Global competition is emerging in the health care industry. Wealthy patients from developing countries have long traveled to developed countries for high quality medical care. Now, a growing number of less-affluent patients from developed countries are traveling to regions once characterized as “third world.” These patients are seeking high quality medical care at affordable prices. Reports on the number of patients traveling abroad for health care are scattered, but all tell the same story. An estimated 500,000 Americans traveled abroad for treatment in 2005. A majority traveled to Mexico and other Latin American countries; but Americans were also among the estimated 250,000 foreign patients who sought care in Singapore, the 500,000 in India and as many as 1 million in Thailand. The cost savings for patients seeking medical care abroad can be significant. For example:

- Apollo Hospital in New Delhi, India, charges $4,000 for cardiac surgery, compared to about $30,000 in the United States.

- Hospitals in Argentina, Singapore or Thailand charge $8,000 to $12,000 for a partial hip replacement — one-half the price charged in Europe or the United States.

- Hospitals in Singapore charge $18,000 and hospitals in India charge only $12,000 for a knee replacement that runs $30,000 in the United States.

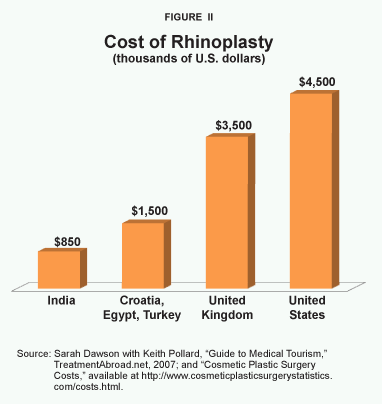

- A rhinoplasty (nose reconstruction) procedure that costs only $850 in India would cost $4,500 in the United States.

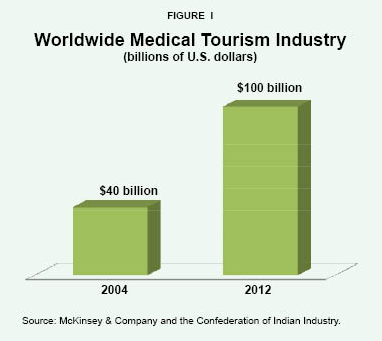

In 2006, the medical tourism industry grossed about $60 billion worldwide. McKinsey & Company estimates this total will rise to $100 billion by 2012.

Patients who are not familiar with specific medical facilities abroad can coordinate their treatment through medical travel intermediaries. These services work like specialized travel agents. They investigate health care providers to ensure quality and screen customers to assess those who are physically well enough to travel. They often have doctors and nurses on staff to assess the medical efficacy of procedures and help patients select physicians and hospitals.

Prices for treatment are lower in foreign hospitals for a number of reasons. Labor costs are lower, third parties (insurance and government) are less involved or not at all involved, package pricing with price transparency is normal, there are fewer attempts to shift the cost of charity care to paying patients, there are fewer regulations limiting collaborative arrangements between health care facilities and physicians, and malpractice litigation costs are lower.

How can patients ensure the medical treatment they will receive will be of high quality?

- Foreign health care providers often have physicians with internationally respected credentials, many of them with training in the United States, Australia, Canada or Europe.

- More than 120 hospitals abroad are accredited by the Joint Commission International (JCI), an arm of the organization that accredits American hospitals participating in Medicare; another 20 are accredited through the International Standards Organization; and some countries are adopting their own accrediting standards.

- Some foreign hospitals are owned, managed or affiliated with prestigious American universities or health care systems such as the Cleveland Clinic and Johns Hopkins International.

- Several companies are building and operating hospitals in Mexico that meet American standards, largely for American (and wealthy Mexican) patients.

- Finally, patients can also use online communities to get information on the safety and quality of medical providers by reading the testimonies of other patients who have had surgery abroad.

Medical tourism is only one aspect of the way globalization is changing the U.S. health care system. Apart from patient travel, many medical tasks can be outsourced to skilled professionals abroad when the physical presence of a physician is unnecessary. This can include interpretation of diagnostic tests and long-distance international collaboration, particularly in case management and disease management programs, because of the availability of information technology.

If American health care consumers are to benefit to the fullest extent from global health care competition, federal and state policies must allow them to take advantage of the opportunities. Legal reforms policymakers should consider include recognizing licenses and board certifications from other states and countries. The federal Stark laws limiting relationships between physicians and hospitals need to be modified to let health care providers offer integrated medical services, including follow-up care for patients returning from treatment abroad. Finally, the federal and state governments should lead by example by allowing Medicare and Medicaid programs to send willing patients abroad. Medicare in particular would benefit from cost savings due to its large volume of orthopedic and cardiac procedures.

[page]Global competition is emerging in the health care industry. Wealthy patients from developing countries have long traveled to developed countries for high quality medical care. Now, growing numbers of patients from developed countries are traveling for medical reasons to regions once characterized as “third world.” Many of these “medical tourists” are not wealthy, but are seeking high quality medical care at affordable prices. To meet the demand, entrepreneurs are building technologically advanced facilities outside the United States, using foreign and domestic capital. They are hiring physicians, technicians and nurses trained to American and European standards, and where qualified personnel are not available locally, they are recruiting expatriates.

[page]“Medical tourists are seeking high quality medical care at affordable prices.”

Medical tourism is growing and diversifying. Estimates vary, but McKinsey & Company and the Confederation of Indian Industry put gross medical tourism revenues at more than $40 billion worldwide in 2004. Others estimate the worldwide revenue at about $60 billion in 2006.McKinsey & Company projects the total will rise to $100 billion by 2012. [See Figure I.]

Internationally-known hospitals, such as Bumrungrad in Thailand and Apollo in India, report revenue growth of about 20 percent to 25 percent annually. McKinsey & Company estimates that Indian medical tourism alone will grow to $2.3 billion by 2012. Singapore hopes to treat 1 million foreign patients that year.

Reports on the number of patients traveling abroad for health care over the past few years are scattered, but all tell the same story. In 2005:

- Approximately 250,000 foreign patients sought care in Singapore, and 500,000 traveled to India for medical care.

- Thailand treated as many as 1 million foreign patients.

The foreign patients treated in these countries included some of the 500,000 Americans who traveled abroad for medical treatment that year.

Residents of countries with national health insurance, including Canada and the United Kingdom, often travel to other countries, including the United States, because they lack timely access to elective procedures due to rationing. In Canada, physicians cannot privately treat their fellow Canadians if those treatments are covered by the government health plan (Medicare). Also, national health systems sometimes deny treatment to particular patients (for example, because of age or physical condition), and some treatments may not be available to any patients (for example, because of cost).

However, for most medical tourists, including those from the United States, the reason for travel is financial. The effect of financial incentives on Americans' willingness to travel for medical care is shown by a recent nationwide survey.

- Almost no one would travel a great distance to save $200 or less.

- Fewer than 10 percent would travel to save $500 to $1,000.

- About one-quarter of uninsured people, but only 10 percent of those with health insurance, would travel abroad for care if the savings amounted to $1,000 to $2,400.

- For savings exceeding $10,000 about 38 percent of the uninsured and one-quarter of those with insurance would travel abroad for care.

“Medical tourists include residents of countries with national health insurance, where heath care is rationed.”

Some American medical tourists are seeking lower prices for treatments not covered by insurance (such as cosmetic surgery and weight loss surgery). Uninsured patients paying the cost out of their own pocket travel because American hospitals often charge cash-paying, uninsured individuals inflated “list” prices, which can be much higher than government or private insurers have to pay. Also, a small but growing number of insurers are creating health plans that encourage enrollees to shop for better prices among approved vendors in other countries and allow them to share in the savings. There are also potential savings for insured patients who bear some of the cost through copayments and deductibles. For example, if a procedure cost $4,000 less in another country, a patient required to pay 20 percent of the cost (through a copayment) would save $800 out of pocket.

Where Do Patients Seek Treatment? Most American medical tourists seek treatment in Mexico and other Latin American countries. Clinics in Brazil and Argentina have offered low-cost cosmetic surgery for years. India and Thailand are now promoting their high-tech facilities for more serious procedures, including hip and knee replacements and cardiac surgery. Other destinations include Singapore, Belgium and South Africa. Many Northern and Western Europeans travel to Central and Eastern Europe for low-cost medical and dental services. [See the sidebar, “Medical Tourism Destinations.”]

