Medicare reform will soon be front and center in the public policy arena. The reason: Projections in the past two years for Medicare's deteriorating finances have triggered a legal requirement for the President to propose reform legislation within 15 days of the release of the next federal budget. Congress must consider the president's proposal on an expedited basis.

This paper proposes a comprehensive reform that addresses both Medicare's funding and its spending. It has these features:

- The cost of the reform is spread across generations instead of being shifted to future taxpayers.

- The reform gives retirees control over more of the health care dollars they spend and this patient control grows through time.

- The reform creates incentives for retirees at all income levels to consider the cost of the health care they consume, allowing beneficiaries to reap more of the financial benefits from their prudent decisions and requiring them to bear more of the cost if they choose to spend more.

- The reforms will allow patients to choose between health care and other goods and services on a level playing field — without distortions created by the tax code.

- Because an increasing portion of spending will be controlled by patients using their own health care dollars, health care providers will have new incentives to compete on price and quality.

The most novel feature of this proposal is the creation of Health Insurance Retirement Accounts (HIRAs). Through these accounts current workers will partially prepay future Medicare costs and thereby reduce the projected tax burden on future workers. Under this reform:

- Workers will contribute a fixed percentage of their total wage income to a HIRA during their working lives.

- When they enroll in Medicare at age 65, beneficiaries will use their HIRA balances to purchase an annuity paying an annual fixed sum to a spending account, such as a Roth Health Savings Account (HSA).

- Beneficiaries will use their HIRA annuities to pay for a share of their Medicare costs and any funds remaining at the end of the year can be withdrawn tax free (like a Roth IRA) and spent on nonmedical goods and services.

- Retirees who have higher incomes during their working years will have higher annuities and therefore will face greater cost sharing during their retirement years.

- The annuities will replace government spending obligations, and as the annuities grow through time they will relieve an increasing amount of the burden on future taxpayers that would exist under the current financing arrangement.

- The new economic incentives for patients to become more prudent consumers of health care will further reduce the funding burden on the next generation by reducing both the level and rate of growth in health care spending by retirees.

Under reasonable assumptions:

- Average income workers entering the labor market today will have annuities that pay an amount equal to 29 percent to 59 percent of their projected spending on Medicare covered services at the midpoint of their retirement years.

- High income workers will have annuities that pay 46 percent to 95 percent of their retirement health care costs.

- By midcentury, reformed Medicare spending is estimated to be 20 percent to 35 percent less than the current program.

- By midcentury or earlier, total spending on the reformed program, including contributions to HIRAs, is estimated to be less than the spending on the current program.

This reform proposal should appeal to reformers across the political spectrum because it reduces the tax burden on future workers, puts Medicare on a sounder footing, retains the progressivity of the current program's funding, and produces cost sharing incentives that rise with lifetime income.

[page]Is there such a thing as a Medicare reform proposal everyone can love? Probably not, but individuals from across the ideological spectrum must admit that, under reasonable assumptions, the share of the nation's income devoted to retirees' health care will increase dramatically over the next two decades. Since Medicare pays most of retirees' health care bills, taxpayers will end up paying for much of the projected increase in spending. In order to avert substantial tax increases, Medicare reform must be addressed in advance of the baby boomers' retirement.

“Medicare reform must address both spending and funding.”

The Funding Warning. This year, reforming Medicare will be high on the policy agenda because of a “warning” about the projected deterioration of the program's finances in the 2007 Medicare Trustees report. By law, the President must submit a Medicare reform proposal to Congress within 15 days of submitting the 2009 budget, and Congress must consider it in an expedited manner. 1 This means that Medicare reform must be addressed by Congress in February 2008.

What has triggered this series of events is a finding by the Medicare Trustees. Medicare's funding from general revenues, the difference between its total spending and its tax and premium revenues, is projected for each of the next 75 years in each year's Trustees Report. If the general revenue requirement is projected to exceed 45 percent of total spending within the first seven years of the projection period for two consecutive Trustees Reports, a funding warning is required. The 45 percent threshold was breached in both the 2006 and 2007 reports.

Congressional Response to the Funding Warning. Congress will be hard-pressed to ignore the warning, even though some are already downplaying its significance and importance. During both the Clinton and Bush Administrations, the Trustees have counseled that timely action is preferable to delayed reaction. Whether this will result in timely reform is an open question. However, everyone agrees that some sort of reform is inevitable in the long run.

A Comprehensive Reform Proposal. This study outlines a reform proposal that has components policymakers from across the political spectrum will find attractive. While it won't please everyone, it covers the gamut of concerns of most would-be reformers:

- First, it addresses the important issues of generational equity by requiring each cohort of workers to prefund some of their future retirement health care costs.

- Second, it gives retirees more control over the money they spend on health care.

- Third, it creates incentives for retirees across all income levels to consider the cost of the health care they consume.

- Fourth, it creates incentives for health care providers to offer their patients more efficient and higher-quality medical care.

Through the years, most Medicare reform proposals have focused on controlling spending, while leaving the funding mechanisms essentially untouched. This comprehensive proposal addresses both Medicare spending and funding.

[page]“To fund projected Hospital Insurance (Part A) spending would require tripling the Medicare payroll tax to 8.7 percent.”

