Telemedicine — the use of information technology for diagnosis, treatment and monitoring of patients' conditions — brings a new dimension to 21st century health care. Entrepreneurs are using the Internet, improvements in computer software and the advent of high-speed telecommunications networks in innovative ways to make medical care more accessible and convenient to patients, to raise quality and to reduce costs.

Patients, physicians and other medical providers all must deal with a wide range of problems in the traditional health care system. For example:

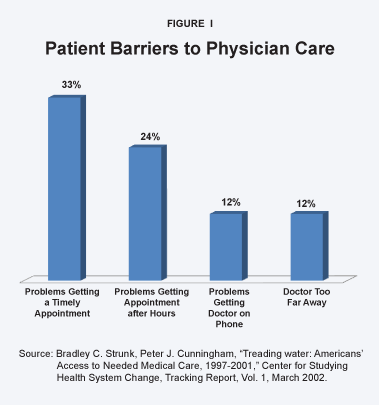

Problem: Doctors are hard to see. As many as one-in-three people have trouble seeing their primary care physician, and nearly one-in-four have problems taking time from work to see a doctor.

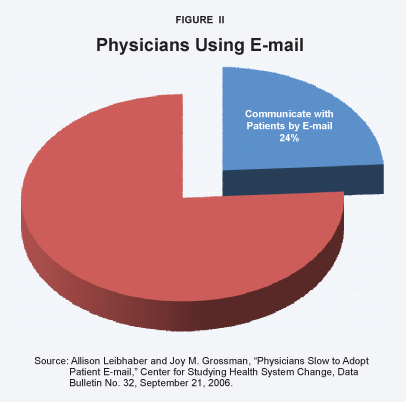

Problem: Patients have trouble contacting physicians by telephone or e-mail. Although lawyers and other professionals routinely consult with their clients by telephone and by e-mail, very few doctors will consult by telephone and less than one-in-four communicates with patients electronically.

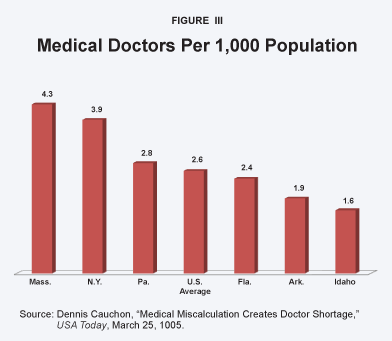

Problem: There are too few doctors in rural areas. Compared to metropolitan areas, there are fewer physicians serving rural patients and patients must travel farther for office visits.

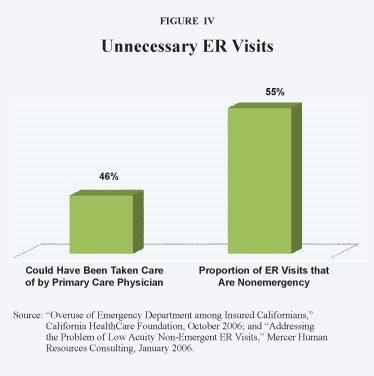

Problem: Patients overuse emergency rooms. Because their primary care physicians are inaccessible by telephone or after hours, many patients turn to hospital emergency rooms. More than one-half of all ER visits are for nonemergency health problems.

Problem: Patients have difficulty getting information during office visits. More than one-third of physicians do not have the time to deliver enough information to their patients during office visits, and 60 percent of patients later say they forgot to ask questions during their visits.

Problem: Fragmented care. Because most patients see a number of physicians over time, care is often fragmented and physicians often must treat patients with inadequate information.

Problem: The chronically ill are not well served. More than 125 million Americans have chronic medical conditions, yet most are not receiving appropriate care, in part because monitoring is complex and expensive.

Telemedicine has the potential for restructuring medical care in ways that can solve many of these problems, while reducing costs and improving the quality of care.

Solution: Nontraditional physician practices. To avoid the time and expense of traditional office visits, medical entrepreneurs are creating innovative services for patients. These include practices that are staffed by physicians who are available after regular office hours, are easier to reach and are able to order tests, initiate therapies or treatments and prescribe drugs.

Solution: Pay doctors for e-mail and telephone consultations. Entrepreneurial providers are creating services outside the third-party payment system that allow patients to pay directly for access to physicians or nurses by telephone or e-mail. In some cases, insurers are reimbursing for e-mail and telephone consultations in addition to office visits.

Solution: Empower rural consumers to direct spending on their own health care. If Medicare and Medicaid allowed beneficiaries to control some of the dollars spent on their health care, entrepreneurial providers would offer services that are not now available. For example, retail medical clinics staffed by nurse practitioners is one possibility; consultations by phone with medical specialists is another.

Solution: Physician advisory services can substitute for emergency room care. In many cases merely speaking to a doctor by phone avoids an unnecessary ER visit. Medical entrepreneurs are setting up 24-hour consultation services across the country to which individuals can subscribe, and an increasing number of insurers cover the cost of such services.

Solution: Internet-based medical information. Patients no longer have to rely on their doctor for answers to every question. Medical information has become available outside doctors' offices through thousands of health-related Web sites on the Internet. According to a recent poll, more than 80 percent of Americans with Internet access — about 113 million adults — have searched online for health information.

Solution: Electronic medical records. The use of electronic medical records (EMRs) — containing a patient's medical history, test results and prescription information — has the potential to improve quality and reduce medical errors while allowing for better coordination of patient care among different providers.

Solution: Remote chronic disease management. Programs to manage chronic medical conditions are beginning to use remote monitoring. These involve training patients to collect and transmit data on their condition and allowing them to receive physician feedback. Research has shown such monitoring not only can improve patients' adherence to protocols, it also can often be outsourced to low-cost, qualified medical providers in developing countries.

Obstacles. The obstacles to achieving the full potential of telemedicine include the way in which Americans pay for health care, the medical culture in which physicians practice and government regulation of medical practices. For instance:

- Because patients pay directly for only 13 cents of each dollar spent on health care, providers have little incentive to create innovative patient-pleasing services unless third parties (private insurers, employers and government) pay for them.

- The medical culture generally, and medical societies in particular, have tended to oppose expanding patient services beyond traditional face-to-face office consultations and treatment in traditional settings (clinics and hospitals).

- State laws and regulations that prevent physicians licensed in one state from practicing in other states also keep doctors from providing medical care across state lines — such as writing a prescription or providing follow-up consultations remotely to patients who have returned home to another state.

Overcoming the Obstacles. These barriers must be lowered to realize the full benefits of telemedicine. If patients control more of their health care dollars, entrepreneurs will design innovative services to meet their needs. If medical entrepreneurs are allowed to employ physicians in other states and overseas, they can reduce the cost of services. If outdated state regulations restricting the practice of medicine are reformed, the quality of care can be improved.

[page]Recent advances in information technology — the hardware and software systems used to record, store, process and transmit data — have created new opportunities for patients and doctors to interact in ways that were impractical only a few years ago. The use of information technology to diagnose, treat and monitor patients' medical conditions remotely is called telemedicine . Since the late 1990s, the growth of the Internet, improvements in computer software and the advent of high-speed telecommunications networks have led to a rapid increase in telemedicine. Health care entrepreneurs are using these opportunities to make medical care more accessible and convenient to patients, to raise quality and to reduce costs.

“Patients seeking physician care face barriers.”

This study examines how telemedicine and other information technology are contributing innovative solutions to some of the problems patients and health care providers encounter under the traditional model of health care delivery. It also examines some of the obstacles to progress and the public policy changes needed to remove them.

[page]Many patients have difficulty finding a physician, obtaining an appointment and taking time from work for a traditional office visit. It is even more difficult to reach a physician by telephone or e-mail, or after office hours. Some patients are unaware of local urgent-care or after-hours clinics. They don't know what to do about sudden medical problems — including how to reach a doctor or nurse by phone. 1 Often, the only way to reach a physician after hours is in a hospital emergency room — which is both costly and time consuming. Access to medical care outside of the traditional office setting is particularly important — and particularly difficult — for patients with multiple chronic medical problems.

“Doctors are difficult to reach outside their offices.”