Cross-Border Medical Tourism. It may be impractical for sick Americans to travel to faraway places like India and Thailand for major surgery. But many types of medical services are available nearby — in Mexico and elsewhere in Latin America.

“Most American medical tourists seek treatment in Mexico and other Latin American countries.”

Mexico . Mexican physicians have a thriving business treating American (and Canadian) retirees searching for of low-cost drugs, dental care and physician services. Prices in Mexico are about 40 percent lower than in the United States. Cash-paying, uninsured Americans can find better deals on procedures in Mexico, including price quotes and package prices, which most American hospitals do not offer.

Indeed, some Arizona retirement communities have regular bus tours to take residents across the Mexican border for prescription drugs and dental care. Some health plans in Southern California offer lower premiums and copayments to patients who use network providers across the border in Tijuana. Facilities are being built in Mexican border towns to take advantage of these plans.

Dallas-based International Hospital Corp. operates four Mexican hospitals, three close to the U.S. border and one near Mexico City (it has other facilities in Brazil and Costa Rica). A Mexican partnership called Christus Muguerza is building and operating hospitals in Mexico that meet American standards. It has identified 40 communities along the U.S.-Mexican border where it intends to build facilities.

Some 40,000 to 80,000 American seniors live in Mexico. In addition to health care at lower prices (Medicare does not cover care outside the United States), a number of them receive nursing home care at bargain prices. In most areas of the United States, the cost of nursing home care can easily surpass $60,000 per year. But in Mexico, high quality long-term care costs only about one-fourth as much. For about $1,300 per month, a senior can get a studio apartment that includes laundry service, cleaning, meal preparation and access to around-the-clock nursing care.

Latin America . Costa Rica and Panama are popular destinations for medical travel. Around 150,000 foreigners sought care in Costa Rica in 2006. This is amazing, considering that Costa Rica is a country of only about 4 million people. By contrast, in 2006 just 250,000 foreigners sought care in the United States — a country with nearly 300 million more residents.

Panama has high quality health care, concentrated primarily in the metropolitan areas. Medical standards at Panama's top hospitals are comparable to those in the United States. Indeed, many Panamanian physicians were trained in the United States. Hospital Punta Pacifica in Panama City, Panama, is an affiliate of U.S.-based Johns Hopkins International. Medical care in Panama is 40 percent to 70 percent less expensive than in the United States.

Medical Tourism within the United States . Domestic medical travel involving patients seeking more advanced treatment facilities in other cities or states is relatively common. Specialty hospitals built to provide orthopedic and cardiac treatment attract patients from many communities. These facilities generally provide better quality care and higher patient satisfaction than general hospitals. Many patients travel great distances to receive care at the world-renowned Cleveland Clinic and the Mayo Clinic, two high quality health care providers.

[page]“Medical intermediaries help patients select physicians and hospitals.”

Patients who aren't familiar with specific medical facilities abroad can coordinate their treatment through medical travel intermediaries. Many intermediaries use the Internet to recruit patients. These services work like specialized travel agents. Clients of MedRetreat, for example, can choose from a menu of 183 medical procedures from seven different countries: India, Thailand, Malaysia, Brazil, Argentina, Turkey and South Africa.

“PlanetHospital charges a flat fee for medical intermediary services.”

Intermediaries investigate health care providers and screen customers to assess those who are physically well enough to travel. Some intermediaries are affiliated with specific medical providers and send patients exclusively to those providers. But most intermediaries seek to create a broad network of providers and destinations to meet the diverse needs of patients. For instance, some patients might prefer to pay a higher fee in exchange for less travel time, while others might be willing to travel greater distances to save money.

“Pricing is highly competitive for procedures that aren't covered by insurance.”

In addition, intermediaries often have doctors and nurses on staff to assess the medical efficacy of procedures and help patients select physicians and hospitals. For example, Medical Tours International, which sent more than 1,300 patients abroad in 2005, employs medical personnel to assist patients in trip planning and treatment decisions.

One of the best-known firms in the medical tourism industry is California-based PlanetHospital. [See the sidebar, “PlanetHospital.”]

Fees for treatments abroad range from one-half to as little as one-fifth of the price in the United States. In some cases prices are 80 percent lower abroad. Savings vary depending upon the destination country and type of procedure performed.

For example:

- Apollo Hospital in New Delhi, India, charges $4,000 for cardiac surgery, compared to about $30,000 in the United States.

- Hospitals in Argentina, Singapore or Thailand charge $8,000 to $12,000 for a partial hip replacement — one-half the price charged in Europe or the United States.

- Hospitals in Singapore charge $18,000 and hospitals in India charge only $12,000 for a knee replacement that runs $30,000 in the United States.

- A rhinoplasty (nose reconstruction) procedure that costs only $850 in India would cost $4,500 in the United States. [See Figure II.]

Patients can also find lower-priced nonsurgical procedures and tests abroad:

- An MRI in Brazil, Costa Rica, India, Mexico, Singapore or Thailand costs from $200 to $300, compared to more than $1,000 in the United States.

- six-hour comprehensive fitness exam — including an echocardiogram, stress test, lung-function test and ultrasound of internal organs — costs only $125 at India's Rajan Dhall Hospital; a similar battery of tests in the United States could easily top $4,000.

Why Are Foreign Hospitals Able to Offer Lower Prices? Prices for treatment are lower in foreign hospitals for a number of reasons.

Labor costs. In the United States, labor costs equal more than half of hospital operating revenue, on the average. Wage rates and other labor costs are lower overseas; specifics were not available, but as one example, at Fortis hospitals in India:

- Doctors earn about 40 percent less than comparable physicians in the United States.

- Median nurses' salaries are one-fifth to one-twentieth of those in the United States.

- The wages of unskilled and semiskilled labor, such as janitors and orderlies, are also much less.

“Prices are lower where patients pay out of pocket for health care.”

These lower labor costs make it much less expensive to build and operate hospitals in other countries.

Less (or No) Third-Party Payment. Markets tend to be bureaucratic and stifling when insurers or governments pay most medical bills. In the United States, third parties (insurers, employers and government) pay for about 87 percent of health care. So patients spend only 13 cents out of pocket for every dollar they spend on health care. As a result, they do not shop like consumers do when they are spending their own money, and the providers who serve them rarely compete for their business based on price.

A much higher percentage of private health spending is out of pocket in countries with growing, entrepreneurial medical markets. For instance, patients pay 26 percent of health care spending out of pocket in Thailand, 51 percent in Mexico and 78 percent in India. [See Figure III.] When patients control more of their own health care spending, providers are more likely to compete for patients based on price. Consequently, these countries have more competitive private health care markets.

In the United States, the markets for those medical services for which patients usually pay out of pocket, such as elective cosmetic surgery or vision correction (Lasik), are much more entrepreneurial and competitive. Patients control the dollars that pay for these procedures, so physicians compete with one another on price. For example, the cost of standard Lasik has fallen about 20 percent over six years.

“Package prices for services are common.”

Price Transparency and Package Pricing . One criticism of American hospitals and clinics is that prices are difficult to obtain and often meaningless when they are disclosed. Patients who ask potential providers to quote a price are likely to be disappointed. In fact, many people have little idea of the cost of medical treatments. A recent Harris Poll found:

Consumers can guess the price of a new Honda Accord within $1,000, but when asked to estimate the cost of a four-day hospital stay, those same consumers were off by $12,000!

- Furthermore, 68 percent of those who had received recent medical care did not know the cost until the bill arrived, and 11 percent said they never learned the cost at all.

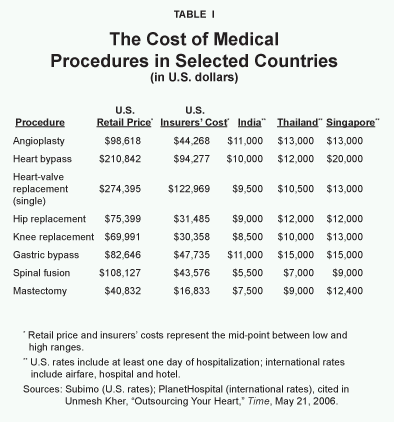

In the international health care marketplace, the situation is quite different. Package prices are common, and medical travel intermediaries help patients compare prices. [For examples, see Table I.]  Even providers who do not offer fixed pricing will provide reasonably accurate price quotes. As a result, medical centers and clinics that treat large numbers of medical tourists routinely quote prices in advance and look for ways to reduce patients' costs.