In addition to the Medicare funding warning, there are other indicators of the need for reform. This year and every year hereafter, expenditures for Medicare Hospital Insurance (Part A) are expected to exceed the revenues dedicated to it: the Medicare portion of the payroll tax (2.9 percent) and Medicare's share of income taxes paid on Social Security benefits. 2

Unfunded Obligations. The annual Medicare Trustees Report provides measures of the generational equity problem in Medicare. Each year the actuaries calculate the program's unfunded obligation, defined as the present value of the difference between projected program costs and revenues.

- For Medicare Part A, the unfunded obligation over the next 75 years is $11.6 trillion. Looking indefinitely into the future, the unfunded liability is $29.5 trillion.

- To make Medicare Part A solvent in the long run would require an immediate tax increase of 5.8 percentage points, bringing the total Medicare payroll tax rate up to 8.7 percent. 3

- Further, these funds would have to be invested in assets earning at least the rate of return on government bonds.

“To fund all projected Medicare spending would require a 17.5 percent payroll tax.”

Additional Revenue Requirements. In addition to the projected Medicare Part A funding deficits that must be paid by future generations, Supplementary Medicare Insurance (Medicare Part B), primarily covering physicians' and outpatient services, and coverage for pharmaceuticals (Medicare Part D) will require a growing share of projected federal revenue. After accounting for the premiums paid by beneficiaries, Medicare Parts B and D currently require more than $1 of every $10 of federal tax revenues other than those taxes (mainly payroll taxes) that support social insurance programs. In the future, things will get worse. When all three parts are combined, the Trustees' project that Medicare deficits will require more than $1 out of every $5 federal revenues that aren't already dedicated to social insurance by 2020. 4

Spending on Elderly Entitlements. Over the next several decades, spending on Medicare and Social Security as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) will rise for two reasons: (1) the number of beneficiaries will grow relative to the number of taxpayers and (2) health care spending per capita will grow more rapidly than GDP per capita. If taxes rise to meet this increased spending, total federal expenditures will rise from 20 percent of GDP today to 25 percent by the time the last of the Baby Boom generation enters retirement. As a result, tax revenues as a share of the nation's economy will have to rise by one-fourth over the next 25 years. By midcentury, taxpayers will spend an amount equal to almost one-third (31 percent) of their wages just to support Medicare and Social Security. That is more than double the current payroll tax burden.

The reform proposal is designed to reduce Medicare's future projected costs by changing retirees' incentives as well as the generational burden of the program. Following is a description of the elements of the plan, the assumptions behind them and how they work together. Finally, the effects of the plan on Medicare's finances and health care spending by seniors are projected, using projections from the 2007 Medicare Trustees Report as a baseline.

[page]The centerpiece of the reform is the creation of Health Insurance Retirement Accounts (HIRAs) in which individuals put aside funds during their working years to partially prepay their retirement health care expenses.

“Health Insurance Retirement Accounts (HIRAs) would allow workers to save for their retirement health care expenses.”

Deposits to HIRAs. All workers will have the same fixed percentage deducted from their paycheck, just as they now do with the current Medicare (HI) payroll taxes. These deductions, however, will be deposited in an individual's HIRA, rather than going to the general revenue coffers of the federal government. Further, since these deposits (just like current Medicare payroll taxes) will be subject to income taxation, HIRA are funded with after-tax dollars. This means that the use of the funds during in retirement will be tax free, similar to withdrawals from a Roth IRA (Individual Retirement Account). 5

Contributions to the individual HIRAs will be deposited with private sector insurance/annuity providers who will be responsible for investing the funds. Although HIRAs are nominally the property of the individual account-holders, they will not have access to these funds unless they reach age 65. Just as with current Medicare, the receipt of any benefits from a HIRA is contingent on surviving to the age of eligibility. HIRAs, therefore, should be thought of as insurance that is payable only if the worker lives long enough. HIRAs are not part of a person's estate any more than current Medicare is part of anyone's estate. 6

Restructured Medicare Insurance. At the outset of the reform, Medicare Parts A, B and D will be combined into a single insurance plan, similar to current Medicare Part C (Medicare Advantage). Every individual will face a base deductible, or defined cost-sharing requirement, that will be indexed to grow at the same rate as overall per capita Medicare spending. The base deductible, and the cost sharing it requires, would apply immediately upon adoption of the reform to all current beneficiaries, even though they have no HIRA balance. The initial base deductible used in the projections for this study is $2,500, which is in the neighborhood of a senior's current combined average spending for an individually purchased medigap policy and on out-of-pocket Medicare expenses. Current beneficiaries would continue to pay their share of Medicare expenses through premium payments, but their cost sharing would be limited to the indexed base amount.7 7

“Workers would contribute 4 percent of their total earnings to their individual HIRAs.”

For future beneficiaries, each individual's total Medicare cost sharing will equal the base deductible plus the amount of the annuity from that individual's HIRA. All retirees born in the same year, regardless of income, will face the same indexed base deductible. The additional cost sharing requirement will depend on the annuity made possible by the individual's HIRA, which is in turn based on the beneficiary's preretirement income. Thus, while the base deductible is not income related total deductibles rise with income since the level of HIRA annuity funding rises with income.

The exceptions are low-income participants. Each year the federal government will make additional contributions to their Health Savings Account ( HSA) or similar health spending account to cover part of the deductible. In many cases, the low income retirees' remaining cost sharing, after the government contribution, will be covered by HSA funds they roll over from year to year. Retirees who receive government contributions could be required to roll over any remaining contribution until the base deductible is covered. Once this requirement is satisfied they would be free to spend any remaining funds in their accounts. [See the sidebar on “Benefits and Incentives for Low-Income Workers.”]

