by doctors and hospitals.”

In fact, where Medicaid spending is low, spending on free care is high — and vice versa. For example, an NCPA analysis of health regions in Texas found that the area with the highest average Medicaid cost per enrollee spent more than twice as much as the area with the lowest average cost.34 But we found that adding spending on free care to Medicaid spending cuts the variation in regional health care spending in half. In other words, free care substitutes for Medicaid spending, as regions that spend less on Medicaid tend to spend more on free care and vice versa. [See sidebar on “Free Care.”]

Impact on Health. An oft-cited argument for Medicaid is that making health care virtually free at the point of consumption encourages preventive care and improves health outcomes. This could potentially reduce overall health care costs. Unfortunately, there is little evidence that this occurs. Studies suggest explicit attempts to encourage the use of preventive care by Medicaid beneficiaries are generally unsuccessful. For example, one study found that outreach programs in North Carolina had a very small impact on utilization.35 Another study found that receiving Medicaid benefits for a year increased the probability children would receive checkups by only 17 percent. The researchers concluded that “factors other than insurance and income, such as the low educational attainment of low-income mothers, explain approximately 80 percent of the gap between low-income and other children in their well-child visits.”36 Additionally, there is no evidence that becoming eligible for Medicaid significantly improves child immunization rates.37

However, analyzing the use of Medicaid services tells us only about inputs, not outcomes such as health improvement. The evidence of Medicaid’s effect on health is conflicting. For example, Medicaid eligibility is somewhat associated with a lower risk of infant mortality.38 And University of Washington researchers found some evidence that Medicaid decreases low-weight births for medically high-risk women.39 Studies in other states, however, have found Medicaid expansion had little effect on prenatal care and outcomes.40

“Medicaid creates disincentives to work and save.”

Impact on Income and Wealth. Like other means-tested government benefits, Medicaid creates disincentives to work and save.41 Income tests discourage work by withdrawing benefits as income rises. Asset tests encourage people to transfer or spend down their assets or avoid saving to become or remain eligible. Knowing their medical needs will be covered by Medicaid, eligible families may boost consumption and save less for emergencies. University of Kentucky economist Aaron Yelowitz and Jonathan Gruber of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology found that Medicaid recipients consumed more and saved less, reducing their average household wealth in 1993 by $1,600 to $2,000 (in today’s dollars).42

Impact on Private Insurance. Many assume Medicaid insures people who otherwise would not have access to private insurance.43 However, Medicaid also induces some people to drop their private coverage in order to take advantage of free health insurance offered by the state. Often this occurs when employers cease offering insurance coverage as large numbers of current and prospective employees become eligible for Medicaid. As a result of such crowding out, the cost of expanding public insurance programs has been high relative to the gain. For example, if for each new enrollee in a public program at least one person loses private insurance, there will be no net reduction in the number of uninsured, despite the higher taxpayer burden. If for every two new enrollees in the public program one person loses private insurance, the cost to the taxpayers for each newly insured person will double.44

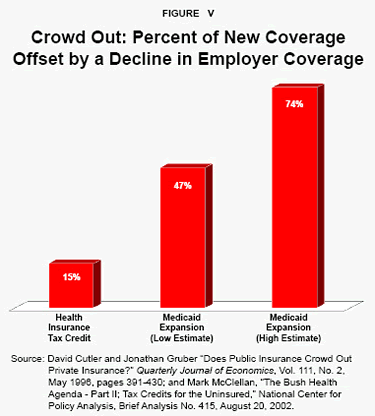

David Cutler of Harvard University and Jonathan Gruber of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology found that Medicaid expansions in the early 1990s were substantially offset by reductions in private coverage.45 They found that for every additional dollar spent on Medicaid, private sector health care spending was reduced 50 to 75 cents on the average.46 Thus taxpayers incurred a considerable financial burden, but at least half, and perhaps as much as three-fourths, of the expenditures replaced spending by individuals, rather than buying additional medical services. [See Figure V.]

“Medicaid crowds out private insurance coverage.”

In 1997 Congress expanded access to public health insurance with the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP). This program provides additional federal matching funds to states to cover children in families whose incomes are too high to qualify for traditional Medicaid. SCHIP also crowds out private coverage. Take a low-income working family covered by an employer-sponsored health plan. The employer might have covered some or all of the cost of insurance premiums for the employee and family with pretax dollars. But paying wages is more attractive to actual and potential employees if coverage is provided by the state. Thus SCHIP offered some employees the opportunity to increase wages and reduce their out-of-pocket health care costs.

“Increased Medicaid enrollment was offset by a drop in private insurance coverage.”

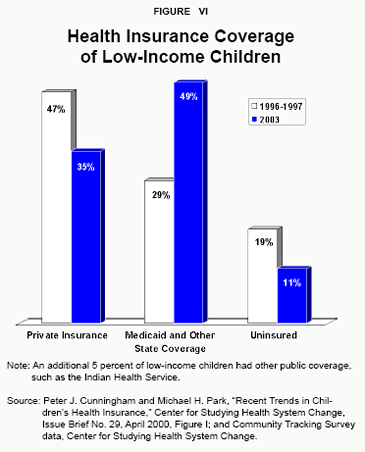

As a result of expansions of Medicaid and SCHIP, the number of poor children without health insurance fell from 19 percent in 1997 to 11 percent in 2003. During this period enrollment of low-income children in public programs increased from 29 percent to 49 percent.47 Meanwhile, the percentage of children from low-income families covered by private insurance fell from 47 percent to 35 percent, although there was little change in the percentage of privately insured children in households at higher income levels. [See Figure VI.] Thus, SCHIP apparently induced low-income employees to drop their children from company-sponsored health plans.48 The crowd-out of private insurance due to the expansion of public programs was 0.6, meaning that every percentage point increase in public coverage resulted in a reduction of about 0.6 percentage points in private coverage among low-income children.49

“Medicaid expansion has not reduced the ranks of the uninsured.”