Even providers who do not offer fixed pricing will provide reasonably accurate price quotes. As a result, medical centers and clinics that treat large numbers of medical tourists routinely quote prices in advance and look for ways to reduce patients' costs.

“Cash-paying patients pay higher prices than insurers in most U.S. hospitals.”

Few Cross-Subsidies. In American full-service nonprofit general hospitals, revenues from treatments for some patients are used to cover the costs of providing treatments to other patients. This cross-subsidization is possible because some medical procedures produce more revenue than it costs to provide them. For example, the revenue from routine heart catheterization procedures or diagnostic imaging systems in a community hospital might be used to subsidize indigent health care or the cost of operating the emergency room. This means that a hospital's charges for the heart procedure more than cover its costs, but its charges for emergency room care do not cover those costs. If there is no competition for the business of heart patients in the hospital's service area, it can cross-subsidize without losing revenue.

However, a provider who does not cross-subsidize could offer the cardiac treatment for a lower price or could make a profit charging the same price. In the United States, such providers have emerged in the form of highly efficient specialty hospitals. Nonprofit community hospitals complain that specialty hospitals skim off lucrative surgeries but do not provide the services that community hospitals do, such as emergency departments and charity care for the uninsured. This has led to a moratorium on new specialty hospitals in the Medicare program.

Streamlined Services. Some foreign medical providers operate highly efficient “focused factories.” These are specialty clinics and hospitals where tasks and procedures have been streamlined for the highest efficiency — similar to the way a Toyota automotive plant operates. For example, Fortis Healthcare's Rajan Dhall Hospital in New Delhi uses a business model that combines the personalized service of the hotel industry with the industrial processes of an automaker — both industries in which its senior executives have experience. Jasbir Grewal, Rajan Dhall's vice president for operations, spent years working for the Hilton hotel chain. He describes their hospital as “a hotel providing clinical medical excellence.” Fortis chairman Harpal Singh, who came from the automotive industry, emphasizes the need to streamline processes in such a way that procedures can be performed quickly and efficiently.

Limited Malpractice Liability. Malpractice litigation costs are also lower in other countries than in the United States. While American physicians in some specialties pay more than $100,000 annually for a liability insurance policy, a physician in Thailand spends about $5,000 per year. Thailand does not compensate victims of negligence for noneconomic damages, and malpractice awards are far lower than in the United States.

“Foreign hospitals have fewer cost-increasing regulations and cross-subsidies.”

Fewer Regulations. Excessive health care regulations in the United States prevent American hospitals from making the sort of collaborative arrangements many international hospitals use. For instance, facilities abroad can structure physicians' compensation to create financial incentives for the doctors to provide efficient care, whereas American hospitals usually cannot. The reason: Physician compensation arrangements in American hospitals cannot violate the Stark (anti-kickback) laws.

Foreign hospitals can also employ physicians directly — a practice prohibited by many states. For instance, physicians in India contract with hospitals to provide a certain number of hours per month in return for a guaranteed fixed fee. Patients select the hospital based on reputation and then choose an appropriate doctor who works with the hospital. In this regard, physicians depend on hospitals for business rather than the other way around.

[page]Some American medical trade groups caution patients about the quality of treatment abroad. Speaking of foreign medical providers, Bruce Cunningham, president of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, told the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Aging, “Without a complete understanding of the medical standards for the health institution or facility, medical providers, surgical training, credentials, and postoperative care associated with surgery, a patient can be ill-informed — and worse, at significant risk.” In fact, Cunningham's warning could easily apply to U.S. hospitals as well. Information on quality is not readily available to patients, and what is available is often difficult to interpret or irrelevant.

“The quality of American hospitals varies widely.”

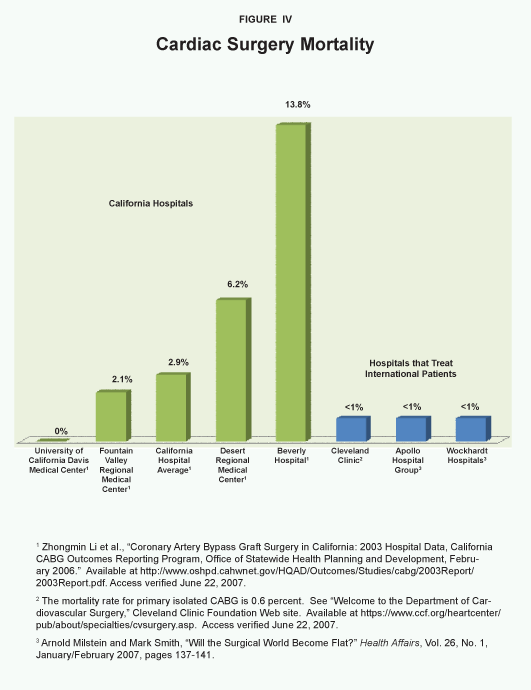

Measuring Quality. Despite claims of high U.S. standards, results vary widely by hospital. Consider one of the most commonly performed procedures in the United States today — coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery:

- Hospitals in California that perform CABG surgery have an average mortality rate of nearly 3 percent (2.91).

- The California average is nearly four times higher than the Cleveland Clinic, considered the best hospital in the nation by U.S. News & World Report .

Closer inspection of California hospitals shows wide variations in quality: [See Figure IV.]

- The University of California Davis Medical Center experienced no deaths among the 136 patients receiving CABG surgery in 2003.

- Fountain Valley's mortality rate of 2.14 percent was below the state average of 2.91 percent.

- But Desert Regional Medical Center, which performed a similar volume of surgeries, had a mortality rate of more than 6 percent — twice the California average and 10 times Cleveland Clinic's average.

- Beverly Hospital performs few CABG procedures, which may explain its high mortality rate of 13.79 percent.

“A number of foreign hospitals are accredited in the United States.”

How does the quality of facilities overseas compare to those in the United States? Some of the more prestigious providers, such as Apollo Hospital Group and Wockhardt Hospitals (which is affiliated with Harvard Medical School) in India, and Bumrungrad International Hospital in Thailand, offer a better level of care than the average community hospital in the United States. [See the sidebar on Bumrungrad.]

As in the United States, many hospitals abroad do not disclose recognized quality indicators. But most hospitals that compete on the international level generally do.

- Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center in New Hampshire and Ohio's Cleveland Clinic have quality indicators on their Web sites.

- National University Hospital Singapore also discloses information demonstrating that its quality compares very favorably internationally.

- India's Apollo Hospital Group has devised a clinical excellence model to ensure its quality meets international health care standards across all its hospitals.

Other Indian hospitals are working to create standards for reporting performance measures.

“Some American hospitals have foreign affiliates.”

Electronic Medical Records. Because potential medical tourists must first be evaluated remotely, most large health care providers and medical intermediaries for patients use electronic medical records (EMRs) to store and access patient files. Patients can then discuss the procedures with potential physicians via conference call. Modern hospitals abroad also use information technology to identify potential drug interactions, manage patient caseloads and store radiology and laboratory test results.

By contrast, only about one out of four U.S. hospitals store medical records electronically. Third parties pay 87 percent of medical bills in the U.S. health care system, and most of the third parties do not reimburse physicians or hospitals for the use of EMRs. Since others pay the bills, patients usually do not choose hospitals or physicians based on their use of EMRs.

“Some foreign hospitals have U.S. trained or U.S. certified physicians.”

Hospital Accreditation. More than 120 hospitals abroad are accredited by the Joint Commission International (JCI), an arm of the Joint Commission for the Accreditation of Hospitals that accredits American hospitals participating in Medicare. The International Standards Organization (ISO) also accredits hospitals that meet internationally agreed-upon standards. Nearly 150 foreign hospitals are accredited by ISO and JCI.

In addition, some countries are adopting their own accreditation standards. For instance, the Indian Healthcare Federation is developing accreditation standards for its members in an attempt to reassure potential patients about India's high quality health care.

Hospital Affiliation. Some foreign hospitals are owned, managed or affiliated with prestigious American universities or health care systems:

- The Cleveland Clinic owns facilities in Canada and Vienna, Austria; and in Abu Dhabi, the clinic already manages an existing facility and is building a new hospital.

- Wockhardt (India) is affiliated with Harvard Medical School.

- Hospital Punta Pacifica in Panama City, Panama, is an affiliate of U.S.-based Johns Hopkins International.