HIRA Contribution Rate. It is assumed that all workers age 64 and younger in 2007 make contributions of 4 percent of their total earnings to these HIRA accounts in addition to the taxes necessary to pay benefits to current retirees. Thus, HIRA contributions will reduce workers' take-home pay. 8

While additional contributions of 4 percent may seem burdensome on current workers, they must be considered in light of the alternative means of financing Medicare in the long run. The authors previously estimated that an immediate payroll-tax increase to 17.5 percent would be necessary to fund all parts of the current Medicare program indefinitely using Trust Fund accounting. 9 Considering the growing burden of Medicare Parts B and D on federal revenue in addition to the tax rate increases that would be necessary just for Medicare Part A solvency, the 4 percent HIRA contribution rate is not unreasonable.

Rate of Return on HIRAs. The accumulation phase is the build-up of the funds in HIRAs before workers retire. The decumulation phase is the period after retirement, when beneficiaries begin using their HIRA annuities for health care spending. The initial estimates assume that HIRA balances will earn a 2.9 percent real rate of return (which is roughly the return paid on federal government bonds) during both the accumulation and decumulation phases. 10 Because there is much debate over the appropriate rate to use in evaluating Social Security and Medicare reforms that involve investments in private bonds and equities, a second set of projections uses a 5.2 percent rate of return during the accumulation phase — which is closer to returns in the private capital market.

Benefits and Incentives for Low-Income Workers

How will very low-income individuals afford even the base deductible? Before considering the solution to that problem, consider three questions that any reform must deal with if it is to succeed in dealing with Medicare's funding problems:

- Does the plan give Medicare patients the incentive to choose between health care and other uses of money?

- Does the plan give providers of care the incentive to compete based on price and/or quality of care?

- Does the plan allow Medicare patients to have the same access to doctors, hospitals, clinics and so forth that non-Medicare patients have?

If the base deductible were waived for low-income Medicare recipients, the answer to the first question would definitely be “no.” If low-income patients face no out-of-pocket costs, the answer to the second question would also be “no,” since providers would not compete for them on the basis of price. Further, if doctors' time is rationed by waiting rather than by price, the answer is most probably “no” to the third question as well. An effective reform must encourage all users to participate in the same system. The more that low-income individuals view their spending as using their own money, the more likely they are to have the same access to providers as other patients.

To make Medicare participants care about cost using significant deductibles while ensuring that health care is affordable and accessible to those with low incomes, the government would make deposits to the HSAs of low-income participants (adding to their annual annuity payment) to cover a large part of their deductibles. Specifically, their out-of-pocket cost sharing would be limited so that they never face higher out-of-pocket costs as a percentage of their Social Security benefits than do retirees who had medium earnings. In this way low-income participants would have the income to buy needed health care. Yet, they will treat these funds as any other source of income since the money, if not spent on health care, is theirs to spend on other goods and services.

Annuities and Spending Funded from HIRAs. Once people reach the eligibility age, their HIRA balances will be used to purchase annuities that will deposit a fixed sum into their HSAs every year for the rest of their lives. For example, the day after their 65th birthday they will receive their first full-year payment. The payment will be deposited in their HSA and can be spent on health care during the coming year. Individuals are free to spend any annuity amounts remaining at the end of each year on other consumption, without penalty, or they can roll the balances over for use in the following years (to cover the base deductibles, for example). As a result, the annuity payment is equivalent to other after-tax income. If a senior dies during the year, any balance remaining in the HSA is part of their estate.

“HIRAs will fund annuities retirees can spend on health care each year, and they can use unspent funds for other consumption.”

Incentives under the Reformed System. The proposed reform is based on high-deductible insurance and greater retiree command over health care dollars. It produces better incentives for both demanders (patients) and suppliers (providers) of health care. Further, this design makes reformed Medicare more like true insurance, in stark contrast to the first-dollar coverage that is prevalent in the health care market today. Because patient cost sharing expenses will be met with after-tax dollars, health care will compete with other consumption choices on a level playing field. As a result, patients themselves will be choosing between health care and other uses of money instead of the bureaucratic rationing of health care that sometimes occurs in other countries.

All the evidence suggests that individuals who have higher deductibles spend less on health care, often with no detriment to health outcomes. Higher deductibles may also reduce the growth rate of health care spending. Note that the higher deductibles generated by higher earnings (and therefore higher HIRA deposits) do not impose a financial burden in retirement on the individual because they are covered dollar-for-dollar by higher annuity payments.

The estimates of the effect of higher deductibles on health care spending are based on the results of the RAND Health Insurance Experiment of the late 1970s. The experiment tracked the behavior of patients facing different health insurance cost-sharing arrangements. Even though the experiment did not include elderly individuals, its findings provide the best evidence of the effects of cost-sharing on health care spending and utilization of services. The RAND results are used to identify the upper and lower bounds of a range of effects on health care spending that may result from the proposed reforms. 11 [See the sidebar below on “Effects of Deductibles on Health Care Spending.”]