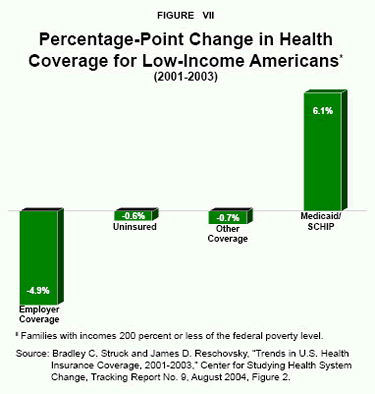

More recently, from 2001 to 2003, the proportion of low-income Americans enrolled in public programs rose 6.1 percentage points. However, this increase was offset by a 4.9 percentage point decline in coverage by employer-sponsored plans. Overall, the rate of uninsured fell only about one-half point.50 [See Figure VII.] Casual empiricism suggests that it takes a 13 percentage point increase in public coverage to reduce the uninsured rate by 1 percentage point.

[page]

New York has less than 7 percent of the U.S. population, but spends about 14 percent of the nation’s Medicaid dollars.51 The average New Yorker spends more on Medicaid (through taxes) than the average citizen of any other state. The state also spends more on each Medicaid enrollee than almost any other state. Including federal, state and local spending, in 2004, the latest year for which complete data is available:52

- New York spent $10,349 per Medicaid enrollee, compared to the nationwide average annual cost of about $6,834. [See Figure VIII.] Only New Hampshire spent more.

- New York Medicaid spent about $2,165 for every man, woman and child living in state — more than any other state and almost two-and-one-half times the national average of $873.

“New York spends more per Medicaid enrollee than almost any other state.”

Why Does New York Spend So Much More Than Other States? Some might assume that Medicaid costs are higher in New York because the cost of living is higher than in other states, especially in New York City. However, we compared New York City to Columbus, Ohio, where the local cost of living is at the average for the nation as a whole. The findings:53

- In fiscal year 2003-2004, Medicaid spending in New York City averaged $9,842 per enrollee, almost twice as much as the $5,082 spent in Franklin County (Columbus).

- Adjusted for the cost of living in each area, New York City spending per enrollee was still twice as high as in Columbus, Ohio.

Thus higher living costs do not account for the relatively high Medicaid spending in New York.

New York spends more because of policies that encourage higher spending and discourage cost control. Other states share some of these same problems, but none have such a wide array of perverse incentives. Specifically:

- Unlike most other states, New York offers coverage to virtually all optional populations and covers virtually all optional services.

- New York underpays physicians and overpays hospitals, even though physician therapies are often more cost effective than hospital therapies.

- New York does not use smart buying techniques, such as selective contracting, to reduce costs.

- Compared to other states, New York pays premium prices for drugs and imposes few restrictions on doctors who prescribe the most expensive drugs, when lower-cost alternatives are often just as effective.

- The political incentives to spend are greater since the New York legislature bears only a fraction of the cost (less than almost any other state) of the benefits it confers; a substantial share of the cost is borne by county property-taxpayers in addition to federal taxpayers.

- New York does not aggressively pursue fraud — even failing to spend a substantial portion of the federal funding available for antifraud efforts.

- New York’s insurance regulations raise the cost of private insurance, and make (free) Medicaid coverage more attractive.

Let’s look at how each of these features of the system raises costs.

Costly Policy: Offering More Benefits to More People. One reason New York Medicaid is so costly is that the state covers virtually all optional populations and provides virtually all optional benefits.54 Medicaid covers an estimated 4 million New Yorkers,55 or one in every five residents. New York has a higher proportion of residents in Medicaid than most states — about 50 percent more than the national average (21 percent versus 14.3 percent).56

There are 35 optional Medicaid services for which the federal government will provide matching funds. New York provides 31 of these services. These include, for instance, podiatry, which is only funded in 26 other states. Only 17 other states fund “personal care” and only 15 others offer private duty nursing.57 [For a list of optional benefits, see Appendix Table IIa-c.]

“New York covers virtually all optional populations and benefits.”

Following is a detailed discussion of three of these optional benefits that are widely utilized in New York: long-term or nursing home care, home care and personal care, and transportation services. Long-term care is an optional benefit every state provides, but the New York program is unusually costly. In other states, home and personal care substitute for more expensive institutional care, but all three types of benefits are utilized in New York to a greater extent than other states. Finally, New York provides the most extensive, and expensive, transportation services of any state.

Optional Benefit: Long-Term Care. Among the optional benefits New York provides is long-term care. Although every state provides some nursing home benefits, New York spends more than the average state on institutional long-term care.

- About 17 percent of the Medicaid money spent on long-term care in the United States is spent in New York.58

- Nationally, Medicaid pays for two-thirds of nursing home care; in New York it pays for more than three-fourths of nursing home care (78 percent).59

What accounts for the higher spending on long-term care? One reason is that New York Medicaid has a higher proportion of blind, aged and disabled beneficiaries than the U.S. average — accounting for nearly one-third (32 percent) of its enrollees compared to the national average of 24 percent.60 Adding to this is the higher labor and long-term care costs in New York City. A comprehensive study of all the states by the federal government found that nursing homes in New York state were about 46 percent more expensive than the national average, and even after adjusting for differences in the cost of living are approximately 29 percent higher than the national average.61 Another study of metropolitan areas found nursing home costs in New York City were more than double that of other major cities.62

“One-fourth of all Medicaid personal care dollars are spent in New York.”