- JCI-accredited International Medical Centre in Singapore is also affiliated with Johns Hopkins International.

- Dallas-based International Hospital Corp. is building and operating hospitals in Mexico that meet American standards.

- Bumrungrad International Hospital in Thailand has an American management team to provide American-style care.

“Patients should check the credentials and quality of foreign providers.”

Physician Credentials. Foreign health care providers and medical travel intermediaries also compete on quality by touting the credentials of the medical staff. These physicians are often U.S. board-certified, while others have internationally respected credentials. Many of the physicians working with medical tourists were trained in the United States, Australia, Canada or Europe. Nearly two-thirds of the physicians who work with PlanetHospital have either fellowships with medical societies in the United States or the United Kingdom, or are certified for a particular specialty by a medical board.

Online Communities. Potential patients can get some idea of the safety and quality of medical providers by searching online for testimonies of patients who have had surgery abroad. These Internet communities facilitate the exchange of information about providers, including facility cleanliness, convenience, price, satisfaction with medical services and the availability of lodging while recuperating.

“Medical tourists can purchase malpractice insurance to obtain compensation for bad outcomes.”

PlasticSurgeryJourneys.com has built such a community. Members, including both former and prospective patients, can exchange information in online discussion forums on such topics as destinations, specific physicians and types of surgery. Members answer questions about side effects, complications and occasionally even discuss patients who have died from surgery. A few members who had cosmetic surgery have even posted before-and-after photos. If a facility performed low-quality work on a member, others in the community know to avoid the provider. For example, patients who were disfigured by Mexican cosmetic surgeons created a Web site (http://www.cirujanosplasticos.info) to warn away other patients. HealthMedicalTourism.org is another Web site with a forum where members can interact. Authors of books on medical tourism also interact with readers online. Jeff Schult, author of Beauty From Afar , has links to articles, reviews and a blog where readers can comment on topics of interest.

When Things Go Wrong. Even with the most skilled physicians, patients may have adverse outcomes. When a medical tourist experiences injury or even death, it is natural to wonder whether a poorly trained physician or substandard hospital played a part. Of course, sometimes adverse events are due to the patient's pre-existing health conditions or other factors not the fault of the physician; but, as with any service providers, doctors aren't perfect.

Little evidence exists to indicate that botched operations are a widespread problem in the medical tourism industry. Anecdotal evidence tends to involve cosmetic surgery patients who went to facilities that were not screened by a respected intermediary or whose physicians' credentials were not checked.

Sometimes complications from cosmetic surgery are due to a patient's having too many procedures performed too soon. Most American physicians advise against multiple or consecutive cosmetic surgeries in a short period of time. But patients often have limited time off from work and consider travel and recuperative time as part of the cost of surgery. Thus they are tempted to economize by having more work done than is medically recommended.

Some foreign physicians entice patients with package deals that combine multiple surgeries for one low price. It is not uncommon for South American doctors to offer package prices that include full body liposuction, a breast lift or augmentation (with implant) and a tummy tuck. The package price can be as low as $6,500 (plus travel and lodging) in Colombia, Costa Rica or Mexico. The comparable surgery costs $12,000 to $15,000 — and sometimes as much as $30,000 — in the United States. Women who receive that much cosmetic surgery at one time often find recuperation slow and extremely painful. They may also need postoperative monitoring in a clinic for several days with intravenous antibiotics and blood transfusions, all of which can add several thousand dollars to their cost.

The Web-based intermediaries mentioned elsewhere in this study could help potential patients more carefully choose a destination and physician through a rating system similar to those found for travel and hotels on eBay, Orbitz, Travelocity or Expedia. A rating system would help steer patients to facilities that have more satisfied customers. Health care providers that fail to supply the quality and level of service American patients expect would be blackballed, or at the very least learn valuable lessons about what patients want.

Foreign laws governing medical liability are not as strict as those in the United States, nor is malpractice compensation as generous. Foreign physicians typically do not carry the same level of malpractice insurance as do American physicians. The threshold for malpractice is higher outside the United States, and there is limited recourse through the court system in some countries. Injured patients may not even have the right to sue at all.

Moreover, a medical tourist would have no recourse through the American court system. It is doubtful an American court would hold an intermediary liable since medical tourism “matchmakers” are not health care providers, and, thus cannot commit malpractice.

Reputable facilities abroad will work hard to prevent and correct problems. Although it rarely happens, patients may have to travel back for follow-up care if they do not have a U.S. physician willing to provide it. A patient may travel overseas again because the cost of treating unexpected complications is lower abroad. Additionally, some providers include treatment for complications in their package price.

Medical Malpractice Insurance by Contract. Medical tourists who have little recourse in foreign courts when malpractice occurs have another option: They can purchase a medical malpractice policy that pays in the event a procedure is botched from AOS Assurance Company Limited, an insurer based in Barbados.

One of the ways AOS ensures quality (and reduces its risk) is by covering only procedures performed in accredited hospitals by credentialed physicians. For instance, an American patient needing angioplasty can obtain $250,000 of coverage for a fee of $1,124.55. A patient wanting $100,000 in financial protection against a botched facelift would pay $225. In the event of medical malpractice, AOS Assurance Company Limited will compensate insured patients or their beneficiaries for lost wages, repair costs, out-of-pocket expenses, rehabilitation, severe disfigurement, loss of reproductive capacity and death. Claims are administered by an independent, Canadian-based firm, Crawford & Company.

[page]For the United States, globalization of health care encompasses both exporting patients (medical tourism) and importing medical services (outsourcing). This medical trade has the potential to increase competition and efficiency in the United States. Princeton University health economist Uwe Reinhardt says the effect of global competition on American health care could rival the impact of Japanese automakers on the U.S. auto industry — forcing domestic producers to improve quality and to offer consumers more choices.

Apart from patient travel, many medical tasks can be outsourced to skilled professionals abroad when the physical presence of a physician is unnecessary. This can include long-distance collaboration — incorporating the services of foreign medical staff into the practices of American medical providers. Finally, global competitors can build facilities closer to the United States and selectively contract with U.S. health insurers.

Outsourcing Medical Services. Information technology makes it possible to provide many medical services remotely, including outsourcing them to other countries. Telemedicine — the use of information technology to treat or monitor patients remotely by telephone, Web cam or video feed — is becoming common in areas where physicians are scarce. It gives rural residents access to specialists and will probably become the preferred way to monitor patients with chronic conditions.

Outsourcing often results in lower costs, higher quality and greater convenience. Some clerical tasks, such as medical transcription — entering physician notes and dictation into a patient's electronic medical record — are already outsourced. American hospitals increasingly use radiologists in India and other countries to read X-rays. For instance, NightHawk Radiology Services contracts with American board-certified physicians living in Australia for overnight interpretations of X-rays and scans. Other medical tasks that don't require the physical presence of a physician could also be outsourced to lower-cost doctors abroad. The British National Health Service (NHS) is considering using doctors in India to read some lab tests and MRI scans.

PlanetHospital has offered to work with U.S. hospitals to set up local imaging centers that would use physicians in India to read imaging scans. An MRI scan could be performed profitably for as little as $400 to $500 — far less than typical U.S. prices.

“Outsourcing some medical tasks can reduce costs and improve quality.”

Opportunities for American and Foreign Health Care Providers to Collaborate. Helping patients properly manage a chronic condition is often complex and time consuming. Outcomes could be improved if teams of medical providers worked together to improve all aspects of medical treatment through aggressive management.

When multiple physicians are treating a patient, a case manager could ensure that all physicians are coordinating their efforts. However, such close monitoring and interaction is labor-intensive and costly. Often these tasks are not reimbursed or are reimbursed at rates lower than the cost of providing them. A potential solution is for American health care providers to collaborate with low-cost providers in developing countries by having them perform these labor-intensive tasks that don't require the physical presence of a physician.

Telemedicine, which involves remote consultation, monitoring and treatment of patients, is increasingly being used in disease management programs. Past research has already shown that telemedicine can improve adherence to protocols and increase convenience for patients with chronic ailments. Thus, it is a logical to outsource some of disease management or remote health coaching to places where labor costs are lower.