Other Insurance Options. The high-deductible insurance plan is a point of reference. It helps identify the government's obligation (expected expenses above the deductible) in each and every year. However, once the government (taxpayer) obligation has been determined, other insurance arrangements are possible. Specifically, Medicare could pay a risk-adjusted premium on behalf of the beneficiary to an HMO, to a plan with flexible deductibles (high for some services and low for others) or to some other plan. Medicare's payment to a potential insurer would be identified as the expected spending above the retiree's total deductible given his or her health status. The senior could add to the government's premium payment with a payment from his HSA, if needed. This flexibility would allow the marketplace to discover new and better ways of meeting seniors' insurance and health care needs.

“Higher income workers with larger annuities will face higher total deductibles.”

Distributional Effects of the Reform. The reform plan treats beneficiaries with different lifetime earnings differently in terms of the insurance package they receive. By contrast, the current Medicare system treats low- and high-income retirees the same in many respects. 12 Both groups face the same deductibles and copays for Medicare Parts A, B and D. They also have identical Medicare premiums of $93.50 per month for Part B deducted directly from their Social Security checks (as long as their annual incomes are less than $80,000 for individuals or $160,00 for a couple). 13 If they choose the same Part D policy, the premiums are identical across income classes and are also deducted directly from their Social Security checks. However, to fund Part A, Medicare collects payroll taxes that are proportional to income and uses other taxes (primarily income taxes paid by higher income workers) to fund some spending on Parts B and D.

The accumulated value of high-income workers' payroll taxes in support of Medicare Part A combined with their income taxes in support of Medicare Parts B and D are substantially greater than the similar accumulated value of low-income workers' tax payments. Over a lifetime, high income retirees will pay more taxes than lower income retirees, but they will receive an insurance benefit package with identical coverage.

By contrast, under the HIRA reform higher income workers will receive higher annuity payments from their HIRA account accumulations and face higher total deductibles. As a consequence, they will pay for more of their health care during retirement than lower income workers. Retirees who have low lifetime earnings will have lower annuities and consequently lower total deductibles.

Viewed over a lifetime, the HIRA reform is similar to the present program in terms of within-generation redistribution through the program's funding. However, the HIRA reform makes the current within-generation financing arrangement explicit. And the differential impact of the total deductibles that rise with income will produce quite different incentive effects than the uniform deductibles and copays under the current structure.

“Each generation of workers will save to pay some of their retirement health care costs.”

Effects on Generational Equity. Medicare's current pay-as-you-go financing arrangement effectively transfers the costs of the program to the next generation of taxpayers. Further, given the surge in retirees relative to workers that will occur as a result of the retirement of the baby boomers and the projected increase in health care consumption by the retired population, future taxpayers will have to bear the cost of a growing program.

The reform proposal addresses Medicare's generational inequity by having members of each generation of workers pay more of the cost of their own health care through partial prepayment. This reduces the burden on the next generation by having current workers fund more of the burden of their own benefits through their HIRAs. It also reduces the burden on the next generation by changing the health care consumption incentives of retirees, as upfront deductibles make retirees at every income level more cost conscious.

Why should the current generation take on this challenge? Simply put, a structural reform at this time may be in its best interest. Absent reform, budgetary pressures may force politicians to reduce projected benefits for future retirees. But those future retirees are the workers of today. Partial prepayment is also partial insurance against what many consider the inevitability of future benefit reductions.

[page]The following estimates show how the HIRA annuities combined with the base deductibles grow relative to projected spending for workers born in 1950, 1970 and 1990. 14

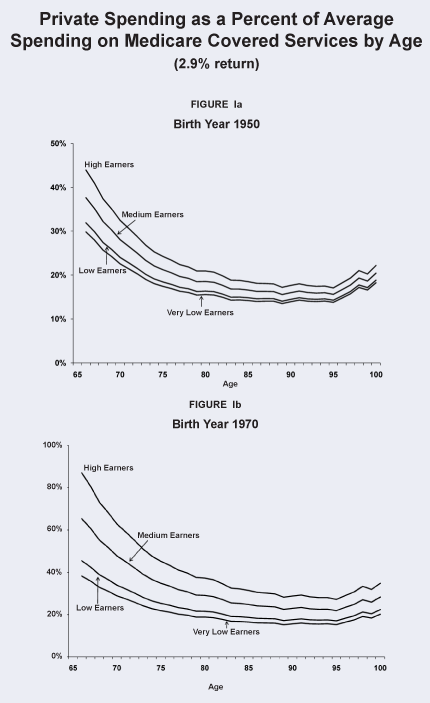

Figures Ia-Ic present total cost sharing as a percentage of projected total spending on Medicare-covered services for workers born in different years with different lifetime earnings. The figures show the size of the total cost sharing divided by estimated spending on Medicare-covered services at each age. 15

Workers Born in 1950. Figure Ia presents total cost sharing as a percentage of covered spending for workers born in 1950 for ages 66 to 100. 16 For purposes of this graph, average spending on Medicare-covered services by age is assumed to be equal across all income classes, even though there is evidence that expenditures increase with retiree income. Workers born in 1950 will be eligible for Medicare in 2015 and have eight years to accumulate funds in their HIRAs. Figure Ia shows that the total cost sharing for a high-income worker born in 1950 is greater than 40 percent of average spending for people ages 66 to 68. For the medium-income worker, total cost sharing exceeds 30 percent of average spending up to age 69. Thus, the total cost sharing for retirees who had medium or higher earnings will be more than 30 percent of average projected spending during the first years of retirement. 17

“The government will contribute to the accounts of low-income retirees.”