Optional Benefit: Personal and Home Care. Another widely utilized benefit is personal care and home care. Personal care, sometimes referred to as “custodial care,” generally involves assistance with activities related to daily living (bathing, toilet assistance, eating and housekeeping). Home care can also include assistance with daily living activities, but also includes skilled nursing.63 Some 13 percent of New York Medicaid enrollees utilize personal care and 8 percent use home care, compared to a nationwide average of 11 percent and 2 percent, respectively.64 And, according to the Citizens Budget Commission — a taxpayer watchdog group — New York provides much more home care than any other state:65

- Whereas those receiving home care benefits in other states get helpers an average of 11 hours per week, the average is 30 hours per week in New York.

- Average spending on personal care per capita is $18.11 across the country, but New York spends $91.21, more than four times as much.

- Overall, fully a fourth of all Medicaid dollars spent on personal care nationwide are spent in New York!

Home health aides typically come once a day to wash dishes, perform light cleaning, deliver or prepare meals, and help with bathing and dressing. Enrollees often begin receiving personal care after discharge from a hospital, when a Medicaid official assesses their level of disability and calculates the number of hours of assistance they need for daily living activities.

Once recuperated, most recipients have come to expect the higher level of service they were receiving (due to illness) and resist having the number of hours of personal care assistance cut back. If clients complain, the system generally favors clients over administrators. In New York, Medicaid enrollees often use home care attendants for nonmedical tasks such as shopping. Furthermore, in some cases, assistants are chosen by the recipients themselves, and can include other members of the household, relatives or neighbors. Thus, Medicaid often pays family members to do what they would have done anyway.

Home- and personal-care services may be justified when they allow the disabled or frail seniors to avoid institutional care, but many New Yorkers receiving home care could perform more of the tasks themselves and are receiving more assistance than is needed to keep them out of institutionalized care. Thus, apart from skilled nursing services, home care often amounts to free maid service.

Optional Benefit: Transportation. New York also provides such nonmedical services as transportation. For example, New York Medicaid pays for wheelchair-accessible vans (called ambulettes) to transport Medicaid enrollees with mobility problems to and from medical treatments. The service is intended to provide transportation only to those who use wheelchairs or who cannot walk without assistance. But most of those taking ambulette rides have no mobility problems and, for them, the service is actually a free taxi service. In 2005, the New York Times reported:66

- Two doctors each ordered more than 90 trips per day for patients.

- At another clinic, one patient used the service 153 times in a single year while another patient used the service 152 times — about one ride every two-and-one-half days.

- Other patients used the service more than 130 times.

“New York pays $60 to transport patients who could ride a bus for $2.”

For patients who qualify for the service, cheaper alternatives exist. A typical bus ride in New York City costs $2 and a taxi ride costs $10, according to the New York Times. But Medicaid typically pays contractors $25 or $31 each way to transport patients to their appointments in an ambulette. Overall, New York Medicaid spent $316 million to transport patients to doctors’ offices and hospitals in 2003. This works out to 10.5 million to 12.5 million rides per year.67

Costly Policy: Underpaying Physicians and Overpaying Hospitals. Routine examinations and treatments — including minor surgical procedures — can be provided more efficiently in a doctor’s office than a hospital. But many doctors who could provide such services do not do so. They do not participate in Medicaid because reimbursement is so low. As a result, the patients turn to much costlier settings, such as hospital clinics and emergency rooms.

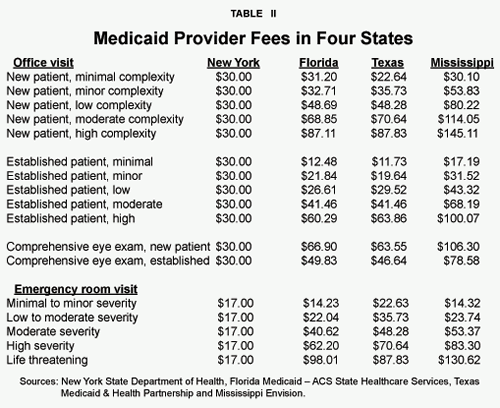

The Effects of Underpaying Physicians. Medicaid reimbursement rates for physicians are typically lower than what physicians receive from the private sector in every state. But in New York the discrepancy is even greater. In fact, New York has some of the lowest physician payment rates found anywhere in the country. For instance:68

- New York doctor receives $30 for a visit by an established patient requiring a highly complex exam, whereas Mississippi pays a physician about $100 for the same exam. [See Table II.]

- An eye doctor in New York receives $30 for a comprehensive examination of a new patient, whereas Texas and Florida pay more than twice as much for the same service.

“New York underpays physicians.”

Another way to think about Medicaid physician payments is to compare them to what Medicare pays:

- Medicare pays physicians only 83 percent as much as private insurers, on the average, nationwide.69

- Medicaid fees for physician services are 69 percent of what Medicare pays, nationwide, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics,70 and perhaps as little as 62 percent, according to an Urban Institute estimate.71

- By contrast, in New York, Medicaid pays physicians only about 45 percent of what Medicare pays.72

Only two state Medicaid programs — in New Jersey and Rhode Island — pay physicians so little compared to Medicare. In New York City, for instance, Medicaid will only pay a specialist $30 for a consultation of moderate complexity, while Medicare pays $200.73 Medicaid physician payments also vary by type of service. For example:74

- New York Medicaid pays 65 percent of what Medicare pays obstetricians.

- It pays primary care providers only 40 percent of what Medicare pays.