Problem: Doctors are hard to see. A study of medical access between 1997 and 2001 found that seeing a doctor is becoming increasingly difficult:

- The proportion of people reporting problems seeing their primary care physician rose from less than one-quarter (23 percent) to one-third over the four-year period.

- Nearly one-quarter reported problems taking time from work to see a physician. 2 [See Figure I.]

Problem: Patients have trouble contacting physicians by telephone or e-mail. Doctors are difficult to contact outside the office. Lawyers and other professionals routinely communicate with their clients by telephone and e-mail; very few doctors will consult by telephone and less than one-in-four communicates with patients electronically. 3 [See Figure II.] A Harris Interactive poll shows that most patients with Internet access (90 percent) would like the ability to consult their physician online. 4 But for a routine prescription or answer to even the simplest medical question, patients must usually make an office visit. 5

Why do doctors avoid telephone and e-mail consultations? The simple answer: Insurers generally do not reimburse them for phone or e-mail consultations. 6

While phone calls to or from a family physician's office are relatively common, they tend to be for scheduling appointments or receiving lab test results from an earlier visit. Often, the patient does not even speak with the physician; instead, a nurse or office manager relays information.

“Most doctors do not use telephones or e-mail to communicate with patients.”

Prescription refills . When patients attempt to refill a prescription, they sometimes discover the pharmacy will not refill the medication without permission from the prescribing physician. Generally the pharmacist (or pharmacy tech) calls the physician's office, and a nurse in turn consults with the physician. When this occurs, the doctor may require an inconvenient and costly office visit before renewing the prescription.

On-call physicians. When physicians are out of town or need a break from after-hours phone calls from patients, they often arrange with colleagues to cover for each other. The on-call physician may not have any relationship with his colleague's patients. And covering physicians rarely have access to patients' medical records when they answer a call. Yet medical societies approve of the practice because often the only alternative is a local hospital emergency room.

“Rural areas have fewer physicians.”

Problem: There are too few doctors in rural areas. Compared to metropolitan areas, there are fewer physicians serving rural patients and patients must travel farther for office visits. More than 35 million Americans live in areas underserved by physicians, according to government estimates. The American Medical Association estimates that 16,000 more doctors are needed to fill the gap. 7 Although there are 2.6 physicians per 1,000 residents in the United States, they are not distributed equally among the states. For example [see Figure III]:

- Massachusetts has 4.3 doctors per 1,000 residents.

- At 2.4 per 1,000 residents, Florida is close to the U.S. average for physicians per capita. 8

- Idaho has only 1.6 physicians per 1,000 residents.

“A majority of emergency room visits are for nonemergencies.”

However, these averages mask wide variations in the number of physicians within states. For example, in California, the counties of Glenn, Modoc and Yuba have fewer than one physician (0.78) per 1,000 residents. By contrast, the wealthy suburban counties around San Francisco Bay have about three times as many per thousand (2.33). 9

Rural patients must often travel long distances to see a primary care physician. They have even more problems finding specialists.

Problem: Patients overuse emergency rooms. Fifty-five percent of the 114 million visits to hospital emergency rooms in a given year are for nonemergencies. 10 Even patients judged their conditions as nonurgent. A 2006 survey of California hospitals found that nearly half of ER patients thought they could have resolved their medical problem with a visit to their doctor, but they were unable to obtain timely access to care. 11 [See Figure IV.] Patients who seek nonurgent care in the hospital emergency room waste significant resources because the ER is one of the most costly ways to obtain routine treatments. 12

Overall, the total cost of unnecessary physician office visits and unnecessary emergency room visits is just under $31 billion annually, or about $300 per American household per year. 13

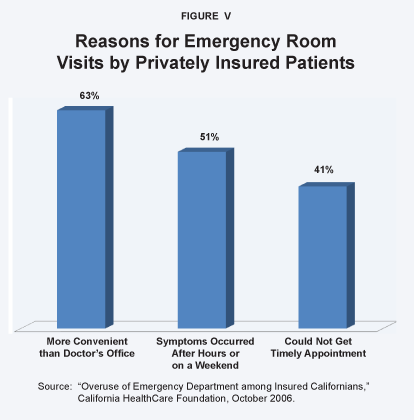

Why do people with health coverage visit an emergency room for nonurgent care? Because they cannot easily obtain care from their primary physician outside office hours. According to the 2006 California survey of recent emergency room patients:

- Seventy-one percent of Medicaid enrollees and 63 percent of privately insured visitors claimed seeking Emergency Room care was more convenient than seeking care from their doctor.

- More than half of both groups experienced symptoms after normal office hours or on a weekend, when their physician was not available.

- Nearly half of patients who visited an ER said they could not get a timely doctor's appointment. [See Figure V.]

“Insured emergency room patients say the ER is more convenient.”

Problem: Patients have difficulty getting information during office visits. The average time physicians spend with individual patients has not fallen significantly, but the amount of information physicians need to convey to patients during an office visit has grown. This includes discussing prevention, potential medical treatments, possible drug interactions, safety warnings and so forth. The proportion of physicians saying they do not have enough time to spend with patients rose nearly 24 percent between 1997 and 2001, from 28 percent to 34 percent of doctors surveyed. 14

According to a recent article in the Journal of the American Medical Association , patients usually want more information about their medical condition than they receive from their doctors. For instance:

- During a 20-minute office visit, physicians spend less than one minute planning treatment, on the average.

- Doctors discuss options and help patients arrive at a treatment based on their preferences during fewer than one in 10 office visits.

- About half the time, doctors fail to ask patients whether they have questions. 15

“Most patients agree medical errors are preventable.”

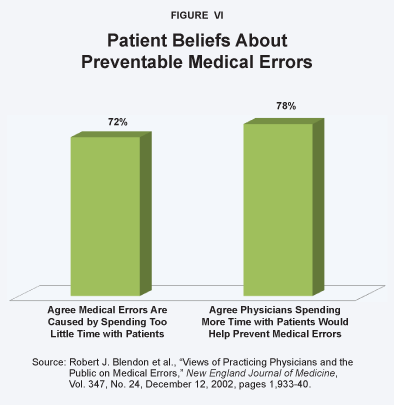

A Harris Poll found that even when physicians offer to answer patients' questions, 60 percent of patients forget some of the questions they meant to ask. 16 Moreover, patients retain only a fraction of the information they receive from their physician during an office visit. 17 Patients perceive that this lack of communication negatively affects the quality of patient care. For instance, more than two-thirds of the public (72 percent) think “insufficient time spent by doctors with patients” is one cause of preventable medical errors, and three-fourths (78 percent) think that the occurrence of medical errors could be reduced if physicians spent more time with patients. 18 [See Figure VI.]

Problem: Fragmented care. P atient medical records are often handwritten and are usually maintained and stored separately by each physician, clinic or hospital they use. Consequently, conditions affecting the patient may be unknown at the time of treatment. Because most patients see a number of physicians over time, care is fragmented, and doctors and other medical providers often must treat a patient with limited information. This lack of care coordination often leads to medical errors, adverse drug events and redundant medical tests. 19

Problem: Treating the chronically ill is especially difficult. The estimated cost of chronic diseases in the United States, including treatment and lost productivity, is $1.3 trillion per year. 20 Unless this trend is reversed, by 2023 the cost will swell to $4.2 trillion.

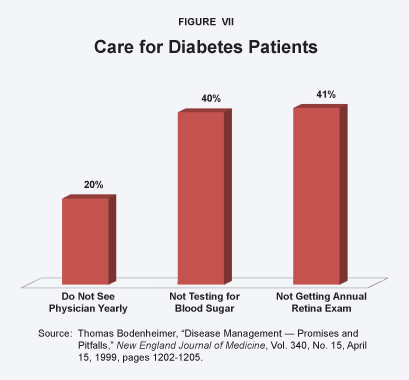

More than 125 million Americans have chronic medical conditions. 21 Most are not receiving appropriate care from their physicians. 22 For instance, less than one-quarter of patients with high blood pressure control it adequately. Twenty percent of Type-1 diabetic patients do not see a doctor annually. Twice that number do not test their blood sugar level regularly, and 40 percent do not receive recommended yearly retinal examinations. 23 [See Figure VII.] One reason for this poor compliance with recommended care is that physicians often lack an integrated system to monitor their patients' chronic conditions. 24

“Many patients with chronic illnesses get inadequate care.”