For members of the 1950 birth year, the real value of the base deductible (in 2007 dollars) is $2,974 when they retire. The real values of the HIRA annuities for low-, medium- and high-income retirees will be $528, $1,175, and $1,880, producing total cost sharing of $3,502, $4,148, and $4,854, respectively.

The government's contribution to the HIRAs of low-income retirees would be calculated as follows. The subsidy is set so that the low-income retiree's potential out-of-pocket spending is no larger than the medium retiree's spending as a share of their respective Social Security benefits. For example, the base deductible as a percentage of medium earner's Social Security benefit for workers born in 1950 is 17.6 percent. The low-income retiree would receive a $1,169 government contribution to their HIRA so that their maximum out-of-pocket cost of $1,805 is also 17.6 percent of their Social Security benefit. 18

“Average Medicare spending increases with age, so the percentage of spending that is privately funded falls.”

Workers Born in 1970. The ratios of cost sharing to total spending depicted in Figure Ib exhibit the same shape as those shown in Figure Ia, but the size of the ratios grows as the number of years of labor force participation increases. The members of the 1970 birth cohort are 37 in 2007 and have 28 years remaining in the labor force before retiring in 2035. The total cost sharing of the high-income members of this birth year is in excess of 60 percent of average projected spending on Medicare covered services to age 70. For medium earners, total cost sharing is above 60 percent of average covered spending up to the age of 67. In contrast to Figure Ia, where the HIRA annuity differences were small across income groups because of the short contribution period, the HIRA annuities here produce increasing dispersion in the total cost sharing across income groups. For example, at 75 years of age the total cost sharing requirement of high-income retirees is 31 percent higher than for low income retirees born in 1950, but for those born in 1970 the high-income retirees' total cost sharing is 79 percent higher.

Workers Born in 1990. Workers born in 1990 are 17 years old at the outset of the reform and have their entire work life to contribute to HIRAs. The high earners have total cost sharing in excess of average projected spending until they are 68 years of age. As shown in Figure Ic, medium earners start retirement with total cost sharing equal to 87 percent of average spending and deductibles in excess of 50 percent of average spending up to age 73.

“If the accounts of workers born in 1990 earn only the government's rate of return, higher wage workers would fund more than half of average spending on Medicare-covered services at age 75.”

As these figures indicate, the annuity payments combined with base deductibles indexed to the projected per capita Medicare spending will ultimately bring about significant cost sharing. At first, much of the total cost sharing is due to the indexed base deductible. For later birth cohorts the size of the HIRA annuity exceeds the base deductible.

Because the HIRA reform makes all future retirees more cost conscious than they would be under current Medicare, health care spending can be expected to decline relative to current projected spending. In addition, because total cost sharing rises with lifetime income, the level of cost consciousness will rise with income. Two methods of accounting for the effects of changing cost sharing are used to identify the cost paths depicted in Figures IIa and IIb. These (Methods 1 and 2) are based on the RAND health care experiment. [See the sidebar, “Effects of Deductibles on Health Care Spending.”] The estimates are derived by using the experience of the medium worker as the representative consumer.

Three series are presented in each graph. The Current Medicare series from the 2007 Medicare Trustees Report reflects total Medicare costs as a share of GDP. These costs must be paid through payroll taxes, taxes on Social Security benefits, premiums from beneficiaries and general revenues. The series for Reformed Medicare Spending includes both the effect of lower total spending on Medicare-covered services due to the incentives produced by the rising total deductibles, as well as the spending that will be funded by retirees' HIRAs. At first, the reform's effects are modest, but as an increasing number of retirees have annuity payments from their HIRAs, the effects on total spending grow.

Given that the HIRA reform requires contributions from workers equal to 4 percent of their earnings, these contributions are added to the Reformed Medicare Spending Series to arrive at the final series reflecting the total reform costs. Comparing this series to the Current Medicare series shows the timing of the costs for the two alternatives.

Upper-Bound Estimate of Medicare Spending (Method 1). As seen in Figure IIa, until 2048 the reform is more expensive than continuing the current arrangement. Thereafter the reform is less expensive. In 2050, Reformed Medicare spending is 79 percent of Current Medicare and by 2080 it is 76 percent. By 2080, the total reform costs, including contributions to HIRAs, are 91 percent of what Current Medicare would cost.

Lower-Bound Estimate of Medicare Spending (Method 2). Figure IIb presents the estimates when Method 2 is used to identify the effects of the higher deductible on health care spending, the total costs of the reformed program are less than Current Medicare beginning in 2032. Under Method 2 assumptions, reformed Medicare spending is 68 percent of Current Medicare in 2050 and by 2080 it drops to 66 percent. Total costs for the reformed system are 88 percent of the current system's costs in 2050 and 81 percent by 2080.

“The RAND health experiment showed that modest deductibles reduced health care spending without affecting health outcomes.”

The two methods of accounting for the deductibles' effects provide upper- and lower-bound estimates of the cost of the reform due to demand-side effects only. In either case, the reform is less expensive than the current arrangement in the long run. 19 If supply-side effects were included the change would be more dramatic. As Amy Finkelstein has shown, the introduction of Medicare caused dramatic supply-side effects, such as the entry of new hospitals into the market and the adoption of new, more expensive practice styles. 20 Finkelstein estimates that the market-wide spread in third-party payments can explain half of the growth in per capita spending from 1950 to 1990, a much larger estimate than those previously made. Clearly, greater cost sharing due to the HIRA annuities and base deductibles will not only affect the level of spending, but also the spending growth rate.