- Other specialists are only paid about 31 percent of what Medicare pays.

“Hospital care substitutes for physician visits.”

These reimbursement rates affect access to care. Laurence C. Baker and Anne Beeson Royalty found that a 10 percent increase in Medicaid fees raised the number of poor patients visiting office-based (private) physicians by 3.4 percent, and correspondingly reduced the number visiting public physicians (such as in public health clinics) by 3 percent. 75 When physicians are rewarded for taking complex cases, they have an incentive to accept them. When fees are not adjusted for the complexity of the case, they have an incentive to avoid complex cases.

“New York spends nearly three times as much as the average state on hospital care.”

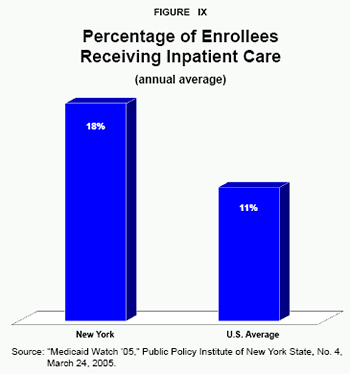

The Effects of Overpaying Hospitals. When access to private physicians is limited, patients rely more on inpatient treatment. In New York state, 18 percent of Medicaid patients receive inpatient care compared to just 11 percent nationally.76 [See Figure IX.] Furthermore, in contrast to its treatment of physicians, New York pays hospitals generously. When New York deregulated the hospital industry in 1997, the system of Medicaid fee-for-service was left largely intact, allowing Medicaid enrollees to go to any hospital, regardless of its efficiency. Consequently, Medicaid began to pay the highest fees of any payers — including private insurers.77 In most states Medicaid pays the lowest fees of any payer.

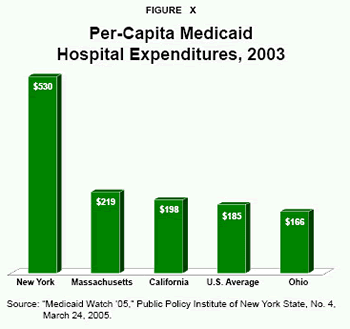

This generous payment policy does not give hospitals any incentive to increase productivity or reduce costs. As a result, in 2003, New York Medicaid paid about $10 billion to hospitals for inpatient care, subsidies for graduate medical education and hospital-based clinics — more than any other state Medicaid program. Furthermore:

- New York spends nearly three times as much per state resident on inpatient care ($530) as the national average ($185).78 [See Figure X.]

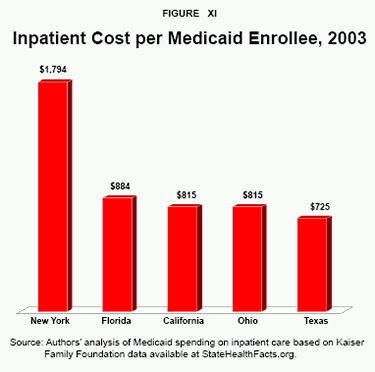

- The inpatient cost per Medicaid enrollee in New York is also greater than in other large states — $1,794 in 2003, compared to $725 in Texas, $815 in California and Ohio, and $884 in Florida.79 [See Figure XI.]

For instance, some New York hospitals have high fixed operating costs — due to a large number of empty beds. (Empty patient rooms generate no revenue, but incur costs — such as heating and cooling.) In fact, New York has 21 percent more hospital beds per capita than the national average. Statewide, about 9,100 hospital beds were eliminated from 1990 to 2005, but experts suggest that closing another 20,000 beds would make the system more efficient while meeting the demand for beds.80 New York has somewhat reduced excess capacity, but instead of closing the most inefficient and underutilized hospitals, it has closed a few beds at a number of hospitals.81

“New York spending per patient is higher than in other large states.”

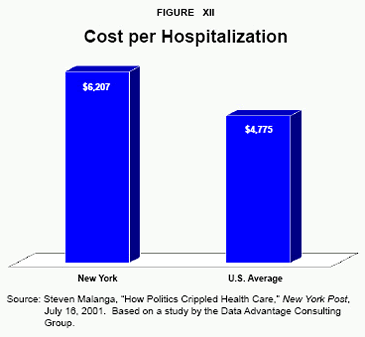

Furthermore, average administrative costs in New York hospitals are more than 13 percent higher than the national average and the cost of patient care is nearly 10 percent higher — after controlling for case severity and higher regional labor costs.82 For similar cases, Medicaid-paid hospital stays in New York cost about 30 percent more than the national average.83 [See Figure XII.] And patients spend 37 percent longer in the hospital, on the average, than patients with similar conditions in other states.84

“New York spends 30 percent more than average on similar cases.”

Costly Policy: Ineffective Managed Care. Managed care was introduced into Medicaid in order to increase access to care, and to provide services efficiently. In New York City, Medicaid managed care has done a poor job of pursuing both goals.85

Managed care organizations usually contract with area hospitals and doctors to provide services at negotiated discounts. However, most New York City Medicaid managed care plans are administered by large public hospitals, which are the primary providers of health services.86 These organizations do not have the same incentives to control costs as private sector insurers. For instance, a private sector insurer would seek to hold down the cost of caring for enrollees by contracting selectively with health care providers who were efficient at providing specific services. Yet a public charity hospital that has contracted to care for the same group has the incentive to perform all medical services in-house even if its facilities are not as efficient at providing some medical services as other hospitals. Even if the hospital is inefficient and losing money, keeping all medical services in-house minimizes loses. Whereas a nonprofit or for-profit health plan would go out of business, a charity hospital often uses political clout to increase subsidies.