Helping patients properly manage a chronic condition — especially diabetes, which often results in complications such as heart disease — is often complex and time-consuming. 25 In fact, millions of people have multiple chronic conditions. When multiple physicians are treating a patient for multiple conditions, a case manager must ensure that they are coordinating their efforts. However, such close monitoring and interaction is labor-intensive and costly. Insurers rarely reimburse these management tasks, or reimburse them at rates lower than the cost of providing the services.

Information technology has the potential for restructuring medical care in ways that can solve many of these problems, often while reducing costs and improving quality of care. The practice of telemedicine is relatively new, and still developing rapidly. Already, numerous studies point to the benefits of using telecommunications and other information technologies in innovative ways to care for patients.

Solution: Nontraditional physician practices. Many medical conditions and testing procedures do not require the physical presence of a physician or the time and expense of an office visit. To meet this demand, entrepreneurs are creating nontraditional medical services in which clinical care is available in more convenient locations, by telephone or through virtual offices on the Internet. They are staffed by physicians who will order tests, initiate therapies or treatments and prescribe drugs. For instance, many medical providers are beginning to integrate convenient Web-based services into their practices. Solantic is a small Florida-based chain of free-standing, walk-in urgent care clinics. 26 Patients can register online and fill out their medical history prior to arriving at the clinic. They can also sign up online for X-rays or lab tests without a doctor's office visit. 27 These clinics are open extended hours and on weekends. Competition from these new clinics may lead traditional physician practices to offer more convenient weekend and extended hours. 28

“Some physicians are available after hours and by telephone or e-mail.”

Some innovative physicians are becoming more flexible, providing patients with the services they need in a timely manner. These may include after hours office visits or even house calls. Or they might involve phone calls or e-mail, as shown by the following case studies.

Case Study: Flexible Physician Practices . Docto k r Family Medicine is the Virginia medical practice of Dr. Alan Dappen, who practices medicine mostly by telephone and e-mail contact. Patients can schedule an appointment or e-mail the doctor, all from the Docto k r.com Web site. In fact, Dr. Dappen's waiting room is a Web page.

Patients can also make appointments to be examined by Dr. Dappen in his office, and though he will even make house calls for some patients, he encourages most patients to consult with him by e-mail or telephone.

Dr. Dappen bases his consultation fees on the amount of time required. Charges are billed in five-minute increments and range from $25.50 for in-office visits to $17 for phone consultations with patients who have set up prepaid accounts. A simple call to renew a prescription or ask questions generally costs less than $20. The office will help with insurance billing and also takes PayPal. Patient records are kept electronically.

Case Study: Low-cost “concierge medicine” in Dallas. Concierge medicine is normally associated with personalized services for the wealthy. As noted above, these services can be expensive. However, in Collin County, Texas, a Dallas suburb, physician Nelson Simmons offers a version of that service for less than $500 a year.

About 70 small business owners pay $40 per employee per month for Simmons' plan. In return, employees get same-day primary care services and steep discounts on diagnostic tests and specialist care. Enrollees must pay out-of-pocket for specialist care, surgeries and diagnostic tests. But Simmons negotiates the rates, which are typically much lower than what others pay. For example, a tonsillectomy for a child costs less than half of the normal fee ($2,100 versus $4,800) and an MRI scan can be less than one-fourth of the standard charge ($350 versus $1,600). 29

Solution: Pay doctors for e-mail and telephone consultations. E-mail is a convenient and efficient way to consult with a physician. One recent study found that an electronic messaging system similar to e-mail reduced physician office visits and associated laboratory costs. When health plan members were able to e-mail their doctor, office visits and laboratory costs were approximately $22 less per member per year compared to those who lacked this service. 30 Kaiser Permanente also found that an electronic messaging system reduced office visits. 31

“Using e-mail reduces office visits.”

Greater reliance on e-mail and phone consultations would reduce physicians' need for office space, including exam rooms and waiting areas. One study found that it cost a dermatology practice $274 per hour to provide consultations by telephone to patients on Nantucket Island, compared to costs of $346 an hour for an office-based dermatology practice in Boston. 32 Patients share in the benefits from the elimination of office visits through lower fees, less waiting time and lower transportation costs.

A patient's medical condition may not require the physical presence of a physician or the time and expense of an office visit. A recent study found most patients willing to pay about $25 for the convenience of a “televisit” over an in-office visit. 33 To meet this demand, entrepreneurs are creating medical services staffed by physicians who will order tests, initiate therapies or treatments and prescribe drugs.

E-mail consultations . In 2000, First Health Group became one of the first major health insurers to reimburse physicians for medical consultations over the Internet. First Health agreed to pay $25 for each e-mail exchange between patients and doctors to encourage physicians to interact more frequently with chronically ill enrollees. The program's goal was to reduce inpatient hospitalizations that often result when symptoms are ignored. 34

Other insurers are experimenting with online consultations. In the Northeast, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center receives $30 for each online consultation from Anthem Blue Cross, Cigna and Harvard Pilgrim. BlueCross and BlueShield is starting such services in a number of states, paying from $24 to $30 for each e-mail consultation. Kaiser Permanente has also experimented with secure messaging between plan members and physicians.

Physicians who exchange e-mail with their patients find it often replaces rambling telephone conversations, since e-mail patients tend to spend more time composing their thoughts and creating focused messages. 35 Kaiser Permanente found that allowing enrollees to e-mail questions to their doctor through a secure messaging system called KP HealthConnect was associated with a 7 percent to 10 percent reduction in primary care visits. 36

“TelaDoc provides physician care by telephone at any time nationwide.”

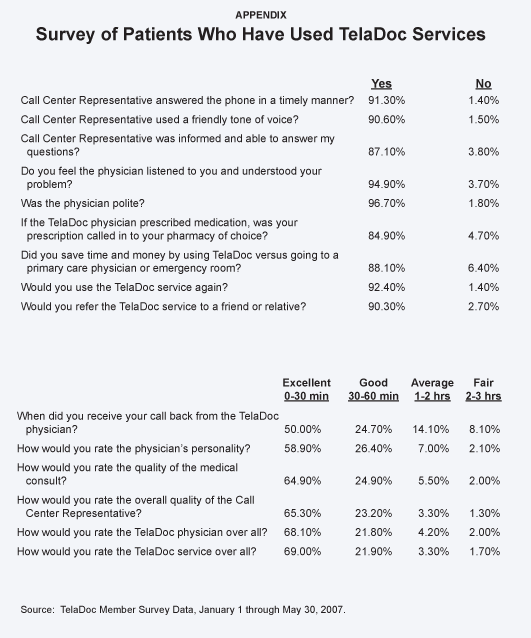

Case Study: Convenient care by TelaDoc . TelaDoc Medical Services, located in Dallas, is a phone-based medical consultation service that works with physicians and health plans across the country. For instance, a traveling business executive who develops a rash or comes down with a sore throat can obtain less expensive and time-consuming treatment by making one phone call, rather than visiting an emergency room or expensive urgent care center. 37 Individual enrollees pay $35 for each consultation, which are available around the clock (compared to an emergency room visit costing an average of $383). 38 Eighty-eight percent of those who used TelaDoc reported they saved time and money compared to a traditional office visit or a trip to the emergency room.

When a member signs up for the service, his or her medical records are digitized and placed online so a consulting physician can access them from anywhere in the country. The member needs only a telephone to use the service.

For instance, when a member places a call to TelaDoc's call center to request a consultation, the system notifies several participating physicians, licensed in the state where the call originates, that a patient is waiting. The first physician who returns the call receives a $25 consultation fee, while TelaDoc retains $10. TelaDoc guarantees a call will be returned within three hours or the consultation is free. Customer surveys have found that most calls are returned within 30 to 40 minutes. 39 TelaDoc results have been positive:

- A physician returns a patient's phone call within 30 minutes (or less) 50 percent of the time.