[page]The HIRA annuity estimates thus far have been based on the assumption that the real rate of return earned on HIRA investments is 2.9 percent during both the accumulation and decumulation phases of the insurance. The annuities as well as the effects on total Medicare spending were also calculated using a real return of 5.2 percent (the long-run average real return on a 60/40 stock/bond portfolio) for the accumulation phase and 2.9 percent for the decumulation phase.21

“The accounts of younger average-income workers will fund 29 percent to 59 percent of projected spending on Medicare-covered services at age 75.”

Deductibles as Percentages of Spending. Table I summarizes the size of the base deductibles, HIRA annuities and their combination, relative to average spending at age 75 for the three birth years previously depicted and the two rates of return. Because of the short time period that people can accumulate funds in their HIRAs, the effects of the two different rates of return on total deductibles for members of the 1950 birth year are similar. However, workers born in 1970, who are 37 in 2007, have 28 years to accumulate funds in their HIRAs. Those born in 1990 have their entire work lives to contribute.

The table's first panel indicates the base deductibles as shares of Medicare-covered services.22 Recall that the base deductible of $2,500 in 2007 is indexed to the growth in per capita Medicare spending. As a result, its size relative to average spending at age 75 for each cohort is quite similar through time. The base deductible is 16.2 percent of average spending at age 75 for workers born in 1950 and is 17.5 percent for retirees born in 1970 and 1990.

“Reformed Medicare will spend less than the current system beginning in 2048 (Method 1) or as soon as 2032 (Method 2).”

The next panel reports the HIRA annuities as a percentage of Medicare spending on covered services at age 75 for each birth year and for the two rate of return assumptions. This panel illustrates how time to retirement age and rates of return affect the degree to which the HIRA annuities can replace projected spending. Workers with medium earnings who were born in 1950, and who have less time remaining in the labor force before they retire will be able to fund annuities equal to 5.0 percent to 5.6 percent of their projected spending when they are 75 years old — depending on the rate of return assumption. However, the HIRA annuities that today's medium earning young workers can fund through a lifetime of contributions are equal to 28.6 percent to 59.3 percent of projected spending when they are 75 years old. As this panel also indicates, the HIRA annuities are less than the base deductible for older workers, about the same size as the base deductibles for workers born in 1970 and much higher for the youngest workers under the most conservative rate of return assumption.

“HIRAs could earn 5.2 percent, the average long-run return on a stock-and-bond portfolio during the accumulation period.”

The last panel reports the total deductibles. The higher rate of return produces a total deductible equal to about 43 percent of average spending at age 75 for the 1970 birth year rather than the 35 percent deductible with the lower real rate of return. Further, medium earners among today's 17 year olds will accumulate enough in their HIRAs to produce total deductibles equal to almost 77 percent of spending on Medicare-covered services when they are 75 years old if the higher rate of return assumption is used. With the 2.9 percent return assumption, this group's total deductible will equal 46 percent of projected spending when they are 75.

Figures IIIa-IIIc summarize the total deductibles as percentages of Medicare-covered services for all ages for the three sample birth years using the alternative accumulation phase rate of return.

“High-wage workers would pay for 95 percent of their retirement health care costs.”

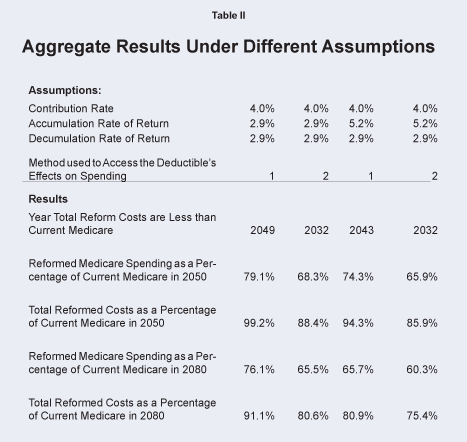

Aggregate Results under Alternate Rate-of-Return Assumptions. Table II compares the aggregate estimates under the two alternative rates of return. The higher total deductibles resulting from the higher rate of return assumption will induce greater spending responses. Table II compares the alternative results in terms of the crossover year, and the relative costs in 2050 and 2080. The first two columns summarize the estimates underlying Figures IVa and IVb. The last two columns summarize the estimates when the higher rate of return is used for the accumulation phase of the insurance. Figures IVa and IVb depict the annual cost estimates using the two methods for determining the deductibles' effects on total spending.

Using Method 1 to account for the effects of the total deductible, combined with the higher rate of return, produces 2043 as the estimated year when the cost of the reformed system falls below that of current Medicare. The crossover year is 2049 when the 2.9 percent return is used.

Using Method 2 produces a crossover year of 2032 under both real return assumptions. The long-run effects, however, show that the higher discount rate and resulting higher deductibles further reduce the projected total spending with the HIRA reform. By 2080, reformed Medicare spending is 40 percent less than is currently projected.

“The cost of reformed Medicare spending will be 20 percent to 35 percent less than the current system by 2050.”