Furthermore, most New York City public charity hospitals lack large networks of participating physicians and have to rely on outpatient clinics affiliated with the hospital.87 As a result, access to physicians is less convenient and many enrollees cannot see the same doctor each time they schedule an office visit. This reduced access to primary care physicians often leads to over-use of emergency departments in situations when a physician office visit would have been less costly.

Most states, including New York, have enrolled a significant proportion of their Medicaid beneficiaries in managed care plans. However, like most states, New York exempts substantial patient populations from its mandatory managed care enrollment: the elderly and disabled. Seventy percent of Medicaid costs in New York are for the elderly and disabled. The average yearly cost per person to care for them is 10 times higher than for nondisabled children and five times the cost of caring for the parents of nondisabled children. Exempting the most intensive users of Medicaid services from cost-control efforts is an expensive missed opportunity. These patient groups have problems accessing care, and could benefit from the continuum of care and case management that managed care networks can offer. For many of them, managed care is not even available on a voluntary basis.

Uniquely, New York applied for and received a special waiver to allow managed care plans, community groups and clinics to recruit new enrollees and help them fill out the enrollment forms. This process, known as “facilitated enrollment,” makes it easier to sign up ineligible people and gives HMOs the ability to steer enrollees to their own firms.88 It also allows managed care contractors to sign up less costly patients and avoid more costly ones.

An alternative to managed care is to allow patients to manage their own health care dollars and shop for care as empowered consumers in the medical marketplace. We will consider this option below.

“New York spends more on drugs than any other state.”

Costly Policy: Paying Premium Prices for Drugs. New York spends more on drugs than any other state — about $3.413 billion in 2002.89 It also pays higher average prices for drugs than any other state except New Jersey.90 And it spends more on drugs per enrollee than any of the other 10 most populous states, at about $957 per enrollee.91

Why? One reason is that the New York state program provides few incentives for enrollees to economize on drug costs, despite evidence that there is wide variation in prices for the same drug as well as less expensive generic and therapeutic alternatives for many drugs.92 Furthermore, according to a 2004 Inspector General’s report, New York consistently paid some of the highest prices of any state for Medicaid drugs.93 For instance:

- New York pays $3.67 per dose for the acid reflux drug Omeprazole even though an identical drug, Prilosec, is available over-the-counter for about 75 cents per dose.94

- New York paid $18.70 per container of the asthma drug albuterol while Texas Medicaid only pays $6.63.

Another reason for New York ‘s high drug costs is that the state does little to restrict the drugs for which it will pay. Many private health plans have some type of preferred drug list with increased cost sharing for drugs that have significantly cheaper alternatives. Most state Medicaid programs have a drug formulary, which is a list of prescription drugs for which the program will pay. The drugs are selected through a competitive bidding process, and drug companies usually agree to reimbursement rates that are steeply discounted from the retail price. Many states will only include one drug from a class in the formulary. Another way to save money is negotiating discounts with drug manufacturers.95 New York has taken steps to reduce drug spending, but their efforts have lagged behind other states and have so far been ineffective. It recently began encouraging the use of generic drugs, but doctors can easily substitute higher-priced brand drugs.96

“The State of New York pays $1 for every $4 in benefi ts it confers.”

As with other types of managed care there is a danger that drug formularies can become bureaucratic obstacles that prevent patients from getting the drugs they need. Also, administrators may be tempted to sacrifice quality care in order to reduce costs. Ideal drug policy minimizes costs without harming patient welfare. Poor drug policy harms patients and may (because of adverse health effects) not even reduce costs.97 Frank Lichtenberg of Columbia University has found that newer, more expensive drugs may offer more effective treatment and reduce total health care costs. Lichtenberg found that lowering the average age of drugs used by roughly a decade (that is, from 15 years to 5.5 years) results in an increase of $18 in drug spending but a net reduction in total health care spending by $111. Most of the net reduction was due to decreased hospitalizations and fewer office visits. 98

“Counties have cut services and raised taxes to pay for Medicaid.”

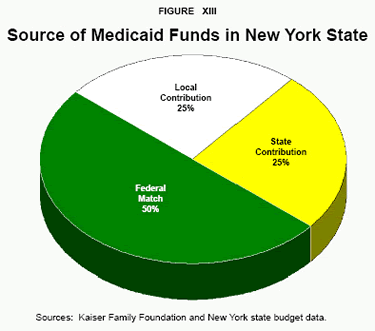

Costly Policy: Shifting the Cost of State Mandated Benefits onto Local Governments. One reason for the higher cost of New York Medicaid is the unusual way in which the program is financed. Unlike other states, New York requires its counties to pay a substantial portion of Medicaid costs.99 Figure XIII shows the break-down of New York Medicaid funding. Counties bear about 17 percent of the total cost of Medicaid. New York City’s local contribution is another 8 percent of the total. The federal government pays half the cost. Thus the State of New York pays only one-quarter of the cost of Medicaid.

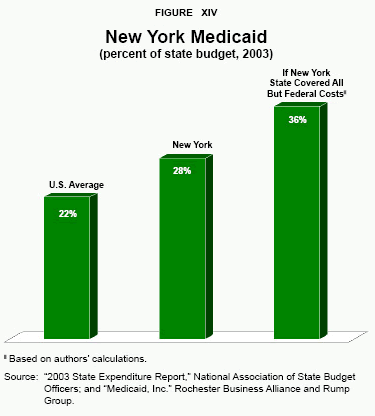

For every dollar the state spends, it can confer $4 of benefits. Politicians, therefore, are tempted to continue to confer benefits paid for by someone else. This means the state has much less incentive to economize.100 As a result, New York State spends about 28 percent of its budget on Medicaid — plus the counties’ spending — compared to about 22 percent of state budgets nationally.101 [See Figure XIV.]