Creating New Heath Insurance Plans that Cover Medical Travel. Currently, most insurers do not include foreign providers in their networks, but they may in the future. Mercer Health, an employee benefits consulting firm, is working with several Fortune 500 employers to take advantage of medical travel. Several health insurers are also experimenting with international coverage. Milica Bookman, a professor at St. Joseph University, predicts that by 2009, it will become increasingly common for mainstream health insurers to include foreign providers in their networks. The following are some examples of insurance products that already use foreign providers.

Access Baja .BlueShield of California has a health network designed for people who choose to get their medical care in Mexico. Access Baja was implemented a year after California passed legislation in 1999 allowing the state's insurers to reimburse providers in Mexico. Although many of the enrollees are Mexican nationals who cross the U.S. border each day to work, employers on both sides of the border can offer this plan to their workers. However, the plan requires enrollees to live within 50 miles of the border to easily access the Mexican primary care physicians in the BlueShield network. By 2005, nearly 40,000 people had signed up for coverage offered by Mexican health care providers.

Because Mexican medical care costs less, Access Baja premiums are less than two-thirds the cost of the alternative BlueShield of California plans. Hispanic enrollees can have a doctor who is fluent in Spanish and understands their culture. An added convenience is that Mexican physicians are often available for same-day appointments, as well as evenings and on weekends.

“Some health plans cover treatment in foreign countries.”

Networks with Foreign Hospitals. Some health plans take advantage of the potential in allowing enrollees to travel abroad for lower-cost treatments. In February 2007, BlueCross BlueShield of South Carolina added Bumrungrad International Hospital in Thailand to its network. South Carolina BlueCross BlueShield does not plan to require patients to go abroad for lower-cost care, nor is it actively considering using financial incentives to encourage patients to travel abroad. Rather it is a value-added service available to members who request it. While no patients have thus far taken advantage of this service, it may benefit underinsured patients facing steep out-of-pocket payments.

Other Options . As the medical tourism trend grows, other U.S.-based companies in the health industry are looking at ways to offer medical travel that is at least partially covered by health insurance.

- Over the next few years,at least 40 company-sponsored health plans will offer overseas options through United Group Programs, a health insurer in Boca Raton, Florida.

- In 2006, West Virginia's legislature held hearings on the possibility of including foreign hospitals in its state employees' health plan network.

- And the medical tourism firms IndUSHealth and PlanetHospital are in the process of creating health insurance products that combine American-based primary care with foreign travel for expensive procedures.

PlanetHospital . PlanetHospital is working with a major insurer to design a low-cost health plan. Initially, PlanetHospital plans to roll out a limited benefit plan, sometimes referred to as a “mini-med” plan, based on the casualty insurance model where the benefit is a specific sum of money. These types of plans generally provide coverage for a limited number of physician visits each year, a limited amount of inpatient care and sometimes coverage for prescription drugs. Mini-med policies typically cap benefits at a maximum of about $25,000 annually. Since the amounts these policies will pay are relatively low, patients can expect significant cost-sharing for medical care. But this provides an incentive for patients to carefully shop to avoid high out-of-pocket costs.

“New health plans offer a fixed payment per procedure to encourage patients to shop for health care.”

The unique part of PlanetHospital's plan is that it will reimburse patients the same amount for each particular service, regardless of where it is performed. Thus a patient could significantly lower out-of-pocket costs by going abroad for treatment. For instance, an enrollee who needs a heart procedure could easily spend more than $50,000 at a hospital in the United States. A mini-med policy may pay only $10,000 toward the cost. But abroad, the same surgery could cost less than $10,000, including travel, thus making the mini-med a sensible and affordable alternative. Because coverage is limited, this policy will cost about $50 to $100 a month, only a fraction of a traditional health plan .

PlanetHosptial's first step will be a health plan aimed at El Salvadorans living in the United States. Enrollees would receive a limited number of primary care visits locally under the plan and could travel to El Salvador for covered major medical needs. If the plan proves successful, additional ones will follow for countries such as Mexico and India. Coverage under one of these “mini-med” plans might cost a family as little as $200 per month.

Effects of Increased Competition on U.S. Health Care Markets. Global competition could lower the cost of some medical procedures. At the same time, increased international competition for qualified medical personnel could raise labor costs in the United States. If foreign medical students, physicians and nurses currently in America choose to work overseas, there may be shortages of workers in some medical specialties in the United States, and wages for these workers will rise. This is especially likely in areas of medicine not easily outsourced. For example, radiology is relatively easy to outsource since it does not require the radiologist to be physically present. Although radiology has been one of the highest-paid specialties in medicine, that is likely to change in the future since reading X-rays and other scans can easily be outsourced. On the other hand, outsourcing would have little effect on the inherently local practice of emergency room medicine.

Global medical competition could also exacerbate the shortage of primary care physicians in the United States. Today nearly one-quarter of practicing physicians in the United States attended a foreign medical school. Indeed, each year nearly one-quarter of slots in U.S. medical residency programs are filled by foreigners. Greater opportunities in their native countries and in other countries could reduce the number of foreign physicians (and nurses) practicing in the United States. It could also encourage more of them to return home after they receive training. Many foreign medical graduates work in underserved rural areas, so these communities would be especially hard hit.

Also, due to an ongoing nursing shortage, American hospitals recruit foreign nurses to fill vacancies. A smaller supply of foreign physicians and nurses willing to work in the United States could strain the U.S. health care system by raising labor costs.

Effects of Globalization on Health Care in Other Countries. Today many African countries are experiencing shortages of physicians and nurses. Because of the opportunity to earn more in Europe and the United States, many physicians trained in Africa emigrate. More opportunities to work, higher pay and entrepreneurial opportunities in developing countries could reduce this brain drain. This would benefit the local populations by increasing their access to care.

Critics in developing countries claim that health care facilities and providers that serve medical tourists will treat only foreign patients to the exclusion of native-born poor residents. This is unlikely, since most hospitals in developing countries cannot survive on cash-paying medical tourists alone. But even if specific hospitals in developing countries are open only to foreigners and local elites, the health care systems of these countries will be enriched by the influx of revenue, enabling them to offer local populations increased access to medical care.

[page]Health care globalization, including medical tourism and medical outsourcing, has the potential to lower costs and increase competition in the American health care industry. However, there are numerous obstacles to incorporating foreign health care providers into the U.S. health care system. Some of these barriers are the result of entrenched interest groups that do not want to compete with low-cost providers. Federal and state laws also create a number of obstacles to Americans seeking treatment abroad, including outdated laws supposedly intended to protect consumers that now merely increase costs and reduce convenience. Finally, state and federal regulations currently restrict public providers from outsourcing expensive medical procedures.

“Medical tourists provide resources to improve health care in developing countries.”

In addition, federal regulations make it difficult for private plans to offer financial rewards to enrollees willing to seek care abroad. This is significant because insurance pays the bills for most U.S. patients and surveys find that patients are unwilling to travel long distances for health care of the same quality they could receive at home unless they have a financial incentive to do so.

State Licensing Laws. Recent advances in information technology allow a radiologist to read X-rays from India just as easily as an American radiologist could read them from a home office. However, the practice of medicine is regulated by state medical boards, which generally require a physician to be licensed in the state where the patient receives treatment. Thus, state licensing laws prevent medical tasks from being performed by providers living in other states or countries. Foreign physicians also lack the authority to order certain tests, initiate therapies and prescribe drugs that American pharmacies can legally dispense.

“State regulations prevent out-of-state doctors from treating patients.”

States license and regulate physicians with the ostensible goal of maintaining the quality of medical care. However, state medical boards are dominated by physicians and, like the boards governing other regulated professions, they tend to benefit the practitioners. Besides stringent licensing requirements, these organizations suppress competition among physicians by declaring certain practices to be unethical. Medical societies have long opposed innovations that pose a threat to their autonomy or income. And threats to hospital revenue or the ability of hospital systems to cross-subsidize uncompensated care generate considerable opposition.

Some restrictions on the practice of medicine have been removed in recent years, but many still exist. For example:

- It is illegal for a physician to consult with a patient online without an initial face-to-face meeting.

- It is illegal in most states for a physician outside the state who has examined a patient in person to continue treating the patient via the Internet after the patient returns home.

- It is illegal in most states for a physician outside the state to consult by phone with patients residing in the state if the physician is not licensed to practice medicine there.

These laws make it difficult for American patients to seek care from doctors abroad via telephone and the Internet.