- Seventy-five percent of the calls are returned within one hour.

- Less than 11 percent of consultation requests required patients to wait more than two hours for a return call. 40

This unique service has proven to be quite popular — TelaDoc enrolled its one-millionth member in the fall of 2007. Member experiences and satisfaction with the service are closely monitored through surveys. Participants are offered a financial incentive ($3 off the cost of the next consultation) to fill out a survey. Customer satisfaction is high [see the Appendix]: 41

- Nearly 93 percent of those who have used the service report they would use it again.

- Just over 90 percent would recommend it to a friend or family member.

- Members reported nearly identical satisfaction with their consulting physician.

- More than 90 percent of respondents reported they would rate the overall TelaDoc experience as either “excellent” or “good.” 42

Patients who see their primary care physician for an in-office visit often feel that they've been rushed or that their doctor doesn't listen to them. 43 But 95 percent of TelaDoc callers report they felt the physician listened to them and understood their problem. 44

The TelaDoc service is designed for patients who cannot access their primary care physician in a timely manner, or when those patients (or their doctors) are out of town. It is not intended to replace primary care providers. The most common conditions that patients call about are infections (respiratory and urinary tract), allergies, pain (skeletal, muscle and arthritic), minor joint trauma (sprains and strains) and gastroenteritis.

“TelaDoc physicians have access to patients' electronic medical records.”

Physician qualifications are also high — all but one of TelaDoc's participating physicians are U.S. board-certified in a medical specialty. Further, unlike most physician practices, TelaDoc stores patient records electronically. The physician can access the patient's medical history online, e-mail a prescription to a pharmacy and add information to the patient's electronic medical record. The use of these technologies improves care coordination and prevents adverse drug interactions.

Solution: Patient-directed health care to increase access in rural areas . The field of telemedicine began more than 40 years ago as an attempt to deliver clinical services to geographically isolated patients. Of particular interest was the need to provide people living in remote rural locations with access specialists. 45 One study conducted in a remote area of Australia found that providing remote medical consultations by satellite increased aborigines' access to medical care, improved health status and reduced costs. As a result of telemedicine, patients and specialists were flown in (and out) for consultations less often. There also were fewer emergency evacuations for medical reasons. 46

If Medicare and Medicaid allowed beneficiaries to control some of the dollars spent on their health care, entrepreneurial providers would offer services that are not now available. These might include retail medical clinics staffed by nurse practitioners, or consultations by phone with medical specialists.

“Physician or nurse call lines provide advice.”

Solution: Physician advisory services. Many health insurance policies (and employer health plans) include access to medical call lines to assist enrollees with information about simple health needs. Because patients often find it difficult to contact their regular physician by telephone after office hours, the firm Doctor On Call has taken the concept of a nurse call line one step farther. It provides individual subscribers (and health plan members) immediate telephone access to physicians. 47 Doctor On Call's licensed physicians answer questions about diseases and conditions and provide medical advice. However, its physicians cannot initiate treatments, order tests or prescribe medications. In other words, these physicians do not practice medicine over the phone. Rather, discussions are for informational purposes only and are not considered “medical treatments.”

With few options, people searching for peace of mind or reassurance (such as mothers of sick children) often turn to emergency rooms. Doctor on Call believes that in many cases merely speaking to a doctor by phone avoids an unnecessary ER visit.

Sometimes patients may avoid an unnecessary ER visit merely by speaking with a nurse on the phone. McKesson's ASK-A-NURSE® program works with health care organizations to offer health information services to employer groups, specific target populations or members of a community. The service can provide either limited or 24 hour-per-day access to nurses. 48 Another service, FoneMed, provides health plans with call centers staffed by nurses who use software-based medical protocols to answer patient questions and perform triage — that is, direct patients to the proper provider. 49

Nurse call lines also can provide impartial health information and wellness coaching in addition to chronic disease management. For instance, the firm CareNet hires registered nurses, dieticians and other health professionals as health coaches to help health plan enrollees make lifestyle improvements (such as exercise and diet) and set and achieve specific health goals, such as losing weight, lowering cholesterol, or controlling diabetes, hypertension and so forth. CareNet also offers care coordination, remote monitoring and a one-on-one relationship with a personal nurse to health plan enrollees who have chronic conditions. 50

Solution: Internet-based medical information. Patients no longer have to rely on their doctor for answers to every question. Medical information has become available outside doctors' offices through thousands of health-related Web sites on the Internet. The vast amount of knowledge available on the Internet has led to dramatic changes in how people obtain information about health and medicine. 51 Frequently, instead of visiting a physician's office for answers to their medical questions, people can search the Internet (keeping in mind that not every medical Web site is reliable). Estimates vary, but by most accounts there are approximately 20,000 health-related Web sites. 52 According to a recent poll, more than 80 percent of Americans with Internet access — about 113 million adults — have searched online for health information. 53

Solution: Electronic medical records. The use of electronic medical records (EMRs) — each containing an individual patient's medical history, test results and prescription information — has the potential to improve quality and reduce costs. 54

Only a small percentage of hospitals and physicians currently utilize EMRs, but a growing number of health care providers and independent services offer patients the ability to store and manage their own EMRs securely online, so that they are accessible to the individual patient and any physician the patient chooses.

“Electronic medical records controlled by patients and accessible to physicians can reduce medical errors.”

Because most patients see a number of physicians over time, remotely accessible medical histories will allow better coordination of care among different providers. In fact, EMRs are essential for a rapidly expanding area of telemedicine — the remote monitoring of patients with chronic diseases (see discussion below). 55 In fact, telemedicine may become the preferred way for doctors to monitor the infirm and manage patients' chronic conditions. Furthermore, remote access to EMRs by physicians makes telephone or e-mail consultations with patients more useful — and the ability of multiple health care providers to view and add to a case history facilitates collaboration among primary care physicians, nurses and specialists.

EMRs can improve quality by reducing errors. Policymakers have made replacing handwritten prescriptions with electronic prescriptions a national health care goal. Handwritten prescriptions are a major source of medical errors — causing nearly 200,000 adverse drug events in hospitals each year. 56

“Remote monitoring can improve care for chronically ill patients.”

Microsoft recently rolled out an online personal health record management service, called HealthVault , designed to make it easy for individuals to store personal health information securely on the Internet, to control access to their information by health care providers and to ensure the accuracy of data. A person's health history is password-protected; any attempt to access the records is recorded; any additions, deletions or edits are tracked. Microsoft expects technology companies to design products that work with the service. Take blood glucose monitors, for example. These meters could connect wirelessly to a patient's computer (using BlueTooth technology) and transfer data to a permanent health record like HealthVault.

Solution : Remote monitoring for chronic disease management. Traditional disease management programs for patients with chronic conditions generally involve multiple providers responsible for separate aspects of health care. A team of medical providers working together can improve outcomes for patients with chronic conditions by aggressively managing all aspects of medical treatment. 57 Unfortunately, this type of close supervision is labor-intensive and costly. Instead, disease management programs are beginning to use telemedicine. 58

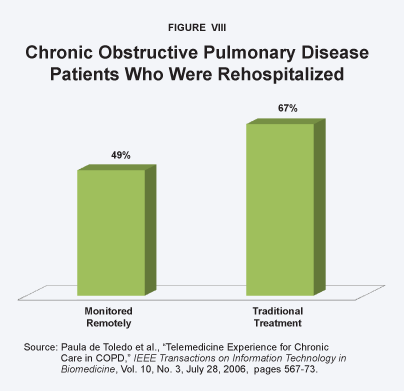

Research has shown that telemedicine can improve adherence to protocols and increase convenience for patients with chronic ailments. 59 For example, for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), researchers determined that telemedicine lowered readmission rates. Patients were trained in the use of an inhaler for drug therapy (to improve lung function) and the use of a spirometer to monitor airflow to and from their lungs. Of those monitored from home, only 49 percent were subsequently readmitted to a hospital compared to 67 percent of COPD patients who were not monitored remotely. 60 [See Figure VIII.]  A similar study of remote monitoring of congestive heart failure patients found that over six months the group monitored from home required only half as many rehospitalizations as the control group. 61

A similar study of remote monitoring of congestive heart failure patients found that over six months the group monitored from home required only half as many rehospitalizations as the control group. 61

Telemedicine has also been found to benefit patients with asthma. Patients in a study of remote monitoring experienced fewer asthma symptoms and improved measures of peak airflow into their lungs. An added benefit was improved asthma self-management skills and better quality of life. 62 Likewise, a study of diabetes care found that patients monitored electronically had better controlled blood glucose than those in conventional care. 63 The effect was especially pronounced among diabetes patients with poorly controlled blood glucose levels prior to the study.