According to the New York Times , many counties raised taxes more than 40 percent from 2003 to 2005. For instance, taxes in Albany County increased by about 70 percent over the past few years — largely to pay its share of Medicaid costs.102 To pay their Medicaid bills, some New York counties have cut other services:103

- Sparsely populated Chemung County closed a library two years ago.

- Chautauqua County cut back on bus routes and sheriff’s deputies.

- Oswego County reduced its work force by 16 percent and sold its nursing home.

- In 2005 Niagara County cut 96 staff positions.

Since property taxes are the main source of county revenue, Medicaid has caused substantial property tax increases. 104 According to the Public Policy Institute of New York, taxpayers living in upstate New York pay nearly $1 billion a year in additional taxes compared to an average state due to Medicaid.105 This has negatively affected the state’s economy.106 County leaders complain the tax rate is slowing business development. A 2004 Moody’s Investors Service report claims that counties in New York are facing financial trouble because of increasing costs, including employee wages and benefits, and the counties’ share of Medicaid.107

Costly Policy: Ignoring Fraud. As noted above, 10 percent of Medicaid spending nationwide may be lost to fraud.108 In New York, a former State Inspector General estimates that waste and unnecessary services that don’t rise to the level of criminality may add another 20 to 30 percentage points to this amount.109

“New York Medicaid spending equals more than one-third of the state budget.”

The New York Times found massive fraud merely by analyzing data obtained through the Freedom of Information Act. The state has failed to try reforms that other states have used successfully. It has also failed to pursue cases when fraud is found.110 A 2000 press release from the Office of the New York State Attorney General illustrates the size of the problem. On the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the New York Medicaid antifraud unit, Attorney General Eliot Spitzer’s office announced a total of $326 million in fines, overpayments and restitution had been recouped since the unit’s inception 25 years earlier.111 Yet the amount they recovered in two-and-a-half decades was equivalent to only about 7 percent of the estimated cost of fraud that occurred in 2005. In the past 15 to 20 years, the number of people dedicated to fighting Medicaid fraud in New York has fallen by about 70 percent. Interestingly, the amount of money recovered by the antifraud team has fallen by about that same percentage since 2000.112 In 2004, New York Medicaid paid about 400 million claims, but only 37 cases of suspected fraud were uncovered.113

Other states are far more aggressive in rooting out fraud. In recent years California added about 400 people to its antifraud staff. The Medicaid budgets in Ohio and Illinois are only about one-quarter of the budget in New York, but they audit three times as many providers each year.1140 The federal government is willing to pay 75 percent of the cost of beefed-up state antifraud efforts, but New York does not spend enough to receive the full federal match.

“New York uncovered only 37 cases of fraud in 2004.”

Until recently, New York counties were not allowed to police the Medicaid providers within their areas, even though they pay a significant portion of the costs. They could not investigate doctors and providers who where bilking the program with questionable billings, and were not even allowed to find out what local providers were billing Medicaid for services.115 The state alone had the power to investigate fraud. Unfortunately, the state has done a dismal job.116

In the fall of 2005, the New York State Department of Health finally allowed 12 counties to look for unusual patterns in billings from Medicaid providers that might indicate fraud.117 After examining just a small portion of the program, investigators in Rockland County discovered what appeared to be $13 million in questionable charges over a period of less than two years.118 Even when patterns of fraud are found, local officials are not allowed to prosecute, sue or even suspend the providers. Only the state Department of Health has that authority.119

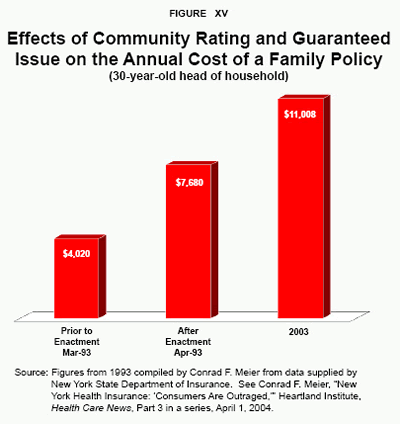

Costly Policy: Crowding Out Private Insurance . As noted, Medicaid crowds out private insurance coverage by offering a free alternative. New York exacerbated this effect by enacting two regulations in 1993 that raised the cost of private insurance : community rating and guaranteed issue . These laws allow people to obtain insurance once they become ill (guaranteed issue) and require insurers to charge the same price regardless of age and health status (community rating). As a result, young, healthier people are substantially overcharged for their insurance while older, sicker people generally pay less than their true cost of care. For instance:

- Just prior to enactment of these laws, a New York family of four headed by a 30-year-old could obtain coverage for about $4,000 per year.

- Immediately after enactment, that family’s cost rose to $7,680.

- After a decade of premium increases, health insurance now costs the same family about $11,000.120 [See Figure XV.]

Conversely, in 1993, a family headed by a 60-year-old paid $11,640 annually. Immediately after guaranteed issue and community rating were enacted this fell to $7,680 and 10 years later stood at about $11,008. So, in effect, the expected health care costs of the older, more-expensive-to-treat couple was shifted to the younger, healthier couple.

“Insurance regulations raise the cost of private coverage.”