Restrictions on Collaboration among Health Care Providers. A physician practice in the United States could easily provide doctor visits in a traditional office, coupled with chronic disease management services from a foreign doctor and tests done at a convenient retail clinic when needed. Yet this scenario might run afoul of the so-called Stark laws. The federal Stark laws make it illegal for a physician to refer a patient for treatment to a clinic in which the doctor has a financial interest. It is also illegal for a physician to reward providers who refer patients to him, or to a hospital in which he has a financial interest. Unfortunately, laws meant to prevent self-dealing and kickbacks also inhibit beneficial collaborationbetween doctors and hospitals. For instance, the Stark laws could prevent a physician practice from referring a patient with a chronic condition to an affiliated disease management program (employing a foreign doctor) or prevent the practice from referring a patient needing minor treatment to an affiliated walk-in clinic.

By limiting compensation arrangements for referrals and collaboration, the Stark laws tend to result in rigid physician group practices that are not particularly convenient or economical for patients.

“Some physicians are reluctant to provide follow-up care for patients treated abroad.”

Lack of Follow-Up Care. Some procedures require follow-up care to monitor the healing process or remove stitches. In some cases, patients who have traveled abroad for medical procedures have problems finding a local physician willing to provide postoperative follow-up care. This is especially worrisome if the patient has complications. Liability for another provider's work is a perceived risk to doctors providing aftercare — one reason some American physicians are loath to provide follow-up care to patients treated abroad.

Another reason for physicians' reluctance to provide follow-up care is that patients treated abroad often lack insurance. Over the years, many doctors have assumed that health insurance is the only way for patients to finance medical care. Physicians may prefer not to treat uninsured patients (unless payment is made in advance) for fear they will not get paid.

Although lack of follow-up care is definitely a concern, many patients who have had surgery abroad report their regular doctor continued to treat them throughout recovery. Patients with a regular physician will likely fare better than those who are only seeking physician care for a short-term (postoperative) need.

“Government health programs could save money from medical globalization.”

Legal Obstacles. Employers and insurers could lower their health costs by sending employees abroad for treatment. However, there are important legal considerations. Plan sponsors must meet Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) fiduciary obligations in designing and managing employee benefit plans. According to some legal scholars, an employer that sponsors a health plan offering workers a financial incentive to travel abroad for treatment could have greater liability risks. The concern is that financial incentives might induce enrollees to accept substandard care when they otherwise would select the local hospital of their choice although many health plans do just that by offering financial incentives for patients to choose hospitals in their networks. If health plans cannot offer enrollees financial incentives, patients are unlikely to consider medical travel.

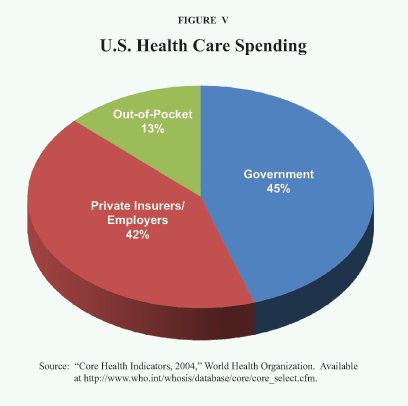

Federal and State Government Plan Obstacles. Nearly half of all health care expenditures in the United States are paid for by government. [See Figure V.]  This includes Medicare, Medicaid and health coverage for state and federal workers. It is hard to imagine significant cost savings occurring without involving the public sector.

This includes Medicare, Medicaid and health coverage for state and federal workers. It is hard to imagine significant cost savings occurring without involving the public sector.

“Health should be able to offer finanical incentives for patients to shop for health care.”

Medicaid consists of 50 different state programs. State Medicaid programs near the border with Mexico could easily outsource some procedures abroad. Yet despite the potential savings for state taxpayers, none have considered taking this step. Medicare benefits are limited to the United States. This is a hardship on foreign-born workers who accrue benefits in the United States but want to return to their homelands to retire. This also forces the estimated 40,000 to 80,000 American retirees living in Mexico to pay out of pocket or return to the United States to receive care. Furthermore, Medicare requires significant patient cost-sharing, generally 20 percent above the deductible. Medicare could reduce costs and allow seniors to share in the savings by waiving the cost-sharing requirements.

[page]The first step is for state and federal policymakers to understand that global competition in health care will benefit American consumers by reducing costs and improving quality through competition. Just as global competition improved the quality of automobiles, it will also improve the quality of medical care. Local politicians and community activists often fight to protect community hospitals from closure in the belief that communities cannot do without them. However, lawmakers must take advantage of cost-saving techniques in health care. States that border Mexico could follow California's lead and allow insurers to offer policies that include providers in Mexico. States that border Canada could follow suit.

Modernize State Licensing Laws. Medical licensing laws must conform to the information age, where distance (or country) is irrelevant. Reforms should include recognizing standards of other countries as an alternative to local licenses. For instance, many Indian and Thai physicians are board-certified or licensed in the United Sates, Australia, Britain or Canada. Foreign physicians who meet standard criteria should be considered licensed if their skills have been evaluated and approved for inclusion in a network. It does not make sense in the information age for each state to approve and police physicians living thousands of miles away. The same holds true for physicians practicing in the United States. Laws that prevent physicians in one state from consulting with patients in other states by telephone or e-mail should also be eased.

“Collaboration between American and foreign health providers would reduce costs and improve quality for U.S. patients.”

Relax Laws Restricting Collaboration. The federal Stark laws prohibiting self-referral should be modified to allow beneficial arrangements where care is coordinated and provided in a more efficient manner. Without revised legislation, it would be difficult to integrate the services of physicians living abroad into the practices of local providers. Integrated medical services would also allow domestic providers to compete by creating more efficient operations. For example, a traditional physician practice could offer disease management for chronic conditions at a lower cost through an associated Indian physician. And an American radiologist might have an Indian radiologist read X-rays at costs lower than competitors.

Encourage Follow-Up Care. While physicians prefer an ongoing relationship with a patient, outsourcing patients to providers abroad is not much different than referring them to a specialist down the street. If “safe harbor” contracts were created for physicians providing follow-up care, more doctors would be willing to treat cash-paying patients. Moreover, if the number of medical tourists rises significantly, entrepreneurial physicians and clinics will sense an opportunity to provide follow-up care. To facilitate providing follow-up care for patients who return from treatment abroad, a committee of the American Medical Association has recommended creating a current procedural terminology (CPT) reimbursement code for patients who need postoperative follow-up care.

Facilitate Liability by Contract. Some American patients may be concerned about the potential difficulty of holding providers accountable in foreign legal systems (malpractice liability) and of receiving compensation for complications that will undoubtedly arise from medical treatment abroad.. Federal law needs to recognize patient contracts that provide for binding arbitration or that limit liability. For instance, patients could purchase additional insurance from their health insurer in an amount they believe will protect them in the event of predefined problems that might occur from foreign treatment. A policy could clearly identify financial remedies for specific problems similar to an accidental death and dismemberment policy.

“Financial incentives would allow patients to share the savings from globalization.”

Allow Financial Incentives. Lately, some insurers have begun creating low-cost health plans that rely on foreign-based providers to treat serious ailments. Unfortunately, lawyers could interpret ERISA and HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) regulations in ways that discourage employers (and health plans) from providing patients with financial incentives to travel abroad for lower-cost care. Insurers and self-insured employers should have the right to experiment with a range of health benefits that inject global competition into health care. In addition, insurers, health plans and self-insured employers that have facilitated the overseas treatment of willing patients should be protected from liability.

Lead by Example. The federal and state governments should lead by example by allowing Medicare and Medicaid programs to send willing patients abroad. Medicare would particularly benefit from cost savings since it pays for a large volume of orthopedic and cardiac procedures.

[page]The number of uninsured and self-pay patients traveling abroad for health care has grown rapidly over the past few years. This trend is likely to continue as medical care becomes more expensive or difficult to obtain in countries such as the United States where third-party payment is the norm. It is unrealistic to assume that every American will travel abroad for medical care. But it doesn't require huge numbers to induce change. If only 10 percent of the top 50 low-risk treatments were performed abroad, the U.S. health care system would save about $1.4 billion annually. As more insured patients begin to travel abroad for low-cost medical procedures, medical tourism will result in competition that is sorely needed in the American health care industry.

NOTE: Nothing written here should be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of the National Center for Policy Analysis or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before Congress.

[page]- McKinsey & Company and the Confederation of Indian Industry, cited in Laura Moser, “The Medical Tourist,” Slate , December 6, 2005, and Bruce Stokes, “Bedside India,” National Journal , May 5, 2007.