“Some medical tasks can be outsourced to qualified physicians in other countries.”

The high cost of disease management may also be reduced by outsourcing some tasks to medical personnel in developing countries. American health care providers could collaborate with qualified low-cost providers overseas who could perform labor-intensive tasks that do not require the physical presence of a physician. 64 In fact, American hospitals are increasingly using radiologists in India and other countries to read X-rays after hours. 65 NightHawk Radiology Services contracts with American-board-certified physicians living in Australia for overnight interpretations of X-rays and scans. This reduces the turnaround time for diagnoses, since these radiologists are available when it is night in the United States. 66 Indian radiologists working from Bangalore, India, can interpret ultrasounds, CT scans and MRIs like an American radiologist working in the United States. 67 Increasingly, information technology will make distance irrelevant and medical personnel will be able to provide medical services regardless of their location.

[page]Although telemedicine has the potential to lower costs and increase competition in many areas of health care, it faces numerous obstacles, primarily because it represents a new and different dimension in health care. Some of these barriers are related to the preponderance of payment for health care by third parties. Some arise from the efforts of entrenched interest groups, including those who do not want to compete with low-cost providers. Federal and state licensing laws and regulations create even more obstacles.

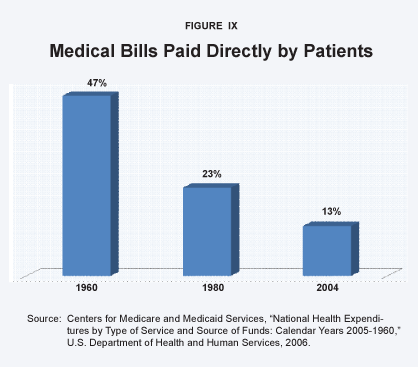

Obstacle: Third-party payment. The primary reason why doctors and hospitals do not communicate with patients electronically is that patients rarely pay their own health care bills. 68 Because patients pay directly out of pocket for only 13 cents of each dollar's worth of health care, providers have little incentive to create innovative patient-pleasing services unless third parties (private insurers, employers and government) will pay for them. 69 Figure IX shows that the proportion of health care paid directly by consumers has been falling for decades: 70

- In 1960, consumers paid about 47 percent of overall health care costs out of pocket.

- The proportion had fallen to 23 percent by 1980.

- For every dollar spent on health care in 2004, consumers paid only 13 cents out of their own pockets.

Obstacle: Medical culture. Throughout its relatively brief history, telemedicine has been primarily envisioned as a way to care for patients in remote areas underserved by physicians and specialists. 71 Historically, the preferred way to care for patients has been the face-to-face consultation. 72 This may explain why the American Medical Association (AMA) came out against prescribing medication over the Internet prior to a physical examination. 73

“Providers have little incentive to create patient-pleasing services because they do not compete for patients on the basis of price.” Medical societies have considerable power to slow or block innovation through their influence over state medical boards. 74 State medical boards, medical societies and other physician groups often discourage certain practices they consider unorthodox by declaring them unethical. 75 Or they imply that quality may be compromised. 76 In some cases, they have gone so far as to make selected practices subject to sanctions, such as denial of hospital privileges and even the loss of the license to practice medicine. 77

Obstacle: State licensing laws. States license and regulate physicians with the ostensible goal of maintaining the quality of medical care. 78 Unfortunately, outdated state licensing laws do not conform to the information age. 79 Recent advances in technology allow a radiologist to read X-rays from India just as easily as an American radiologist. However, the practice of medicine is regulated by state medical boards, which generally require a physician to be licensed in the state where the patient receives treatment. Thus, state licensing laws prevent medical tasks from being performed by providers living in other states or abroad. Foreign physicians also lack the authority to order certain tests, initiate therapies and prescribe drugs that American pharmacies can legally dispense.

Some restrictions on the practice of medicine have been removed in recent years, but many still exist. For example:

- In some states it is illegal for a physician to prescribe medication to a patient online without an initial face-to-face consultation. 80

- It is also illegal in most states for a physician who has examined a patient visiting from another state to provide follow-up treatment via the Internet after the patient returns home.

- It is illegal for a physician to consult by phone with patients residing in a state other than where the physician is licensed.

These laws make it difficult for American patients to seek care from doctors in other states or abroad via telephone or the Internet, and for doctors to employ foreign physicians (which could greatly reduce costs).

“Federal and state laws prevent more efficient delivery of medical care.”

State and Federal Laws Inhibit Beneficial Collaboration. A U.S. physician practice could easily provide doctor visits in a traditional office, coupled with chronic disease management services from a foreign doctor (by telephone or e-mail) and tests done at a convenient retail clinic, when needed. Yet this service could run afoul of the so-called Stark laws. The federal Stark laws make it illegal for a physician to refer a patient for treatment to a clinic in which the doctor has a financial interest. Nor may a physician reward providers who refer patients to him or to a hospital in which he has a financial interest.

Many states have similar laws on their books. Unfortunately, laws meant to prevent self-dealing and kickbacks also inhibit beneficial collaborationbetween doctors and hospitals. For instance, the Stark laws could prevent a physician practice from referring a patient with a chronic condition to an affiliated disease management program (employing a foreign doctor) or prevent it from referring a patient needing minor treatment to an affiliated walk-in clinic.

By limiting compensation arrangements for referrals and collaboration, the Stark laws tend to result in rigid physician group practices that are not particularly convenient or economical for patients.

States Restrict the Employment of Doctors. About one-third of the states have laws banning the “corporate practice of medicine,” which prevent corporations from hiring physicians to practice on their behalf. 81 The implication is that a corporate employer might exert undue pressure to skimp on quality in order to increase or preserve profits. These laws ostensibly aim to ensure the quality of medical care, but in practice they inhibit innovative service arrangements. 82 For example, in many states a company may not establish a chronic disease management service and hire physicians to monitor clients.

One-third of the states have passed laws allowing some firms (such as hospitals and health plans) to hire physicians directly to practice on their behalf. In the rest of the states, the laws are either unclear or appear to support or restrict the practice to varying degrees.

[page]As the previous section indicates, the greatest barriers to innovation and competition in health care are government laws and regulations . Evidence suggests that where markets are competitive, entrepreneurial providers create innovative services. 83 Deregulating health care and equalizing the tax treatment of self-insurance and third-party insurance are important steps in the right direction.

Needed Reform: Remove tax penalties on self-insurance . Traditionally, tax law has favored third-party insurance over individual self-insurance. Every dollar an employer pays toward employee health insurance premiums avoids income and payroll taxes. For a middle-income employee, this generous tax subsidy means government is effectively paying for almost half the cost of health insurance. On the other hand, until recently, the government taxed almost half of every dollar employers put into savings accounts from which employees could pay their medical expenses directly. The result was a tax law that lavishly subsidized third-party insurance and severely penalized individual self-insurance. This encourages the use of third parties to pay every medical bill, even though it often makes more sense for consumers to manage discretionary expenses themselves. 84

“Tax law should treat Health Savings Account deposits the same as third-party insurance premiums.”

If the tax laws made it easier for people to self-insure instead of relying on third-party payers, competition would improve the efficiency of the medical marketplace. Currently, Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) are allowing millions of people to partly self-insure. However, congressional tax-writing committees have made decisions about the design of HSAs that more properly should be made by the market. 85 For instance, the amount of the HSA deposit and the accompanying health insurance deductible are set by law. Instead, the market should be allowed to answer such questions as: What is the appropriate deductible for each service? Should different amounts be allowed for the accounts of the chronically ill? In finding answers, markets are smarter than any individual, because they benefit from the best thinking of everyone. Further, as medical science and technology advance, the best answer today may not be the best answer tomorrow.