Defenders of these laws claim that they protect consumers by guaranteeing access to coverage — especially for those who are ill and need care the most. But the only people who have an incentive to purchase coverage are those who are ill. After all, why pay premiums when you are healthy if you can always insure (at the same rate) after you get sick. But if only ill people join a health insurance pool, the cost per person will be enormously high. As more and more healthy people drop insurance and those remaining in the pool are sicker and more expensive to treat, premiums must be raised. This creates an incentive for the young and the healthy to drop their coverage or to avoid buying insurance in the first place. One study found that community rating and guaranteed issue in the small group market increased the likelihood of being uninsured by more than 28 percent.121

The Politics of Medicine. We have seen that Medicaid spending in New York is unusually high. But why do taxpayers and policymakers tolerate such high costs? New York City has an especially large number of medical schools, teaching hospitals and research centers. Higher Medicaid reimbursement rates for hospital services pay for these resources.122 New York labor unions are powerful, and hospital labor is well paid.123 In 2002, the New York State legislature increased Medicaid reimbursements for hospitals in order to raise the wages of certain health care workers.124 Although recruiting and retaining health care workers might sound like a worthy goal, the move was largely due to strong health care unions that primarily represent low-skilled workers.125 About 10 percent of New York’s nonagricultural workforce (800,000 people) is employed in health care, making providers politically powerful opponents of reform.126

Whenever fiscal restraint is suggested, reform opponents fight tooth and nail to derail the process. In 1999 the Service Employees International Union local 1199 and the Greater New York Hospital Association launched an expensive lobbying campaign warning of huge layoffs and closed hospitals.127 Again, in 2005, when Gov. Pataki announced plans to restrain Medicaid costs, the same union and the Greater New York Hospital Association ran advertisements using scare tactics to attack the plan.128

[page]If New York Medicaid were as efficient as the average state program, it could spend billions of dollars less to achieve the same health outcomes, and would have billions of dollars each year to fund tax cuts or other spending programs. Achieving average Medicaid efficiency is a modest goal. A more ambitious goal is to achieve the efficiency of the average private-sector health plan.

New York can improve Medicaid services, while controlling costs, by adopting common-sense reforms, including techniques commonly used in the private sector; by contracting with private sector providers for services; by fundamentally restructuring its program; by giving enrollees financial incentives to reduce unnecessary use of services; and by moving patients out of Medicaid and into private sector plans. As part of this reform effort, the state also needs a complete overhaul of long-term care and home health services.

Some of these reforms could be carried out by the state on its own, while others require what amounts to pro forma approval from the federal government. More aggressive reforms require specific federal waivers. [See the sidebar “Using Waivers to Implement Reforms.”] The most desirable reforms will require federal legislation.

Common-Sense Reforms

To reduce Medicaid costs, New York should begin by employing measures that are common in the private sector and that achieve results. The following are some examples.

“New York could contract with the most efficient providers for each service.”

Substituting Less-Expensive for More-Expensive Providers. Why pay more when the same quality of care is available for less? Private-sector health plans routinely contract selectively with providers, choosing to direct their enrollees to providers who charge less for the same level of quality. These plans typically require enrollees to use facilities and physicians that are “in network,” or to pay a larger share of the cost if they use providers that are “out of network.” Competition encourages potential contractors to discount services. It also improves quality by giving hospitals incentives to specialize in those services they do well.

Through specialization, hospitals can perform a large volume of procedures, or care for a large volume of patients with similar conditions, at a lower cost. Hospitals can reduce costs by eliminating inefficiencies, including unnecessary services, excessively long hospital stays, excessive compensation to noncritical staff, inefficient staffing levels, and so forth. Hospital executives will find innovative ways to cut costs when they have better incentives to do so. 129

Selective contracting can work for New York Medicaid. There are opportunities to negotiate discounts for most medical services. Other states are using competitive bidding and selective contracting for eyeglasses, medical equipment, transportation and other services. 130 For example, Medi-Cal , California ‘s Medicaid program, began selective contracting for hospital services in the early 1980s. Four years later the state was spending nearly 8 percent less than it would have without selective contracting.131 The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) found that contracting reduced per diem charges for hospital stays in California about 16 percent below what they otherwise would have been. The greatest savings were in areas with stiff competition among hospitals.132

“Selective contracting can reduce costs and improve quality.”

Although New York Medicaid managed care plans are free to negotiate with providers, we have seen that there is an unfortunate conflict of interest. Many Medicaid managed care plans in New York City are administered by charity hospitals that have an incentive to use their own facilities as much as possible.

Over the last 10 years, hospital pricing in New York State has been deregulated so that private insurers are free to negotiate hospital charges for both their managed care and fee-for-service plans.133 This allows an insurer or health plan to selectively contract with hospitals for particular services and steer patients to those facilities by requiring a patient or doctor to obtain a preauthorization from the health plan before admission. Unfortunately, New York Medicaid has not taken advantage of this for hospitals serving its fee-for-service patients.134 In New York, hospital reimbursement rates for Medicaid patients are set by the state and do not vary, regardless of the hospital used.

New York Gov. George Pataki has proposed allowing Medicaid to contract for high-cost, specialty hospital services for fee-for-service patients.135 Medicaid would award contracts to selected hospitals and negotiate payment rates for services provided by those hospitals. For example, Medicaid could selectively contract specific high-cost procedures to “Centers of Excellence,” hospitals that perform a high volume of particular procedures for which there is a demonstrated relationship between volume and quality. Hospitals that don’t receive contracts would not be reimbursed for providing such services unless they were preauthorized, or the patient was admitted due to an emergency. This is a modest reform that is long overdue.136

Substituting Less-Expensive for More-Expensive Therapies. Treatment in outpatient settings, such as doctors’ offices, is generally less expensive than treatment in a hospital. However, Medicaid patients have limited access to physicians other than in public health clinics or hospital emergency rooms. Paying higher fees to physicians could increase patients’ access to health care and reduce expensive emergency room visits. The key to improving patient access is to raise reimbursement rates for examinations, tests and procedures that can be performed in a doctor’s office.