- See Dudley Althaus, “More Americans Seeking Foreign Health Care Services,” Houston Chronicle , September 4, 2007.

- McKinsey & Company and the Confederation of Indian Industry, cited in Laura Moser, “The Medical Tourist,” and Bruce Stokes, “Bedside India.”

- Mark Roth, “$12 for a Half Day of Massage for Back Pain,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 10, 2006.

- McKinsey and the Confederation of Indian Industry, Press Trust of India, 2005.

- Joshua Kurlantzick, “Sometimes, Sightseeing Is a Look at Your X-Rays,” New York Times , May 20, 2007.

- “Medical Tourism Growing Worldwide,” U Daily (University of Delaware), July 25, 2005. Available at http://www.udel.edu/PR/UDaily/2005/mar/tourism072505.html. Accessed May 22, 2007.

- Malathy Iyer, “India Out to Heal the World,” Times of India, October 26, 2004.

- Jessica Fraser, “Employers Increasingly Tapping Medical Tourism for Cost Savings,” News Target , November 6, 2006.

- “Who Can Have Fertility Treatment?” BBC Health, undated. Available at http://www.bbc.co.uk/health/fertility/features_whocan.shtml. Accessed April 30, 2007. Also see “Cost of Fertility Treatment,” 2006. Available at http://www.gettingpregnant.co.uk/cost_information.html. Accessed April 30, 2007.

- Arnold Milstein and Mark Smith, “Will the Surgical World Become Flat?” Health Affairs , Vol. 26, No. 1, January/February 2007, pages 137-41.

- Arnold Milstein and Mark Smith, “America's New Refugees — Seeking Affordable Surgery Offshore,” New England Journal of Medicine , Vol. 355, No. 16, October 19, 2006.

- Neal Conan (host), “Outsourcing Surgery,” National Public Radio, Talk of the Nation, March 8, 2007. Available at http://www.npr.org/blogs/talk/2007/03/outsourcing_surgery.html. Accessed April 13, 2007.

- Diana M. Ernst, “Medical Tourism: Why Americans Take Medical Vacations Abroad,” Pacific Research Institute, Health Policy Prescriptions, Vol. 4, No. 9, September 2006.

- Beverly Blair Harzog, “Medical Tourism Offers Healthy Savings,” Bankrate.com, March 23, 2007.

- “Point of View: Eastern Europe,” HealthAbroad.net. Available at http://healthabroad.net/blog/?cat=8. Access verified June 22, 2007.

- Although many Americans patronize Mexican physicians, it is most common for seniors to cross the border for cheaper drugs, opticians and dentists. See Milan Korcok, “Cheap Prescription Drugs Creating New Brand of U.S. Tourist in Canada, Mexico,” Canadian Association Medical Journal , Vol. 162, No. 13, June 27, 2000; Steven Gluck “Bargain Dentistry — Wooden Teeth Anyone?” eZinearticles.com , February 22, 2006. Available at http://ezinearticles.com.

- For instance, in the United States 97 percent of hospital charges are paid by third parties. Devon M. Herrick and John C. Goodman, “The Market for Medical Care: Why You Don't Know the Price; Why You Don't Know about Quality; And What Can Be Done about It,” National Center for Policy Analysis, Policy Report No. 296, March 12, 2007.

- Manuel Roig-Franzia, “Discount Dentistry, South of the Border,” Washington Post , June 18, 2007.

- Devon Herrick, “Health Plans Adding Foreign Providers to Their Networks,” Health Care News , July 1, 2007. Also see Fraser, “Employers Increasingly Tapping Medical Tourism for Cost Savings.”

- Roig-Franzia, “Discount Dentistry, South of the Border.”

- Alfredo Corchado and Laurence Iliff, “Good Care, Low Prices Lure Patients to Mexico,” Dallas Morning News , July 28, 2007.

- Ibid.

- Chris Hawley, “Seniors Head South to Mexican Nursing Homes,” USA Today , August 16, 2007.

- Devon Herrick (moderator), Milica Bookman and Rudy Rupak, “Global Health Care: Medical Travel and Medical Outsourcing,” National Association for Business Economics, Health Economics Roundtable Teleconference, July 25, 2007. Available at http://www.nabe.com/podcasts/070725hrt.mp3. Accessed July 27, 2007.

- Figures for July 2005. See “World Factbook: Costa Rican People,” Yahoo.com, 2007.

- “Health Care in Panama,” International Living , undated. Available at http://www.internationalliving.com/panama/healthcare.html. Accessed July 27, 2007.

- Catherine Keogan, “Panama's Health Tourism Boom,” EzineArticles , May 31, 2007.

- There is currently a moratorium on building new specialty hospitals because it is thought they drain away lucrative, less acute cases from community hospitals. Yet there is little debate that this competition improves quality. For a discussion of specialty hospitals, see Leslie Greenwald et al., “Specialty Versus Community Hospitals: Referrals, Quality, And Community Benefits,” Health Affairs , Vol. 25, No. 1, January/February 2006.

- Some of these include: GlobalChoiceHealthCare.com, MediTourInternational.com, Indomedics.com, QuestMedTourism.com, MeritGlobalHealth.com, MyCareWeb.com, MedJourneys.com, HealthBase.com, MeSisOnline.com, GlobalMedicalServices.us, MedSourceIntl.com, MedicalNomad.com, AxiomHealth.org, HealthTraveler.net, HospitalBiblicaMedicalTourism.com, MyNovus.com, Medical-Tourism.FiveSites.com, 5Greatest.com, Surgicalcareinternational.com, Companionglobalhealthcare.com, Thailandvacationtour.com, Virginia.IQmedica.com, UniversalSurgery.com, Medical-Tourism-Guide.com, Bairesalud.com, TreatMeAbroad.com, Medical-travel-asia-guide.com and MediTourIndia.net.

- Krysten Crawford, “Medical Tourism Agencies Take Operations Overseas,” Business 2.0 Magazine , August 3, 2006.

- Julie Davidow, “Cost-Saving Surgery Lures ‘Medical Tourists' Abroad,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer , July 24, 2006.

- Jennifer Alsever, “Basking on the Beach, or Maybe on the Operating Table,” New York Times , October 15, 2006.

- Sarah Dawson with Keith Pollard, “Guide to Medical Tourism,” TreatmentAbroad.net, 2007; and http://www.cosmeticplasticsurgerystatistics.com/costs.html.

- At an average of about $1,038, an MRI for breast cancer screening costs about 10 times more than a mammogram. See Sylvia K. Plevritis et al., “Cost-Effectiveness of Screening BRCA1/2 Mutation Carriers with Breast Magnetic Resonance Imaging,” Journal of the American Medical Association , Vol. 295, No. 20, May 24/31, 2006, Table 3. Also see Devon Herrick, “Medical Tourism Prompts Price Discussions,” Health Care News, October 1, 2006.

- Bruce Stokes, “Bedside India,” National Journal, May 5, 2007.

- Steven Berger, “Analyzing Your Hospital's Labor Productivity,” Healthcare Financial Management , April 2005.

- Bruce Stokes, “Bedside India.”

- Ibid.

- Herrick and Goodman, “The Market for Medical Care.”

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “National Health Expenditures by Type of Service and Source of Funds: Calendar Years 2004-1960,” Department of Health and Human Services, 2006.

- “Core Health Indicators, 2004,” World Health Organization. Available at http://www.who.int/whosis/database/core/core_select.cfm.

- Herrick and Goodman, “The Market for Medical Care.”

- Julie Appleby, “Ask 3 Hospitals How Much a Knee Operation Will Cost … and You're Likely to Get a Headache,” USA Today , May 9, 2006.

- See “2006 Consumer Attitudes Survey,” Great-West Healthcare, 2006. Available at http://www.greatwesthealthcare.com/C5/StudiesSurveys/Document%20Library/m5031-gwh-consumer-attud-survy-06.pdf. Access verified May 21, 2006.

- Herrick and Goodman, “The Market for Medical Care.” For more about competition, bundling and repricing services, see Michael E. Porter and Elizabeth Olmsted Teisberg, Redefining Health Care: Creating Value-Based Competition on Results (Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business School Press, 2006).