This study has outlined a comprehensive reform that addresses Medicare's costs and revenues. The objectives of the reform are to address the unequal burden the current financing arrangement places on different generations and to address the growth in projected spending by increasing cost sharing. Partial prepayment through HIRAs requires the current generation to pay some of the costs they will create for future workers if the program is left unchanged. The HIRAs will produce increasing cost sharing as more and more individuals retire after contributing to their HIRA accounts for more and more years.

“The total burden of financing the reformed program would be 10 percent to 25 percent less than under the current system by 2080.”

Given that the HIRA contribution rates are the same for all workers, higher income workers will naturally have higher annuity payments and will face higher deductibles. Thus, the cost sharing burden will be greater for higher income workers. These workers will prepay more of their retirement health care than lower income workers of the same age. Differential Medicare coverage tied to retirees' incomes is not a new concept. As mentioned earlier, Medicare Part B premiums are already means tested, albeit the income thresholds as currently defined will only affect the premiums paid by retirees with relatively high incomes. Means testing of Medicare has been discussed by economist Mark Pauly and others. 23 Also, one of the policy implications from the RAND experiment was the possibility of income-related deductibles. 24 Finally, Alan Greenspan has suggested that higher income retirees may well be required to fund most of their retirement health care in the future. 25

“The reform plan would maintain the progressivity of the current system while reducing costs to taxpayers.”

The HIRA reform formalizes the mechanism by which future retirees fund part of their retirement health care, with higher income retirees funding greater shares of their consumption in the two ways outlined. This reform gives all retirees much greater control over their health care spending. By 2030, retirees will become a 70-million-strong health care consumer watchdog group. The reform also avoids the alternative of bureaucratic rationing of health care and will allow subsequent generations to spend less of their incomes supporting federal elderly entitlement programs than under the current financing arrangement.

NOTE: Nothing written here should be construed as necessarily reflecting the views of the National Center for Policy Analysis or as an attempt to aid or hinder the passage of any bill before Congress.

[page]- This is pursuant to a provision of the 2003 Medicare Modernization Act.

- The tax revenues credited to Medicare are a function of the expected income taxes on Social Security benefits, so they rise with the size of Social Security benefit income.

- This is referred to in the Medicare Trustees Report as the Medicare Part A actuarial deficit.

- Assumes that federal taxes other than the social insurance revenues remain at their historical share of GDP.

- Deposits to HIRAs will be made much in the same way as deposits are made to retirement savings accounts. The first set of the estimates presented later in the paper are based on the conservative assumption that the accounts earn a real return of 2.9 percent.

- Mechanically, funds in the HIRAs of deceased participants will be distributed at the close of each year across all survivors in the decedents' age cohort in proportion to their account values.

- The structure of the transition up to the point in time when all retirees have contributed to HIRAs for their entire work lives will affect the costs and benefits of the reform during the intervening years.

- The ultimate effect of the HIRA contribution on participants' consumption depends on the beliefs current participants have about the level and form of reductions in benefits that can or will be enacted by Congress to address the pending Medicare shortfalls. To the extent that individuals base their consumption behavior on the projected effect of the reform, the 4 percent contribution coupled with the reform may result in offsetting consumer saving so that income available for consumption actually rises even as after-tax income falls.

- Rettenmaier and Saving, The Diagnosis and Treatment of Medicare (Washington, D.C.: AEI Press, 2007), page 126.

- This is the rate used by the actuaries in producing the 2007 Medicare and Social Security Trustees report.

- The RAND simulation results on which the two methods are based are from Table 3.4, page 19 and Table G.2, pages 104-105, in Willard G. Manning et al., “Health Insurance and the Demand for Medical Care,” February 1988, RAND, R-3476-HHS.

- Assuming the low-income retiree is not eligible for Medicaid. Other federal health care programs, particularly Medicaid, pay for health care spending on behalf of low-income retirees by supplementing Medicare and paying for long-term care for eligible beneficiaries. Also, Medicare as currently structured may ultimately treat beneficiaries differently based on their incomes. Mark McClellan and Jonathan Skinner suggest that though high income workers pay more payroll taxes and income taxes, they also have higher use of physician and ambulatory services and higher life expectancies which lead to higher lifetime Medicare spending. Before the taxable maximum was removed on earnings subject to the Medicare payroll tax, intergenerational transfers from low-income to high-income workers resulted. Once the taxable maximum was removed, McClellan and Skinner found that redistribution from high- to low-income households resulted for later birth years. When they adjusted for the insurance value of Medicare, they found further redistribution from high- to low-income households. See Mark McClellan and Jonathan Skinner, “The Incidence of Medicare,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 6013, April 1997.

- In 2007, Part B required income-related premiums for individuals and couples with $80,000 and $160,000 or more in annual income, respectively. The thresholds will rise with the Consumer Price Index (CPI). The higher a retiree's income the higher his or her premium will be relative to the base standard premium. By 2009 individuals with incomes of $200,000, adjusted for inflation, will have premiums 3.2 times the standard premium. This group of retirees will thus pay a premium equal to 80 percent of the average cost per retiree and as a result may opt not to participate in Part B.

- The simulations use data from the April 2007 Medicare Trustees Report, the 2007 Social Security Administration's population estimates, cohort life tables, and projected wage profiles for very low, low, medium and high lifetime wage earners. Medicare spending by age and birth year is projected based on data from the Continuous Medicare History Sample. These projections are used to allocate total annual spending on aged beneficiaries to specific birth years.