Needed Reform: Greater patient autonomy. The first step is for state and federal policymakers to understand that telemedicine will benefit American consumers by reducing costs and improving quality through greater access to medical information and care. 86 Just as information technology has improved productivity in virtually every other area of the economy, it will also improve the productivity of medical care. Physicians' groups should understand that telemedicine also stands to benefit providers — who should not be limited to treating patients in the office (or hospital). Reforms should prevent state medical societies from blocking innovative changes they fear or dislike. Public policy should allow patients themselves to decide which innovative services hold value and which ones do not.

Needed Reform: Modernize state licensing laws. Preliminary research suggests that telemedicine is not only convenient, it also saves money on unnecessary office visits and reduces emergency room visits. Moreover, patient satisfaction among those who talk to a physician by telephone is high. However, outdated licensing laws reduce the cost saving potential of telemedicine. Some experts favor a voluntary regional approach to licensing laws by local jurisdictions instead of a nationwide reform instituted by the federal government. 87

“Qualified foreign physicians should be allowed to provide telemedicine services.”

However, medical licensing laws must be brought into the information age, where distance (or country) is irrelevant. 88 Reforms should include recognizing providers in other countries as alternative resources. For instance, many Indian and Thai physicians are board-certified or licensed in the United States, Australia, Britain or Canada. Foreign physicians who meet international standards should be allowed to provide telemedicine services to U.S. citizens if they have been approved for a U.S. hospital staff or included in a U.S. insurer's health plan. It does not make sense in the 21st century for each state to approve and police physicians living thousands of miles away. The same holds true for physicians practicing in the United States. Laws that prevent physicians in one state from consulting with patients in other states by telephone or e-mail should also be eased.

Relax Laws that Inhibit Beneficial Collaboration. The federal Stark laws prohibiting self-referral should be modified to allow innovative, efficient arrangements for coordination and provision of care. The Stark laws make it difficult to integrate the services of physicians living abroad into the practices of local providers. Integrated medical services would allow domestic providers to compete by creating more efficient operations. For example, a traditional physician practice could offer disease management for chronic conditions at a lower cost through an associated Indian physician. An American radiology practice could hire a lower-cost Indian radiologist to read X-rays overnight.

Relax Laws Prohibiting the Corporate Practice of Medicine. This would allow a health insurer to hire licensed physicians to help plan members suffering from chronic diseases better manage their conditions. 89 It would also allow a U.S. technology company to hire qualified doctors and nurses from other countries to consult with American patients by phone (or e-mail). Corporate ownership also has the advantage of better access to capital markets, economies of scale and the ability to integrate the expertise of other professionals (such as industrial engineers).

Ownership is not so restricted in other industries where very low error rates are required for consumer safety. The airline industry provides a strong example: If airlines were prevented from hiring pilots and owning airplanes, the industry would likely be very different. Rather than numerous carriers flying thousands of large airliners on thousands of regularly scheduled routes, the industry would likely be dominated by charter pilots flying small propeller-driven planes.

“Corporations should be allowed to hire physicians.”

Corporate ownership of airlines has not reduced safety. In fact, the health care industry is increasingly looking to the airline industry's quality improvement procedures for insight into ways to improve patient safety. 90 For instance, flight crews receive training designed to break down hierarchy and empower all crew members to speak up if they feel safety is compromised. By comparison, many experts think the lack of communication among surgical staff in operating rooms leads to preventable medical errors. 91

[page]Telemedicine provides important new opportunities to improve health care in the 21st century. Telemedicine is safe, efficient and convenient for both patients and providers. It is often the method preferred by patients who demand timely access to their doctors. And it is a method endorsed by a growing number of doctors who understand its potential. Other industries have taken advantage of information technology to benefit consumers in numerous ways. It is time that health care does the same.

NOTE: Nothing written here should be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of the National Center for Policy Analysis or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before Congress.

[page]- Overuse of Emergency Department among Insured Californians,” California HealthCare Foundation, October 2006.

- Bradley C. Strunk and Peter J. Cunningham, “Treading Water: Americans' Access to Needed Medical Care, 1997-2001,” Center for Studying Health System Change, Tracking Report, Vol. 1, March 2002.

- Allison Liebhaber and Joy M. Grossman, “Physicians Slow to Adopt Patient E-mail,” Center for Studying Health System Change, Data Bulletin No. 32, September 21, 2006.

- “Patients Want Online Communication With Their Doctors,” Medscape Medical News , April 17, 2002; and “Patient/Physician Online Communication: Many Patients Want It, Would Pay for It, and It Would Influence Their Choice of Doctors and Health Plans,” Harris Interactive Healthcare News , Vol. 2, No. 8, April 10, 2002.

- Sandra G. Boodman, “Calling Doctor Dappen,” Washington Post , September 9, 2003. Also see Mike Norbut, “Doctor Redefines Visits with Phone, E-mail,” American Medical News , October 20, 2003; and Christine Wiebe, “Doctors Still Slow to Adopt E-mail Communication,” Medscape Money & Medicine, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2001.

- Wiebe, “Doctors Still Slow to Adopt Email Communication.” Among health plans that do pay, some will not compensate doctors for e-mail exchanges unless the patient has first been examined in an office. Other insurers reimburse less for e-mail exchanges than for in-person visits. See Milt Freudenheim, “Digital Rx: Take Two Aspirins and E-Mail Me in the Morning,” New York Times , March 2, 2005. An exception is Blue Shield of California, which pays physicians the same for an e-mail consultation ($25) as it does for an office visit. David Koenig (Associated Press), “A Few Doctors Seeing Patients Online,” Akron Beacon Journal , December 21, 2003. The American Medical Association has created a reimbursement code for online consultation patients, making it easier for physicians to get paid.

- Chris Talbott (Associated Press), “Shortage of Doctors Affects Rural U.S.,” Boston Globe , July 21, 2007.

- Dennis Cauchon, “Medical Miscalculation Creates Doctor Shortage,” USA Today , March 25, 1005.

- Janet Coffman, Brian Quinn, Timothy T. Brown and Richard Scheffler, “Is There a Doctor in the House? An Examination of the Physician Workforce in California over the Past 25 Years,” Nicholas C. Petris Center on Health Care Markets and Consumer Welfare, School of Public Health, University of California-Berkley, June 2004. Available: http://www.petris.org/Docs/CADocs.pdf. Accessed October 23, 2007.

- “Addressing the Problem of Low Acuity Non-Emergent ER Visits,” Mercer Human Resources Consulting, January 2006.

- “Overuse of Emergency Department among Insured Californians.”

- Mercer pegs the average cost per emergency room visit at $383, or about two to three times as costly as a traditional physician office visit. “Addressing the Problem of Low Acuity Non-Emergent ER Visits,” Mercer Human Resources Consulting, January 2006.

- See Occupational Health Management, “Self-Care Can Save Millions in Health Costs: Unnecessary Visits to ED, other Costs Avoided,” Occupational Health Management , November 2001.

- Sally Trude, “So Much to Do, So Little Time: Physician Capacity Constraints, 1997-2001,” Center for Studying Health System Change, Tracking Report No. 8, May 2003.

- For examination of the literature on doctor-patient communication, see Ronald M. Epstein, Brian S. Alper and Timothy E. Quill, “Communicating Evidence for Participatory Decision-Making,” Journal of the American Medical Association , Vol. 291, No. 19, May 19, 2004.

- K. Binns and Q. Homan, “Consumers Demand Personalized Services to Manage Their Health,” ADVANCE for Health Information Executives , Vol. 5, 2001, page 88.

- See Epstein, Alper and Quill, “Communicating Evidence for Participatory Decision-Making.”

- Robert J. Blendon et al., “Views of Practicing Physicians and the Public on Medical Errors,” New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 347, No. 24, December 12, 2002, pages 1,933-40.

- “Quality Matters: Care Coordination,” Commonwealth Fund, Vol. 24, May/June 2007.