Performing more procedures in outpatient settings that were once only performed in hospitals (such as minor surgeries that don’t require an over-night stay) is a common way of reducing costs.137 A Pennsylvania study found about 10 percent of all hospitalizations for patients under age 65 are potentially avoidable. Caring for these patients in lower-cost, more appropriate settings could have saved about $2.8 billion. In some cases procedures were performed in hospitals that could have been done in outpatient clinics. In other cases, inpatient care could have been avoided by timely physician care.138

Substituting Less-Expensive for More-Expensive Drugs. Managed care health plans use a variety of techniques to control drug costs, including preferred drug lists, formularies, negotiated prices with drug companies and single-source drug distributors. For example, many plans require enrollees to use a specific mail-order drug supplier to avoid a higher copay. Health plans frequently contract with a pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) to handle drug benefits. PBMs require enrollees to obtain a preauthorization to purchase brand name drugs that aren’t on their list of preferred or formulary drugs, or to use a non-network pharmacy.

Medicaid managed care plans generally also use PBMs to manage their drug benefits. However, some states have rules and regulations that limit the ability of PBMs to control drug costs. For instance, laws that prevent a PBM from requiring the substitution of generic drugs when they exist are used in some states.139 There are several bills pending in the New York legislature that would limit the ability of PBMs to require the use of mail-order pharmacies.140 New York also has a bill pending that would require PBMs to reimburse any pharmacy willing to meet the requirements of a drug plan.

“New York could use privatesector techniques to control drug costs.”

New York Medicaid should follow the example of other states and encourage the use of less-expensive drug alternatives, where quality is the same — including therapeutic, generic and over-the-counter substitutes. In the past few years, a number of prescription drugs have been moved over the counter, and are available at a much lower cost and without the hassle of obtaining a prescription. For example, take Claritin, a drug used by allergy suffers that was formerly available only by prescription. When it became available over the counter, the price fell substantially. The current prescription version of the drug, called Clarinex, is chemically similar.141 Yet a year’s supply of Clarinex costs about $949, compared to only $280 for Claritin and less than $15 for an OTC generic equivalent.142 Another example is the prescription version of the heartburn medication Prilosec, which cost $122.99 for 30 capsules at Walgreens.com, a daily cost of about $4.10.143 Currently, Walgreens.com sells a box of over-the-counter Prilosec with 42 capsules for $25.99, or a daily cost of 62 cents.144

The drug company Glaxo recently asked the Food and Drug Administration for the right to sell the obesity drug Xenical (Orlistat) over the counter. This might be an effective medication for overweight Medicaid patients. Glaxo expects the over-the-counter version to cost about two-thirds less than the prescription price.145 However, doctors will continue to prescribe the prescription version because it will cost Medicaid patients less out of pocket, even if they are charged a small copay (usually $3).

Unfortunately, Medicaid (and Medicare) will not pay for over-the-counter drugs, even if they can be substituted for more-expensive prescription drug therapies. Furthermore, there is a danger that drug formularies will become bureaucratic obstacles to needed therapies. One way to resolve these problems is to allow Medicaid patients to control some of the funds for their own health care. New York should consider allowing patients, rather than bureaucrats, to make these choices.

“Patient satisfaction with Cash and Counseling programs is almost 100 percent!”

Arranging Cash Accounts for Patients with Disabilities. A number of states have received waivers that allow them set up cash accounts which disabled Medicaid recipients can use to manage their own health care dollars and have direct control over the purchase of needed services.146 These programs, called “Cash and Counseling,” use a defined contribution approach.147 The patient is given a set dollar contribution and is free to choose his or her providers. The programs also involve counseling to assure that the patient is well-informed. Under traditional Medicaid, the states select the providers without patient input. Under this program, the patient can now choose his or her own provider. Surveys of participants in the program show that they have a higher quality of life with fewer unmet health needs.148 Remarkably, patient satisfaction is almost 100 percent.149

Reducing Errors in Diagnosis and Care. Eliminating errors in diagnosis can lead to better treatment at lower cost.150 Some of the most dangerous and costly problems in our health system include drug misuse, antibiotic overuse, preventable hospital-acquired infections, and the under-diagnosis and mistreatment of chronic conditions.151 The Institute of Medicine found that between 44,000 and 98,000 people die each year from preventable medical errors.152 A recent report found that nearly 100,000 people may die annually of hospital-inquired infections alone.153

Hospital-acquired infections are the fourth largest killer in America. Even more frightening, a new and deadly infection known as MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus auerus ) does not respond to commonly used antibiotics. In 2003, 57 percent of staph infections were a result of MRSA, and the percentage is rising. Additionally, hospital infections add $30 billion annually to the cost of health care. MRSA is commonly spread from patient to patient by doctors and hospital personnel and could be prevented by simple hygiene measures like washing hands before entering each patient’s room and changing outer garments between tasks. The problem is getting hospitals to enforce such measures. Some hospitals are taking aggressive steps, and both state and federal policies are changing to reduce this spreading epidemic:

- Some hospitals such as the University of Pittsburgh system are imposing stiff penalties, including termination and suspension of practice privileges, for staff and doctors who fail to wash their hands.

- Some states have passed laws that publicize a hospital’s “infection report card,” allowing patients to compare hospital infection rates before considering surgery; ideally, hospitals would compete for patients through reducing infection rates.

- Currently, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention collect data on hospital infection rates, but it is kept secret; this information should be made available to the public.154