- Medicare-covered services include Medicare's own reimbursements as well as out-of-pocket spending and any third-party payments. The age-spending profiles are derived from projections of spending by age in future years and are benchmarked relative to the aggregate projections from the 2007 Medicare Trustees Report. These are the estimated profiles that would exist before determining the effects of the higher cost sharing on spending. The percentages presented thus illustrate the size of the private payments relative to average anticipated age-specific spending on covered services under Medicare's current structure.

- Spending in the year in which an individual turns 65 includes on average one-half of a year's spending given the timing of eligibility based on new entrants' birthdays. For this reason, spending in the year beneficiaries turn 65 is excluded from the graph.

- The average inflation-adjusted age spending profiles rise from the age of 66 until the early 90s for each birth year and then decline at higher ages. The ratio of total cost sharing to average spending by age has the shape depicted in the figure because the numerator of the ratio is growing in real dollars due to the rising base deductible that is added to a fixed real dollar annuity from the HIRA but the total cost sharing does not rise as rapidly as the age spending profile until is peaks at about the age of 92.

- Though Parts A, B and D would be combined into one health insurance package with this reform, it is assumed that beneficiaries would continue to participate in funding some of the cost of the program as they do now through their Parts B and D premium payments. These payments currently account for 11 percent of the total cost of the program. With the HIRA reform, beneficiaries could continue to fund this percentage of the program's reformed costs through premium payments. Whether the premiums are the same across all income classes, or are adjusted for lifetime or current income, is an additional policy consideration.

- In addition to the demand-side effects of higher cost sharing, there will also be significant supply-side effects. Suppliers of health care services will face increased price competition for the services they supply. The increased price competition will affect services consumed by beneficiaries both below and above the total cost-sharing cap given that the component services used in treating low-expenditure cases overlap significantly with cases which exceed the cost-sharing threshold.

- Amy Finkelstein, “The Aggregate Effects of Health Insurance: Evidence from the Introduction of Medicare,” Quarterly Journal of Economics , February 2007, pages 1-38.

- The higher rate-of-return assumption brings up the concern that different cohorts may have quite different annuities even if they had similar earnings profiles simply because of market volatility. This concern can be addressed in several ways. One would be to require the insurance providers to smooth some of this risk through time by staggering the timing of annuitization of each new set of retirees, or by requiring them to contribute to a reinsurance fund. These provisions would reduce the rate of return closer to the government borrowing rate. However, even in the case in which annuities are allowed to vary with market conditions at the time of annuitization, some of the concerns that plague personal retirement account proposals are not present here, given that for most retirees Medicare will continue to be the ultimate insurer for catastrophic events. Higher annuities for workers who retire during a stock market boom would produce higher cost sharing requirements. Similarly, workers who retire in a down market would have smaller cost sharing requirements.

- Again, the projected spending on covered services is derived from the 2007 Trustees Reports and as such does not reflect the reduction in spending that would result from the higher cost sharing. The projected spending under the current program's structure is simply used to provide a convenient point of comparison.

- Mark V. Pauly, “Should Medicare Be Less Generous to High-Income Beneficiaries?” in Andrew J. Rettenmaier and Thomas R. Saving, eds., Medicare Reform: Issues and Answers (University of Chicago Press, 1999).

- Joseph P. Newhouse, Free for All? (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1993).

- Alan Greenspan, The Age of Turbulence: Adventures in a New World (New York City: Penguin, 2007).

Dr. Andrew J. Rettenmaier is the Executive Associate Director at the Private Enterprise Research Center at Texas A&M University. His primary research areas are labor economics and public policy economics with an emphasis on Medicare and Social Security. Dr. Rettenmaier and the Center's Director, Thomas R. Saving, presented their Medicare reform proposal to U.S. Senate Subcommittees and to the National Bipartisan Commission on the Future of Medicare. Their proposal has also been featured in the Wall Street Journal, New England Journal of Medicine, Houston Chronicle and Dallas Morning News . Dr. Rettenmaier is the co-principal investigator on several research grants and also serves as the editor of the Center's two newsletters, PERCspectives on Policy and PERCspectives . He is coauthor of a book on Medicare, The Economics of Medicare Reform (Kalamazoo, Mich.: W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, 2000) and an editor of Medicare Reform: Issues and Answers (University of Chicago Press, 1999). He is also coauthor of Diagnosis and Treatment of Medicare (Washington, D.C.: American Enterprise Institute Press, 2007). Dr. Rettenmaier is a senior fellow with the National Center for Policy Analysis.

Dr. Thomas R. Saving is the Director of the Private Enterprise Research Center at Texas A&M University. A University Distinguished Professor of Economics at Texas A&M, he also holds the Jeff Montgomery Professorship in Economics. Dr. Saving is a trustee of the Social Security and Medicare Trust Funds. His research has covered the areas of antitrust and monetary economics, health economics, the theory of the banking firm and the general theory of the firm and markets. He has served as a referee, or as a member of the editorial board, of several major U.S. economics journals and is currently an editor of Economic Inquiry . Dr. Saving has authored many articles and two influential books on monetary theory. He has been president of both the Western Economics Association and the Southern Economics Association. After receiving his Ph.D. in economics in 1960 from the University of Chicago, Dr. Saving served on the faculties of the University of Washington and Michigan State University, moving to Texas A&M in 1968. Dr. Saving served as chairman of the Department of Economics at Texas A&M from 1985-1991. Dr. Saving is a senior fellow with the National Center for Policy Analysis.