- Ross DeVol and Armen Bedroussian, “ An Unhealthy America: The Economic Burden of Chronic Disease — Charting a New Course to Save Lives and Increase Productivity and Economic Growth,” Milken Institute, October 2007.

- “Disease Management: The New Tool for Cost Containment and Quality Care,” Health Policy Studies Division, National Governors Association, Issue Brief, February 2003.

- Thomas Bodenheimer, “Disease Management — Promises and Pitfalls,” New England Journal of Medicine , Vol. 340, No. 15, April 15, 1999, pages 1,202-05.

- Ibid.

- “Disease Management: The New Tool for Cost Containment and Quality Care.”

- For instance, see Gina Kolata, “Looking Past Blood Sugar to Survive with Diabetes,” New York Times , August 20, 2007.

- Information obtained from Solantic.com Web site. See also Milt Freudenheim, “Attention Shoppers: Low Prices on Shots in Clinic,” New York Times , May 14, 2006.

- Ibid.

- Maureen Glabman, “What Doctors Don't Know About the New Plan Designs,” Managed Care Magazine , January 2006.

- See Jason Robertson, “Doctor Taking Care of Small Business,” Dallas Morning News , April 30, 2007.

- Laurance Baker, Jeffery Rideout, Paul Gertler and Kristina Raube, “Effect of an Internet-Based System for Doctor-Patient Communication on Health Care Spending,” Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association , Vol. 12, No. 5, May 19, 2005, pages 530-36.

- Office visits were 7 percent to 10 percent lower than for a control group. See Yi Yvonne Zhou et al., “Patient Access to an Electronic Health Record with Secure Messaging: Impact on Primary Care Utilization,” American Journal of Managed Care , Vol. 13, No. 7, July 2007. A study from Norway also found patients able to e-mail their doctor had fewer office visits. See Trine Strand Bergmo et al., “Electronic Patient-Provider Communication: Will It Offset Office Visits and Telephone Consultations in Primary Care?” International Journal Medical Informatics , Vol. 74, No. 9, 2005, September 2005, pages 705-10.

- April W. Armstrong et al., “Economic Evaluation of Interactive Teledermatology Compared with Conventional Care,” Telemedicine and e-Health , Vol. 13, No. 2, April 2007, pages 91-99.

- Abrar A. Qureshi et al., “Willingness to Pay Stated Preferences for Telemedicine Versus In-Person Visits in Patients with a History of Psoriasis or Melanoma,” Telemedicine and e-Health , Vol. 12, No. 6, December 2006, pages 639-40.

- “PPO to Pay Physicians for Web Consultations – First Health Group – Company Operations,” Health Management Technology , July 2000.

- Warner V. Slack, “A 67-Year-Old Man Who E-Mails His Physician,” Journal of the American Medical Association , Vol. 292, No. 18, November 10, 2004, pages 2,255-61.

- Zhou et al., “Patient Access to an Electronic Health Record with Secure Messaging: Impact on Primary Care Utilization.”

- For an example of a similar service where physicians make costly house calls to a hotel room, see Jennifer Alsever, “Retro Medicine: Doctors Making House Calls (for a Price),” New York Times , September 23, 2007.

- “Addressing the Problem of Low Acuity Non-Emergent ER Visits,” Mercer Human Resources Consulting, January 2006.

- Information obtained from conversations with TelaDoc executives in addition to the TelaDoc Web site.

- TelaDoc customer surveys from January 1, 2007, through May 30, 2007. If a call is not returned in under three hours the consultation is free — something that happens less than 3 percent of the time.

- Ibid.

- Ibid. Sixty-nine percent rate the TelaDoc service as excellent. Nearly 22 percent rate it as good.

- See Epstein, Alper and Quill, “Communicating Evidence for Participatory Decision-Making.”

- TelaDoc customer surveys from January 1, 2007, through May 30, 2007.

- For a brief literature review of the history of telemedicine, see Nancy Brown, “A Brief History of Telemedicine,” Telemedicine Information Exchange, May 30, 1995. Available at http://tie.telemed.org/articles/article.asp?path=articles&article=tmhistory_nb_tie95.xml. Accessed September 19, 2007.

- At the time, there was no way to estimate the cost of the telemedicine network and therefore no way to calculate net gains. However, this technology is now readily available and relatively inexpensive. See D. S. Watson, “Telemedicine,” Medical Journal of Australia , Vol. 151, No. 2, 1989, pages 62-71.

- Conversations with Arthur Stern, corporate marketing specialist at Doctor On Call and the Doctor On Call Web site.

- See McKesson Web site at http://www.mckesson.com/en_us/McKesson.com/For+Healthcare+Providers/Hospitals/Contact+Center+Management/ASK-A-NURSE.html.

- See Fonemed Web site at http://www.fonemed.com.

- See Carenet Web site at http://www.Carenet.com.

- Cristiano Antonelli, Aldo Geuna and W. Edward Steinmueller, “Information and Communication Technologies and the Production, Distribution and Use of Knowledge,” International Journal of Technology Management, Vol. 20, No. 1/2, 2000, pages 72-94.

- In 1999, Bob Pringle, president of health content provider Inteli-health, estimated there were 15,000 to 20,000 Web sites dedicated to health-related content. See Robert McGarvey, “Online Health's Plague of Riches,” Tech Insider , September 29, 1999. The Internet Healthcare Coalition claims more than 20,000 Web sites dedicated to health care. See “Tips for Healthy Surfing Online,” Internet Healthcare Coalition, 2002. This is consistent with estimates from the Journal of Medical Internet Research . See Roberto J. Rodrigues, “Ethical and Legal Issues in Interactive Health Communications: A Call for International Cooperation,” Journal of Medical Internet Research , Vol. 2, No. 1, 2001.

- Susannah Fox, “Online Health Search 2006,” Pew Charitable Trusts, Pew Internet and American Life Project, October 29, 2006.

- Devon M. Herrick and John C. Goodman, “ The Market for Medical Care: Why You Don't Know the Price; Why You Don't Know about Quality; And What Can Be Done about It,” National Center for Policy Analysis, Policy Report No. 296, March 2007. Available at http://www.ncpathinktank.org/pub/st/st296/.

- J. Finkelstein and Robert Friedman, “Telecommunication Offers Solution to Chronic Pulmonary Disease Management,” Advance Managers Respiratory Care , Vol. 9, No. 5, 2000, pages 12-14.

- Richard Hillestad et al., “Can Electronic Medical Record Systems Transform Health Care? Potential Health Benefits, Savings, and Costs,” Health Affairs , Vol. 24, No. 5, September/October 2005, pages 1,103-17.

- For instance, a doctor and nurse practitioner working as a team were better able to manage chronic conditions than a physician working alone. See David Litaker, “Physician-nurse practitioner teams in chronic disease management: the impact on costs, clinical effectiveness, and patients' perception of care,” Journal of Interprofessional Care , Vol. 17, No. 3 August 2003, pages 223–37.

- Jane Anderson (editor), “Use of Telemedicine Tools Grows within DM,” Disease Management News , Vol. 12, No. 8, 2007.

- For instance, children assigned to interactive disease management for asthma fared better than those in a control group with traditional disease management. See Ren-Long Jan et al., “An Internet-Based Interactive Telemonitoring System for Improving Childhood Asthma Outcomes in Taiwan,” Telemedicine and e-Health , Vol. 13, No. 3, June 2007, pages 257-68.

- Paula de Toledo et al., “Telemedicine Experience for Chronic Care in COPD,” IEEE Transactions on Information Technology in Biomedicine , Vol. 10, No. 3, July 28, 2006, pages 567-73.

- Craig Lehmann and Jean Marie Giacini, “Pilot Study: The Impact of Technology on Home Bound Congestive Heart Failure Patients,” Home Health Care Technology Report , Vol. 1, No. 4, May/June 2004, pages 50, 59-60.

- Ren-Long Jan et al., “An Internet-Based Interactive Telemonitoring System for Improving Childhood Asthma Outcomes in Taiwan.”