- Since Medicare patients are an important source of revenue for many physicians and hospital networks, the moratorium has effectively prevented the opening of new specialty hospitals. See Bonnie Booth, “AMA: Don't Extend Moratorium on Specialty Hospitals,” American Medical News , December 27, 2004.

- For a discussion of new techniques in hospital efficiency, see Vanessa Fuhrmans, “A Novel Plan Helps Hospital Wean Itself Off Pricey Tests,” Wall Street Journal , January 12, 2007.

- Stokes, “Bedside India.”

- Ibid.

- Mark Roth, “Surgery Abroad an Option for Those with Minimal Health Coverage,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 10, 2006.

- State laws that ban the so-called corporate practice of medicine are the result of medical societies' attempts to maintain control over the practice of medicine.

- For a list of issues patients should consider, see Sidney M. Wolfe, Editor, “Patients without Borders: The Emergence of Medical Tourism, Part 2,” Public Citizen Health Research Group, Health Letter , Vol. 22, No. 9, September 2006.

- Bruce Cunningham, President of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, Statement Before the Special Committee on Aging, United States Senate, June 27, 2006. Available at http://aging.senate.gov/events/hr159bc.pdf. Access verified June 22, 2007.

- Zhongmin Li et al., “Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery in California: 2003 Hospital Data, California CABG Outcomes Reporting Program, Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, February 2006.” Available at http://www.oshpd.cahwnet.gov/HQAD/Outcomes/Studies/cabg/2003Report/2003Report.pdf. Access verified June 22, 2007. Some international hospitals, including Apollo Hospital Group, Wockhardt Hospitals and Escorts Health Institute (all in India), claim cardio bypass graft surgery mortality rates of less than 1 percent. A recent study found high-volume California hospitals have a mortality rate of nearly 3 percent. For more information, see Milstein and Smith, “Will the Surgical World Become Flat?”

- The mortality rate for primary isolated CABG is 0.6 percent. See Cleveland Clinic Foundation Web Site. Available at https://www.ccf.org/heartcenter/pub/about/specialties/cvsurgery.asp. Access Verified June 22, 2007.

- Ibid and Zhongmin Li et al., “Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery in California: 2003 Hospital Data, California CABG Outcomes Reporting Program, Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, February 2006.” Available at http://www.oshpd.cahwnet.gov/HQAD/Outcomes/Studies/cabg/2003Report/2003Report.pdf. Access verified June 22, 2007.

- Harvard Medical International's Web site is http://www.hmi.hms.harvard.edu/about_hmi/overview/index.php.

- See http://www.dhmc.org/qualitymeasures/ and http://www.clevelandclinic.org/quality/outcomes/.

- “Recognition of Our Clinical Achievements,” National Healthcare Group (Singapore), 2006, Clinical Quality Measures.

- Apollo Hospital Group Web site. Available at http://www.apollohospitals.com/QualityAssurance.asp. Access verified June 22, 2007.

- Herrick, “Medical Tourism Prompts Price Discussions.”

- These hospitals used the Global Care Solutions' software.

- Richard Hillestad et al., “Can Electronic Medical Record Systems Transform Health Care?” Health Affairs , Vol. 24, No. 5, September/October 2005, pages 1,103-17.

- Herrick and Goodman, “The Market for Medical Care.”

- Joint Commission International Web site: http://www.jointcommissioninternational.com/

- Julie Appleby and Julie Schmit, “Sending Patients Packing,” USA Today , July 27, 2006. Since this article appeared, the Joint Commission has accredited nearly 50 additional foreign hospitals.

- The Indian Healthcare Federation is made up of about 60 hospitals. See “Indian Hospitals Lure Foreigners with $6,700 Heart Surgery,” Bloomberg News , January 27, 2005.

- Communication between NCPA president John C. Goodman and Cleveland Clinic President Delos M. Cosgrove, April 26, 2007.

- See the Harvard Medical International Web site at http://www.hmi.hms.harvard.edu/about_hmi/overview/index.php.

- “Health Care in Panama,” International Living .

- Milstein and Smith, “Will the Surgical World Become Flat?”

- Corchado and Iliff, “Good Care, Low Prices Lure Patients to Mexico.”

- See Bumrungrad's Web site at http://www.bumrungrad.com/.

- See Planethospital's Web site at http://www.planethospital.com/doctors-and-hospitals/.

- See PlasticSurgeryJourneys.com.

- See http://www.healthmedicaltourism.org.

- See http://www.beautyfromafar.com/.

- This combination of surgeries is sometimes called the “mommy makeover.” See Natasha Singer, “Is the ‘Mom Job' Really Necessary?” New York Times , October 4, 2007.

- Ibid.

- Several anecdotes are posted on PlasticSurgeryJourneys.com.

- See “Consumers Go Abroad in Pursuit of Cost-Effective Healthcare, ” Managed Healthcare Executive, Vol. 16, No. 7, July 2006.

- Roth, “$12 for a Half Day of Massage for Back Pain.”

- Alsever, “Basking on the Beach, or Maybe on the Operating Table.”

- Joseph McMenamin, “Medical Tourism and Legal Liability,” Medical Travel Today, CPR Communications, Vol. 1, No. 1, September 2007.

- For instance, see Tracy Correa, “Traveling Can Help Cure Medical Costs,” Fresno Bee , June 19, 2007.

- Quotes are available online at http://www.aosassurance.com/PublicHtml/index.htm.

- For specific remedies, see Agreement. Available at http://www.aosassurance.bb/PublicHtml/Documents/PMMI/PMMI%20policy%20wording%20(2).pdf. Accessed September 18, 2007.

- Unmesh Kher, “Outsourcing Your Heart,” Time Magazine , May 21, 2006.

- Joyce Howard Price, “Under the Knife Overseas,” Washington Times , December 3, 2006. Also see Kher, “Outsourcing Your Heart.”

- Grant Gross, “Analyst: Outsourcing Can Save Costs in Health Care,” InfoWorld , November 16, 2004.

- For a discussion on telemedicine, see Anthony Charles Norris, Essentials of Telemedicine and Telecare (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 2002).

- For information how telemedicine might impact rural areas, see James Grigsby, Richard Morrissey and Dena S. Puskin (presenters), “Telemedicine in Rural Areas: Research Findings and Issues for States,” Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Conference on Strengthening the Rural Health Infrastructure (Asheville, N.C.), November 19-21, 1997.

- Robert M. Wachter, “The ‘Dis-location' of U.S. Medicine — The Implications of Medical Outsourcing,” New England Journal of Medicine , Vol. 354, No. 7, February 16, 2006. For a layman's view of outsourcing radiology, see Associated Press, “Some U.S. Hospitals Outsourcing Work,” MSNBC.com, December 6, 2004.

- Associated Press, “Some U.S. Hospitals Outsourcing Work,” MSNBC.com, December 6, 2004. Available at www.msnbc.msn.com/id/6621014/. Accessed April 27, 2007. See Nighthawk Radiology Services Web site: http://www.nighthawkrad.net/.

- Robert M. Wachter, “International Teleradiology,” New England Journal of Medicine , Vol. 354, No. 7, February 16, 2006, pages 662-63; Milstein and Smith, “Will the Surgical World Become Flat?”

- “NHS Scans to be Sent Abroad” BBC News, July 9, 2004.

- Conversation with Rudy Rupak, president of PlanetHospital, Spring 2007.

- For instance, see Gina Kolata, “Looking Past Blood Sugar to Survive with Diabetes,” New York Times , August 20, 2007.

- For instance, a doctor and nurse practitioner working as a team were better able to manage chronic conditions than a physician working alone. See David Litaker, “Physician-nurse practitioner teams in chronic disease management: the impact on costs, clinical effectiveness, and patients' perception of care,” Journal of Interprofessional Care , Vol. 17, No. 3, August 2003, pages 223-37.

- Jane Anderson, editor, “Use of Telemedicine Tools Grows within DM,” Disease Management News , Vol. 12, No. 8, 2007.

- For instance, children assigned to interactive disease management for asthma fared better than those in a control group with traditional disease management. See Ren-Long Jan et al., “An Internet-Based Interactive Telemonitoring System for Improving Childhood Asthma Outcomes in Taiwan,” Telemedicine and e-Health , Vol. 13, No. 3, June 2007, pages 257-68.

- Fraser, “Employers Increasingly Tapping Medical Tourism for Cost Savings.”

- Arnold Milstein, Written Testimony to the U.S. Senate, Special Committee on Aging, June 27, 2006.