- Diabetics in the treatment group had blood glucose readings (HbA1c) of 6.38 percent compared to the control group readings of 6.99 percent. See Hyuk-Sang Kwon et al., “Establishment of Blood Glucose Monitoring System Using the Internet,” Diabetes Care , Vol. 27, No. 2, 2004, pages 478-83.

- Robert M. Wachter, “International Teleradiology,” New England Journal of Medicine , Vol. 354, No. 7, February 16, 2006, pages 662–63; and Arnold Milstein and Mark Smith, “Will the Surgical World Become Flat?” Health Affairs , Vol. 26, No. 1, January/February 2007.

- Robert M. Wachter, “The ‘Dis-location' of U.S. Medicine — The Implications of Medical Outsourcing,” New England Journal of Medicine , Vol. 354, No. 7, February 16, 2006. For a layman's view of outsourcing radiology, see Associated Press, “Some U.S. Hospitals Outsourcing Work,” MSNBC.com, December 6, 2004. Available at www.msnbc.msn.com/id/6621014/. Accessed April 27, 2007.

- Associated Press, “Some U.S. Hospitals Outsourcing Work,” MSNBC.com, December 6, 2004. Available at www.msnbc.msn.com/id/6621014/. Accessed April 27, 2007. See Nighthawk Radiology Services Web site: www.nighthawkrad.net/.

- Rob Stein, “Hospital Services Performed Overseas,” Washington Post , April 24, 2005.

- Nearly 160 million Americans are covered through employer-sponsored health plans. See David Blumenthal, “Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance in the United States — Origins and Implications,” New England Journal of Medicine , Vol. 355, No. 1, July 6, 2006, pages 82-88.

- For a discussion, see John C. Goodman and Gerald L. Musgrave, Patient Power: Solving America's Health Care Crisis (Washington, D.C.: Cato Institute, 1992).

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, “National Health Expenditures by Type of Service and Source of Funds: Calendar Years 2005-1960,” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2006. Available at http://www.cms.hhs.gov/NationalHealthExpendData/downloads/nhe2005.zip. Accessed January 2006. Also see Katharine Levit et al., “Trends in U.S. Health Care Spending, 2001,” Health Affairs , Vol. 22, No. 1, February 2003, pages 154-64.

- However, Alissa R. Spielberg argues that within a few years after the telephone was invented, physicians felt obligated to accept calls from patients by phone — although physicians had worries about getting paid for phone consultations. See Alissa R. Spielberg, “On Call and Online: Sociohistoric, Legal, and Ethical Implications of E-mail for the Patient-Physician Relationship,” Journal of the American Medical Association , Vol. 280, No. 15, October 21, 2998, pages 1,353-59.

- Many physicians felt practicing telemedicine promoted substandard care and hurt the integrity of the medical profession. See Claude S. Fischer, America Calling: The Social History of the Telephone to 1940 (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1992), page 176; and Stanley Joel Reiser, Medicine and the Reign of Technology (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1978), page 199.

- See John W. Jones, “Legal Obstacles to Internet Prescribing,” Physician's News Digest , June 2004.

- Mary Schmeida, Ramona McNeal and Karen Mossberger, “Policy Determinants Affect Telehealth Implementation,” Telemedicine and e-Health , Vol. 13, No. 2, April 2007, pages 100-107.

- Reuben A. Kessel, “Price Discrimination in Medicine,” Journal of Law and Economics , Vol. 1, October 1958, pages 43-44. The theory is that price-cutting would lead to a situation where fees would be too low for a physician to render quality services. For a review of health insurance regulation, see John C. Goodman, The Regulation of Medical Care: Is the Price Too High? (San Francisco, Calif.: Cato Institute, 1980). Also see Greg Scandlen, “100 Years of Market Distortions,” Consumers for Health Care Choices, May 22, 2007.

- The states have long licensed and regulated physicians with the ostensible goal of maintaining the quality of medical care. See Paul B. Ginsburg and Ernest Moy, “Physician Licensure and the Quality of Care: The Role of New Information Technologies,” Regulation , Cato Institute, Vol. 15, No. 4, Fall 1992. For a literature review of the history of medical licensure, see Goodman and Musgrave, Patient Power: Solving America's Health Care Crisis.

- Reuben A. Kessel, “Price Discrimination in Medicine,” Journal of Law and Economics , Vol. 1, October 1958, pages 43-44. For a review of health insurance regulation, see Goodman, The Regulation of Medical Care: Is the Price Too High?

- Ginsburg and Moy, “Physician Licensure and the Quality of Care: The Role of New Information Technologies.”

- Mark A. Cwiek et al., “Telemedicine Licensure in the United States: The Need for a Cooperative Regional Approach,” Telemedicine and e-Health , Vol. 13, No. 2, April 2007, pages 141-47.

- Specifically, some state medical boards consider it unethical for physicians to prescribe treatments online (and therefore prohibit them from doing so through regulation), unless there is a bona fide doctor/patient relationship that begins with a face-to-face meeting and physical examination. See John W. Jones, “Legal Obstacles to Internet Prescribing,” Physician's News Digest , June 2004.

- For a discussion, see Devon M. Herrick, “Demand Growing for Corporate Practice of Medicine,” Health Care News , Heartland Institute, January 1, 2006.

- Nicole Huberfeld, “Be Not Afraid of Change: Time to Eliminate the Corporate Practice of Medicine Doctrine,” Health Matrix , Vol. 14, No. 2, 2004, pages 243-91.

- For example, Harvard Business School professor Regina Herzlinger, a strong proponent of consumer-driven health care, has proposed a regulatory body modeled on the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission to oversee transparency in health care. See Regina E. Herzlinger, “Testimony Before the Subcommittee on Health of the House Committee on Ways and Means,” July 18, 2006. Available at http://waysandmeans.house.gov/hearings.asp?formmode=view&id=5139. Accessed July 21, 2006.

- John C. Goodman, President, National Center for Policy Analysis, “Health Savings Accounts,” Testimony Before the U.S. Senate Special Committee on Aging, May 19, 2004.

- Ibid.

- John Irwin and Edwin Parker, “Benefits of Telemedicine,” Telemedicine Association of Oregon, January 16, 2004. Available at: http://www.ortcc.org/PDF/BenefitsofTelemedicine.pdf. Accessed September 26, 2007.

- Cwiek et al., “Telemedicine Licensure in the United States: The Need for a Cooperative Regional Approach.”

- John C. Goodman, “Making HSAs Better,” National Center for Policy Analysis, Brief Analysis No. 518, June 30, 2005.

- Huberfeld, “Be Not Afraid of Change: Time to Eliminate the Corporate Practice of Medicine Doctrine.”

- Kate Murphy, “What Pilots Can Teach Hospitals about Patient Safety,” New York Times , October 31, 2006.

- Research at NASA found most aviation accidents were caused by human error and often could have been prevented by better communication among the flight crew. A protocol called “crew resource management” is now standard training for all flight crews. See “New Surgeon-In-Chief Adapts Airline Safety Program to Improve Patient Safety,” Medical News Today , November 13, 2006. Available at http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/medicalnews.php?newsid=56496. Accessed December 14, 2006. Also see Eric J. Thomas and Robert L. Helmreich, “Will Airline Safety Models Work in Medicine?” in Marilynn M. Rosenthal and Kathleen M. Sutcliffe, eds., Medical Error: What Do We Know? What Do We Do? (San Francisco, Calif.: Jossey-Bass, 2002), pages 217-34.

Devon Herrick , Ph.D., is a senior fellow with the National Center for Policy Analysis. He concentrates on such health care issues as Internet-based medicine, health insurance and the uninsured, and pharmaceutical drug issues. His research interests also include managed care, patient empowerment, medical privacy and technology-related issues. Herrick also serves as the Chair of the Health Economics Roundtable of the National Association for Business Economics.

Herrick received a Ph.D. in Political Economy and a Master of Public Affairs degree from the University of Texas at Dallas with a concentration in economic development. He also holds an M.B.A. with a concentration in finance from Oklahoma City University and an M.B.A. from Amber University, as well as a B.S. in accounting from the University of Central Oklahoma.